Along with artist Callum Morton, Kosloff Architecture dressed up this Monash University research building in a beautiful—and cost-saving—second skin.

Artist Callum Morton’s funnel design makes for quite an entrance. [Photo: Derek Swalwell]

PROJECT: 18 Innovation Walk LOCATION: Clayton, Australia COMPLETION: 2017 ARCHITECT: Kosloff Architecture ENGINEERS: Rush Wright Associates LANDSCAPE ARCHITECT: Rush Wright Associates ARTISTS: Callum Morton, Monash Art Projects FACADE MANUFACTURER: Fabmetal PAINTWORK: Stylerod Panels

In the late 1950s and 1960s, the Monash University Clayton campus in Clayton, Australia, near Melbourne, expanded rapidly through the construction of primarily modernist architecture. For half a century, an eight-story brick-clad building, originally designed in 1969 by modernist pioneers Stephenson & Turner, has stood at 18 Innovation Walk. Today, that building is nearly unrecognizable.

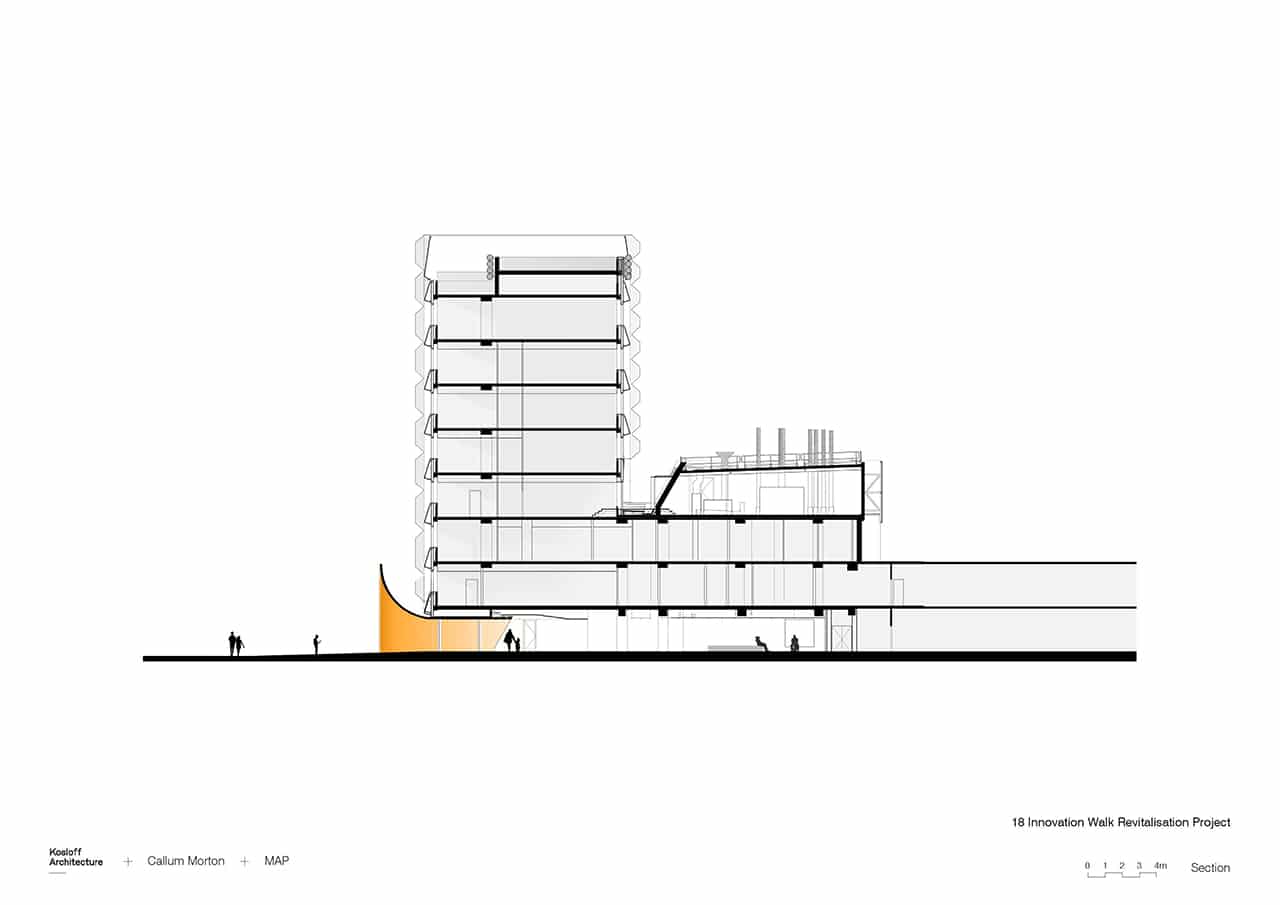

A new facade gives the appearance of a curtain draped over custom-colored glazed brick—left exposed where the facade lifts at the pedestrian level to reveal just a glimpse. Glass-reinforced concrete shells with differentiating depths give the building its form and shading, creating a dynamic appearance of a wall that constricts and expands in motion. A steel, trumpet-like funnel welcomes guests at the building’s entrance—nearly 30 feet wide, 20 feet tall, and fading from warm orange to bright yellow.

The new exterior’s successes go beyond the aesthetic, as the shading system cuts down on solar gain by a third. [Photo: Derek Swalwell]

Originally a response to a deteriorating brick exterior, the re-skinning process of 18 Innovation Walk evolved as the entire building saw substantial upgrades in services infrastructure and improvements in environmental performance, while also supporting a strategy for public art integration. The project was a collaborative effort between Kosloff Architecture, artist Callum Morton, and the Monash Art Projects, with landscape design by Rush Wright Associates.

“What is unique about the design of this building is that, from an essentially utilitarian and pragmatic brief requirement of replacing an existing failing facade evolved such a unique and beautiful outcome,” says Julian Kosloff, cofounder, along with Stephanie Bullock, of Kosloff Architecture.

Not only was the team tasked with designing a skin that the building’s existing structure could support, they also removed and constructed an exterior without displacing any occupants—all classrooms, offices, and laboratories remained in use. Kosloff says this was incredibly challenging, though critical for a biology building that houses experiments that are years in progress.

Adding to an already ambitious undertaking, the team chose to prioritize updating the building’s environmental performance and, in particular, address the building’s problematic east-west orientation. Through a process of intensive modeling, a shading system was designed as part of the the new facade, which reduces solar gain to the building by 30%. Kosloff says the design process of such a complex collaborative effort involved a constant exchange between artist and architect—working together to upgrade an existing structure to support both current and future research and teaching needs.

“The design of this building supports our belief that the practice of architecture needs to be fundamentally driven by our responsibility to the environment and that adaptive reuse, rather than to discard, is at the forefront of this approach,” Kosloff says.

Remarkably. the project team constructed the new exterior without displacing any of the research building’s users, even temporarily. [Photo: Derek Swalwell]

