Catch basins aren’t known for their beauty. They serve an important function, to be sure—collecting stormwater run-off so it can be detained, filtered, and released safely into the subsurface hydrological system or watershed. But their depressed intake systems make them difficult to incorporate architecturally, particularly in high-traffic pedestrian areas, such as crosswalks, where steeply sloped surfaces can be difficult to navigate.

Then there are the aesthetic concerns: the landscape architect whose linear, clean-lined hardscape is sullied by the grated cast iron maw of a water inlet; the designer who wants to install pavers but can’t because such a flat, ungraded surface won’t divert enough run-off.

Finding a solution to these competing concerns—draining stormwater, while retaining an even, walkable surface—is essentially why Brickslot was designed, says Ben Aulick, the southeast region specifications manager for ACO.

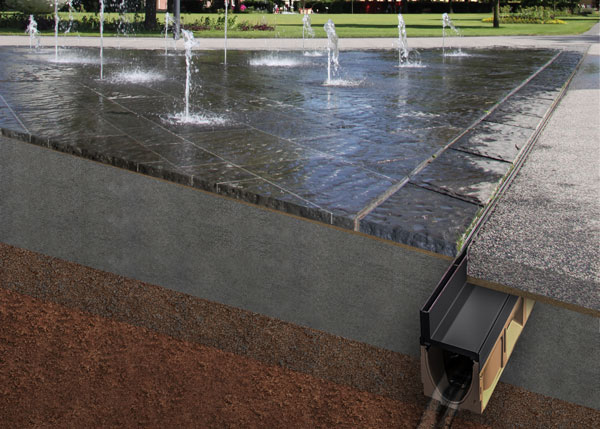

The ACO Brickslot L-shaped slotted intake system, nearly invisible to the eye, rests atop a four-inch-wide galvanized or stainless steel trench, Aulick says, allowing brick or stone pavers to be installed in a linear fashion along walkways and courtyards. Water slips through the grated slots, which take the place of paving joints, and is funneled into a catch basin where it is detained and filtered before being released to an outlet point.

Brickslot is the first step of a much larger stormwater system chain, and, in some ways, the goal of the product is not to see it at all. “Brickslot was really designed to help engineers and architects work together more efficiently to develop an aesthetically pleasing stormwater system that is virtually invisible within a hardscape,” Aulick says.

The depressed intake systems of catch basins make them difficult to incorporate architecturally, but the ACO Brickslot L-shaped intake system helps to alleviate competing concerns over aesthetics and functionality. PHOTO: COURTESY OF ACO POLYMER PRODUCTS, INC.

As an example, he points to the design and installation of a gracious, boulevard-like walkway of brick, pavers, and concrete that forms the pedestrian entrance to a CVS at the corner of Augusta St. and Faris Rd. in Greenville, South Carolina. A project team that included McLeod Landscape Architects, Little Diversified Architectural Consulting, and Spell Construction Inc. completed the seven-month project in November of last year.

And here’s how ACO got involved: Parks McLeod, of McLeod Landscape Architects, was attending the 2013 American Society of Landscape Architects trade show in Asheville, North Carolina, when he bumped into Aulick. He shared his plans for the front entrance, which delineates the main road from the building and is inlaid with brick pavers from end to end. “Parks saw an immediate need [for Brickslot]. He had this beautiful hardscape and he didn’t want to hurt it,” Aulick says.

The issue, of course, was stormwater drainage. Because the new walkway would reduce water absorption into the ground, Aulick says, the difference needed to be accounted for in the drainage system. Greenville’s stormwater design criteria, specified in the city’s Design and Specification Manual, are particularly stringent. With the adoption of the Land Management Ordinance in January 2008 and a new stormwater ordinance in February that same year, the city retains tight control over how development will affect system sizing, flow rates, and system depth, alignment, and materials. In this way, it adheres more closely to the regulatory environment of larger cities, such as New York, than small- to mid-market cities, Aulick says. “They’re very advanced and forward thinking in how they handle stormwater retention, which is a good thing. We’ve done a lot of projects in that market; they have landscape architects on the city’s staff and have placed a special interest in making the city’s parks and streetscapes attractive,” Aulick says.

But Greenville is not alone in their progressive policies. Across the country, according to Aulick, such requirements are becoming increasingly common: some municipalities mandate that flow rate differences in stormwater run-off before and after development be recovered on-site, either by incorporating water-absorbing landscapes, such as raingardens and bioswales, or by regulating the rate of release of stormwater back into the hydrological system. Others specify a “first flush” rule, holding that water cannot collect on-site after the first major rain following development.

The CVS project is but one of many that use Brickslot. “It’s a very good selling, quality product. We’ve used it at the World Trade Center site in New York City and the Atlanta Braves’ [SunTrust Park] and Falcons’ [Mercedes-Benz Stadium] stadiums in Atlanta,” Aulick says.

RENDERING: COURTESY OF ACO POLYMER PRODUCTS, INC.

Self-described on their website as “the world market leader in drainage technology,” ACO occupies a dominant position in a market that would appear to be growing as development and predicted climate change effects put increasing strain on aging municipal stormwater systems and intensified flooding. The family-owned company, headquartered in Rendsburg/Büdelsdorf, Germany, has a presence in over 40 countries, with a total of 30 production sites on four continents. In addition to Brickslot, ACO manufactures drainage channels, oil and grease separators, backflow stop systems, pumps and pressure-water-tight cellar windows and light shafts. Their tag line reads “ACO. The Future of Drainage.”

Asked what that future looks like, Aulick responded, “We’re a global company on a global scale. We’re on track to exceed a billion dollars in revenue. In the US market, you don’t have a comparison in terms of lineal stormwater drainage. Our global counterparts have been doing sustainable designs a lot longer than in the US, and the evolution of these products and their availability to designers means that efficiency can be built into the design; form and function are getting married in terms of stormwater drainage,” Aulick says.

What’s next? According to Aulick, a new curbside system, already popular in Europe, which is being used by several hotels and resorts in the southern United States and gaining attention. The monolithic system, made of poured polymer concrete and built into curbs, sits above a trench drain and draws water in through an ungrated mouth. He expects to see increased usage in parking islands and at crosswalks near schools. “It won’t take the place of underground piping, but it will use areas of heavy foot traffic, like crosswalks in cities, to release surface water,” Aulick says.

Download a PDF of this story here.

Connect with ACO USA.: Website | Facebook | Twitter | LinkedIn

![]()