This article is part of gb&d‘s Green Typologies series, Places of Worship: Contemporary Religious Design in America.

Originally derived from the Greek katholikos, the word catholic means universal, or pertinent to all. If modern architecture is defined by abstraction, the Cathedral of Christ the Light in Oakland, California, designed by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM), is abstract in the most catholic sense of the term. The 250,000-square-foot church complex, with its distinguishable 136-foot-tall, glass-clad cathedral, overlooks the northwestern arm of Oakland’s scenic Lake Merritt. It sets an expressive foreground for the church, which forms the communal center for more than 500,000 Catholics in Alameda and Contra Costa counties.

Traditionally, Catholic architectural history is as stately as it is iconic, not only for the way it reflects the strength of the Catholic theological tradition but also for its assertive and at times authoritarian assumptions. Although customarily reverential in its grandeur, Catholic architecture is often firmly rooted in its European and Gothic genealogy, and—perhaps at the price of being a 1,500-year-old legacy—it frequently fails in its aesthetic expression to abide by the apostle Paul’s injunction to “be all things to all people.”

Through its innovative use of site development, urban planning, and spatial orientation, the Cathedral of Christ the Light draws its abstractions both from universal religious experience and the Catholic liturgy to create a truly comprehensive program. In addition to the cathedral, the campus includes a mausoleum, parish hall, conference center, a garden, diocese offices, archive and library, rectory with housing for 12 clergy, a cathedral store, a parking structure, a free legal clinic, and a free health clinic. However, as Craig Hartman, design partner at SOM and designer of Christ the Light, says, “We made all of these dependencies secondary to the cathedral itself, which is slightly turned on the orthogonal campus plan so that its long axis engages the long axis of the lake, while the dependencies surrounding the cathedral engage the surrounding urban elements.”

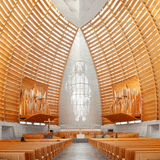

The 1,350-seat cathedral is symbolically oriented to mirror its penitent function by being situated in the city and positioned to overlook the lake, and for Hartman, it was this type of religious awe that inspired the architecture. “We were trying to discover what constitutes the spiritual quality of a physical space,” Hartman says. “The essence of sacred space isn’t luxurious materials and iconography, or even architecture. To stand within a majestic grove of sequoias with delicate light filtering through the overhead canopies is to experience spiritual space. It was that ineffable, poetic quality of light that can ennoble even the most modest of materials that we were searching for in the design of the cathedral.”

“It was that ineffable, poetic quality of light that can ennoble even the most modest of materials that we were searching for in the design of the cathedral,” says SOM’s Craig Hartman of the project.

With this model in mind, the cathedral begins with 15-foot-high concrete walls, formed with fly ash, a recycled material, and slag. In addition to forming a bold and sculptural backdrop, the walls function to create thermal mass while also performing an integral role in the structure’s thermal inertia system. “This is a passive system,” Hartman says. “We’ve cut small grills in the floor under the pews, and we allow cool air harvested overnight to come into the cathedral in the morning, and it remains there even as the building heats during the day. During the winter, we use hot water in the floor slabs to create radiant heating, just like the Romans did in the first millennium.”

The wooden walls are made from Douglas fir pieces, sourced from renewable forests, that are ribbed and louvered together as they ascend to the oval ceiling, which is made of faceted aluminum and diffuses light transferred through the glass oculus on the cathedral’s roof. The oculus takes the form of a gigantic Vesica Piscis, a shape formed at the intersection of two circles that share the same radius.

The cathedral’s interior volume and exterior shape are both derived from rigorous geometries. The interior wooden structure comprises two spherical segments while its pellucid exterior skin is formed by two conical segments of fritted glass, translucent laminate glass, and clear low-E glass. White aluminum mullions, set on a 10-by-5-foot grid pattern, frame the glass. “The fritting has a geometric design pattern to give it a very organic quality,” Hartman says. “And given this tapestry of translucent and opaque patterned glass, the building image changes throughout the day; at times it appears very solid and at other times becomes very ephemeral and luminous.”

The interior and exterior forms meet as concentric circular segments atop the concrete base. The cathedral’s lightweight, high-strength structure was made by lacing the two shapes together with compressive struts of wood and delicate tensile rods of steel.

Further into the realm of abstraction, behind the altar on the cathedral interior is a 58-foot-high icon of Christ drawn from a Romanesque sculptural relief circa AD 1140 located on the west façade of the Chartres Cathedral in France. The ancient bas-relief sculpture is recast as an aluminum veil, with the image of Christ rendered in light passing through 94,000 laser-cut perforations.

In addition to the thermal inertia and comprehensive daylighting systems, longevity was an essential aspect for the construction of the cathedral. The former home of the Catholic Diocese of Oakland was at the Cathedral of Saint Francis de Sales, which was irreparably damaged in 1989’s Loma Prieta earthquake. Christ the Light is set on a friction-pendulum, seismic base-isolation system. The elasticity of the wood will also serve to offset ground tremors, so although the cathedral is lightweight, it is also strong. “The diocese wants this building to last 300 years,” Hartman says. “Part of making sustainability viable in California is making buildings withstand earthquakes, which is why we’ve base-isolated the building.”

Since the cathedral was completed in 2008, it has not only affected change by creating a multiuse center for greater Oakland’s Catholic community, but through its publically accessible community programs and services, it has fostered a sense of universality—or Catholicism—that has brought new life to Oakland’s Uptown area.

“In terms of its function, but also its technologies, this is a building very much made for this time and this place,” Hartman says. “Oakland is a diverse, multicultural city, so the intention was to create a building form that was welcoming to all of these cultures while also specifically honoring the Catholic liturgy.”

This article is part of gb&d‘s Green Typologies series, which in each issue explores a single type of building. For more of our most recent collection, Places of Worship: Contemporary Religious Design in America, choose from the list below.

• Prayer Pavilion of Light, DeBartolo Architects

• Green Mosque Proposal, Faith in Place

• St. Nicholas Eastern Orthodox Church, Marlon Blackwell Architect

• Westchester Reform Temple, Rogers Marvel Architects