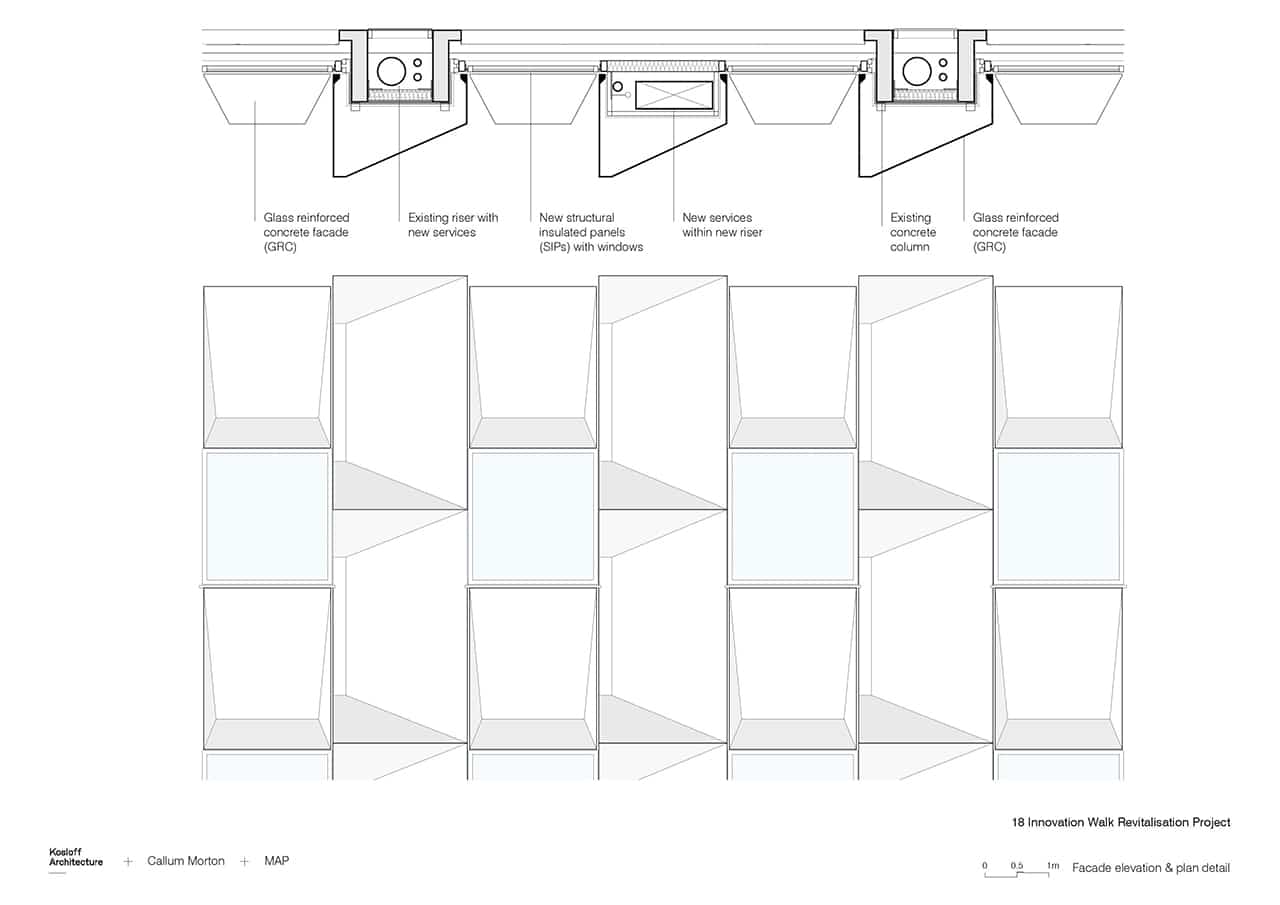

Facade Construction

Keeping with efforts to work around a bustling university environment, the 18 Innovation Walk team conceived a construction sequence and installation methodology that would allow them to keep the entire original brick facade and windows in place while the new exterior was built over it. After the new exterior was finished, the original windows and walls were demolished from the inside, leaving the upgraded, high-performing wall behind.

Panel Design

The diverse three-dimensionality of the white panels that create the building’s new skin come together to create a fluid, wave-like design—a nod to artist Callum Morton’s sculpture work. Each panel is made of glass fiber-reinforced concrete and molded as a shell, around a half-inch thick. The panels are hollow, and new mechanical and hydraulic equipment are hidden inside in an effort to future-proof the building, by upgrading its services infrastructure.

[Drawing: Courtesy of Kosloff Architects]

[Drawing: Courtesy of Kosloff Architects]

Building Insulation

Because of the east-west orientation of the existing structure, much of the building’s facade is exposed to direct sunlight. The extended design team, including services engineers and environmental consultants, collaborated intensively to develop a fully integrated solution to this challenge. The original, single-glazed windows were replaced with high-performance double-glazed windows in conjunction with a new highly insulated facade with integrated shading. The new facade is fully shaded between 10:30am and 2pm during the summer months—avoiding peak midday sun. The external wall’s R-rating (in which a higher R-value means greater insulation effectiveness) has improved from 0.5R to 3.5R as a result. Overall, the new design led to a 24% improvement in thermal performance.

Money Saved

By choosing to upgrade the existing building and replace the deteriorating facade, the university saved a significant amount of money compared to the price of constructing a new structure. Since 18 Innovation Walk functions as the university’s biology department, the plants and animals that it houses in research laboratories would have needed to be relocated. Because many of these projects have been ongoing for years, the potential cost of lost research data was high. By simply avoiding disrupting experiments, the university estimates they saved close to $2 million.