[Rendering: Courtesy of NYC Mayor’s Office]

The waterfront property along Wallabout Bay in Brooklyn, New York, has been home to industry for centuries. After the Revolutionary War it was used to construct merchant vessels, and in 1801 President John Adams authorized the purchase of some 40 acres there and established the site as a naval shipyard.

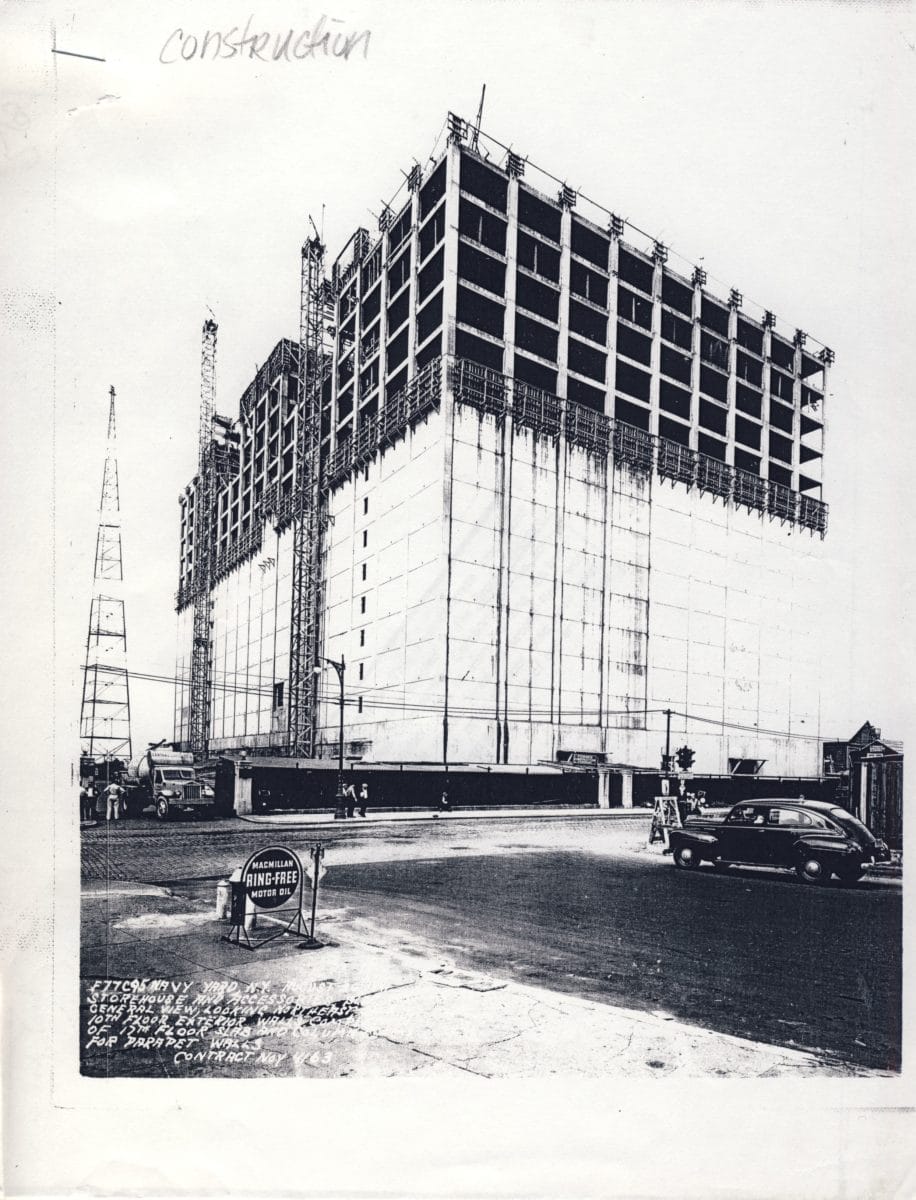

In the run-up to World War II, the Brooklyn Navy Yard doubled in size, expanded its workforce to 70,000 employees (including, for the first time, women), and became known as the “can-do” yard for its outsized, enthusiastic contribution to the war effort. That’s when the Navy constructed Building 77, a massive, 1 million-square-foot structure; the bottom 11 floors stored dry goods, and the top five housed offices for naval officers overseeing the North Atlantic fleet.

