When the Center for Sustainable Landscapes, or CSL, officially opened to the public this past spring, it was one of the largest buildings designed to achieve Living Building status in the United States. The tri-level, 24,350-square-foot garden, education, administrative, and research center at the historic Phipps Conservatory and Botanical Gardens in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, should also earn LEED Platinum and SITES certifications. Although construction on the CSL began in 2010, its idea was conceived five years earlier in a conversation that took place 2,500 miles away.

Richard Piacentini, Phipps’s executive director, was at the Greenbuild International Conference and Expo in Denver, Colorado, in November 2006. The conservatory had recently completed construction on its 12,000-square-foot Tropical Forest Conservatory, a passively cooled greenhouse and changing exhibit space with an open-roof system and dozens of other cutting-edge green technologies. At the time, the Phipps team was “really trying to understand how the environment interacts with buildings,” Piacentini says, “and, more importantly, how buildings interact with the environment.”

Executive director Richard Piacentini visits the building site of Phipps Conservatory’s new Center for Sustainable Landscapes. Photo: Alexander Denmarsh Photography

The Welcome Center at Phipps Conservatory in Pittsburgh, PA, is already LEED Silver certified. Photo: Alexander Denmarsh Photography.

Attending the conference was the creator of the EPA’s Energy Star program logo. Piacentini told him a few of his ideas for Phipps’s next project, which included implementing ways to use conservatory-campus waste to create methane for fuel cells as well as utilizing water stored in underground cisterns to act as a thermal sink for heating and cooling purposes.

“I showed him the diagram for what we were planning for our next building,” Piacentini recalls of that fateful day. “We didn’t know it at the time, [but] he said what we had was the diagram for a ‘living building.’”

The day before this conversation, Jason McLennan, the new CEO of the Cascadia Green Building Council, had introduced the Living Building Challenge to all 12,000 conference attendees during a keynote address. “I knew I had to meet McLennan next,” Piacentini says. “As we got to talking, sure enough, it was clear we were already in gear for this new challenge.”

McLennan and Bob Berkebile—one-time architectural partners at BNIM—had created the Living Building Challenge, or LBC, to challenge builders to utilize and implement innovative, sustainable tools for new and renovated buildings and landscapes. It challenges builders with 20 imperatives broken into seven performance areas, similar to LEED. The LBC, however, is far more stringent; imperatives include growth limits, net-zero water and energy, appropriate sourcing, conservation and reuse, rights to nature, and other demanding considerations.

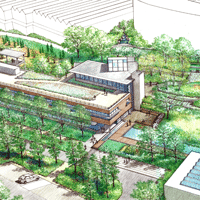

A rendering of the Center for Sustainable Landscapes, which is expected to reach LEED Platinum and Living Building Challenge status. Rendering: Andropogon Associates

The design for the Center for Sustainable Landscapes concentrated on the surrounding environment, including water-conservation features and constructed wetlands.

In January 2007, the Phipps Conservatory accepted the Living Building Challenge for its next building. In the design phase, which was energized by this new challenge, “we got really excited by the possibility of creating one of the greenest buildings in the world,” Piacentini says. “We didn’t just want this to be about Phipps—we wanted to involve and showcase all of our local talent.”

As Phipps formed its team, which eventually included partners from Carnegie Mellon University, University of Pittsburgh, Turner Construction, The Design Alliance Architects, and dozens of others, Piacentini says he “became convinced that integrated design was the only way to truly create a high-performance green building.” Integrated design demands that all project members have a shared vision for sustainability and project completion. “The proposals [stated] our requirement that everyone on the team follow a facilitated integrated-design process,” he adds.

John Boecker, from 7group, facilitated the integrated-design process, and Piacentini says they were able to assemble a strong, like-minded team to begin building the CSL.

Because it is so integrated with the natural environs, Piacentini says the new building’s landscape, by Civil & Environmental Consultants and Andropogon, plays the most important role when it comes to efficiency. The constructed wetlands, storm-water-management systems, shading, and rooftop permaculture-demonstration garden all serve to integrate the building with the surrounding environment.

One challenge was treating water, an LBC requirement. Project engineers designed a filtration system that will divert sink and toilet water to a settling tank and constructed a wetland where plants will clean the water before it is passed to a sand filter and a UV sterilizing unit. From there, it will be recirculated to flush the toilets again.

In order to pass regulation, however, the CSL needed to dispose of 200 gallons of purified water a day in excess of what was needed to flush the toilets (regulations would not allow it to infiltrate the ground). To get rid of this water, Phipps is utilizing the Epiphany Solar Water System, a solar-heated water-distillation system created by Tom Joseph and Henry Wandrie. “It’s an amazing system,” Piacentini says. “It creates pure distilled water soft enough to water our orchids, which are sensitive to chemicals in municipal water.”

Sometimes, a conversation is all it takes. By employing innovative green solutions, working with regional architects and engineers, and maintaining public accessibility, the CSL will be an example of living building potential. “America has a history of innovation,” Piacentini says. “The Living Building Challenge shows how, with limited resources, we can improve our standards of living while bettering our relationship with the environment.”