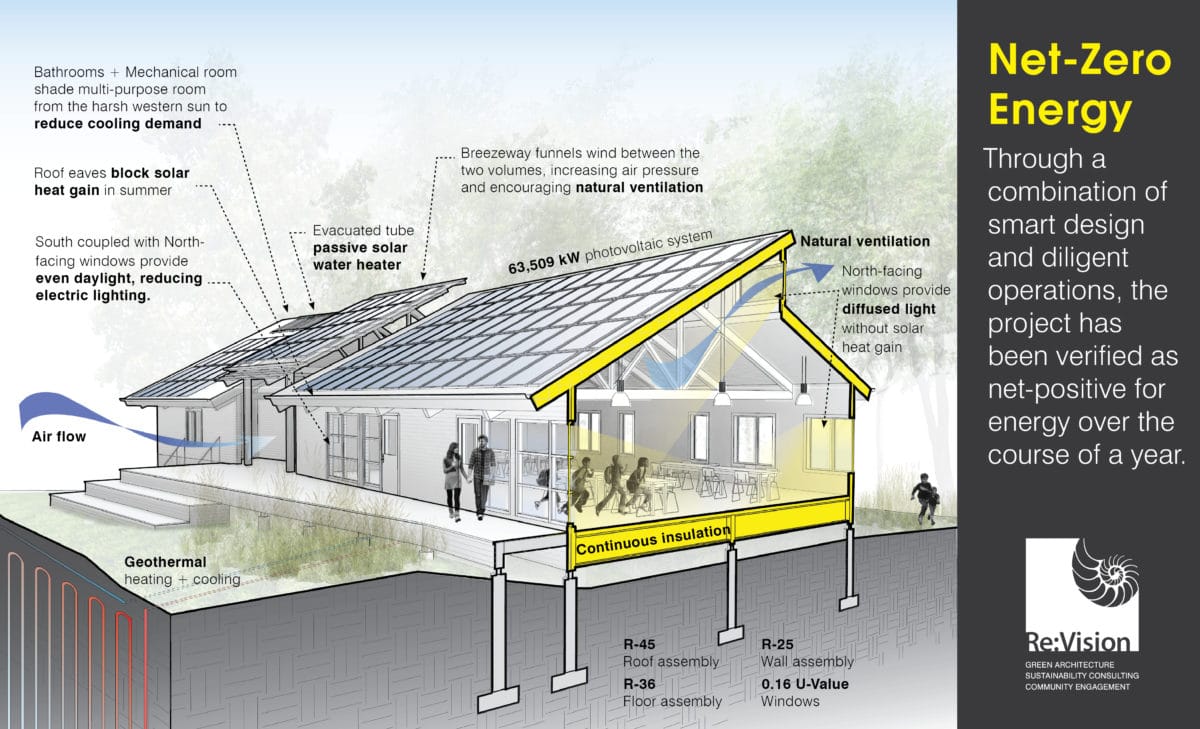

This environmental education center in Maryland is a testament to the Living Building Challenge. [Photo: RE:Vision Architecture]

The nickname for the Morris and Gwendolyn Cafritz Foundation Environmental Center is the Grass Building, and it perfectly captures its spirit. It’s a structure so thoughtfully designed it’s almost as energy-efficient and low impact as the greenery that surrounds it.

The Maryland building is part of an educational farm on the Potomac River Watershed that the Alice Ferguson Foundation used to teach people about the natural world. This new building—which became the 13th in the world to receive full Living Building Challenge certification in June 2017—is an educational facility designed to blur the lines between indoors and out, while still providing shelter as needed. “Part of the intent of the building is to be in the landscape and still have a bathroom to use,” says Scott Kelly, principal-in-charge at Re:Vision, a Philadelphia-based architecture and design studio.

[Photo: Re:Vision Architecture]

Conveniently, that goal aligned neatly with the LBC’s emphasis on biophilia, design that forges a connection between a building’s occupants and the natural world. At the Grass Building, that begins as soon as visitors step foot on the property. The main entrance encourages a pedestrian approach, and visitors are led along a meandering path that essentially leads them on a nature stroll through a grove of trees, over a footbridge, and across some wetlands. When they reach the building and ascend the stairs, crossing between salvaged white oak posts holding photovoltaic panels, they find themselves in a breezeway framing a view of the tree canopy and understory. It’s like a front row seat to the forest. Nature remains omnipresent even when you step indoors, where walls are painted with murals of local wildlife and the width of the structure was carefully considered so no one is ever seated more than 30 feet from a window.

The most challenging part of the project was balancing the LBC’s demand that the project use an ecological water system with local regulations that don’t account for such a thing. The design team envisioned a building that takes advantage of captured rainwater, composting toilets, and a low-energy irrigation system, but were told by county officials that these innovations wouldn’t be permitted. Instead, they’d have to install a conventional septic system. The team pled their case to one official after another, all the way up to the EPA, but they were never able to get the approval they needed to use rainwater as a potable water source. They did have some success, though: After years of lobbying county officials, the project was granted an exception and allowed to install an “experimental” irrigation system that filters water through plant roots and biologically active soil to safely return it to the aquifer. They were also allowed to use composting toilets, which transform human waste into fertilizer.

[Diagram: Re:Vision Architecture]

Those permitting hurdles meant the building took much longer to complete than most projects—11 years from start to finish—but obstacles like those are part of the point of the Living Building Challenge. Every time a new structure is built to meet LBC certifications it’s a win for the environment and the health of that building’s occupants, but it’s still only one building. It’s through the activism of architects and designers who work on those projects that larger systems change to become more eco-friendly. Kelly likens it to the massive changes he’s seen in the industry since LEED first came on the scene more than two decades ago.

“Let me put it like this. The first LEED project we ever did, we called the manufacturer and we asked them to tell us how much recycled material is in the product. They hung up on us,” Kelly says. “At first, these manufacturers were looking at us like we had three heads, but now they get it.”

That same pattern is already playing out with the most famously daunting piece of the Living Building Challenge—the Red List of harmful and polluting chemicals that are banned from every Living Building. Architects tell horror stories about spending months trying to learn the components of a piece of plywood, but as transparency in manufacturing catches on, it’s getting easier. That’s especially true because of the Declare Label, the Living Future Institute’s “nutrition label for buildings,” a database that includes a breakdown of all the components of a material for any vendors willing to submit themselves to that kind of transparency. “The advocacy work we’re doing,” Kelly says. “It’s having a ripple effect.”