Building 77 was first built to store dry goods as well as house offices for naval officers overseeing the North Atlantic fleet. [Photo: Courtesy of NYC Mayor’s Office]

Fast forward to 1966, when the Navy Yard was decommissioned and began its life as an industrial park. Private companies continued to build ships there for another decade or so, but as American manufacturing declined, so did the yard, and until the ’90s it laid mainly dormant. Now, as Brooklyn is becoming hipper, techier, and more vibrant than ever before, the yard is changing, too. The Brooklyn Navy Yard Development Corporation, a nonprofit corporation that serves as the yard’s developer and property manager on behalf of the City of New York, envisions the yard as a major player at the intersection of manufacturing and technology in the 21st century.

At the heart of that vision is Building 77, which represents around a quarter of the total building stock on the yard. The development corporation partnered with Marvel Architects and Beyer Blinder Belle on an ambitious renovation of the structure, reimagining it as a modern space for tech-centric manufacturing and light industry, with a 60,000-square-foot food court on the ground floor.

Russ & Daughters, the famed New York City purveyor of smoked fish, has signed on as the anchor tenant and will have a retail storefront at Building 77 as well as commercial cooking space. When it opens in 2018, the cafeteria will be open to the general public, drawing people to a section of Brooklyn that was—until now—short on amenities.

In 2018, Building 77 will also be home to Russ & Daughters, famous NYC purveyor of smoked fish. [Rendering: Courtesy of NYC Mayor’s Office]

For years, the yard was only open to the people who worked there, frustratingly cordoned off behind walls and fences that hid much of it and the waterfront from view. The Building 77 development represents a major opportunity for residents to engage with a major fixture in their neighborhood. “What’s the one thing you want to do when you walk along that wall?” says Scott Demel, director of operations at Marvel Architects. “You want to see the other side.”

To encourage pedestrians to step up to the building—which they’ve known for decades as an imposing concrete building looming over the street—the design team placed its main entrance along Vanderbilt Avenue, one of Brooklyn’s larger thoroughfares. “There’s this urban connection,” Demel says. “We want to be part of the neighborhood.” Inside, the food hall runs along one of two railroad tracks that is embedded in the floor. Where it used to carry in naval supplies, it will soon guide in Brooklynites looking for a snack.

[Photo: Courtesy of NYC Mayor’s Office]

The low-lying Navy Yard was ravaged by Hurricane Sandy in 2012, so storm resiliency was top-of-mind for the design team. The entire first floor of Building 77 was raised 18 inches, putting it well above the level mandated by building codes. That also created a space for food production tenants to run piping under the current floor but above the reinforced concrete of the original one—the original base was so strong it would have been practically impossible for tenants to cut through, making it more difficult for them to install the infrastructure they need. And to foster a sense of connection with the Navy Yard as a whole, the far end of the food court features large windows that give occupants a front-row seat to the happenings inside the yard.

A word about those windows. Converting a naval warehouse into an attractive space for businesses was no small task, and with Building 77, the team was trying to build the core and shell to LEED standards to boot. That was especially complicated because the first 11 floors were originally constructed to house dry goods, not people, so they were made from solid concrete and completely devoid of windows. To adapt the space, crews punched through the walls to create nearly 400 new windows, removing some 3 million pounds of concrete.

Overall, it was a massive undertaking—hence the more than $140 million price tag (it was primarily funded by the city). The reward, Demel says, will be the more than 3,000 jobs that will be created with the building and, if things go as expected, the revitalization of an entire neighborhood.

[Photo: Courtesy of NYC Mayor’s Office]