Flexibility is Key to Designing Resilient Cities

Approximately 2.5 billion people are expected to be living in cities by 2050, according to the UN Department of Economics and Social Affairs (DESA), and COVID-19 has become an undeniable catalyst for change across all facets of city life.

Communities are under constant transformation—every city’s needs, as well as those of its citizens, are continually evolving. Our cities must adapt to change—climate change, behavioral change, and change in community needs—and make room for flexibility in urban planning, urban design, programming, and management of urban space.

Cities are grappling with uncertainty. To withstand future natural and man-made disasters and become more resilient, investments need to be made around maintaining and upgrading critical infrastructure—including in affordable housing, transit, water, energy, health care, and internet access, and in the protection of natural assets and reduction of our carbon footprint.

Livable mixed-use communities where people shop, relax, and work out, all within a walkable distance from their homes and places of work, have been shown to be better equipped to handle a health crisis, economic lockdown, and financial downturn. These so-called 15-minute neighborhoods are at the center of a resilient urban system—the culmination of 10 key principles, of which flexibility is key.

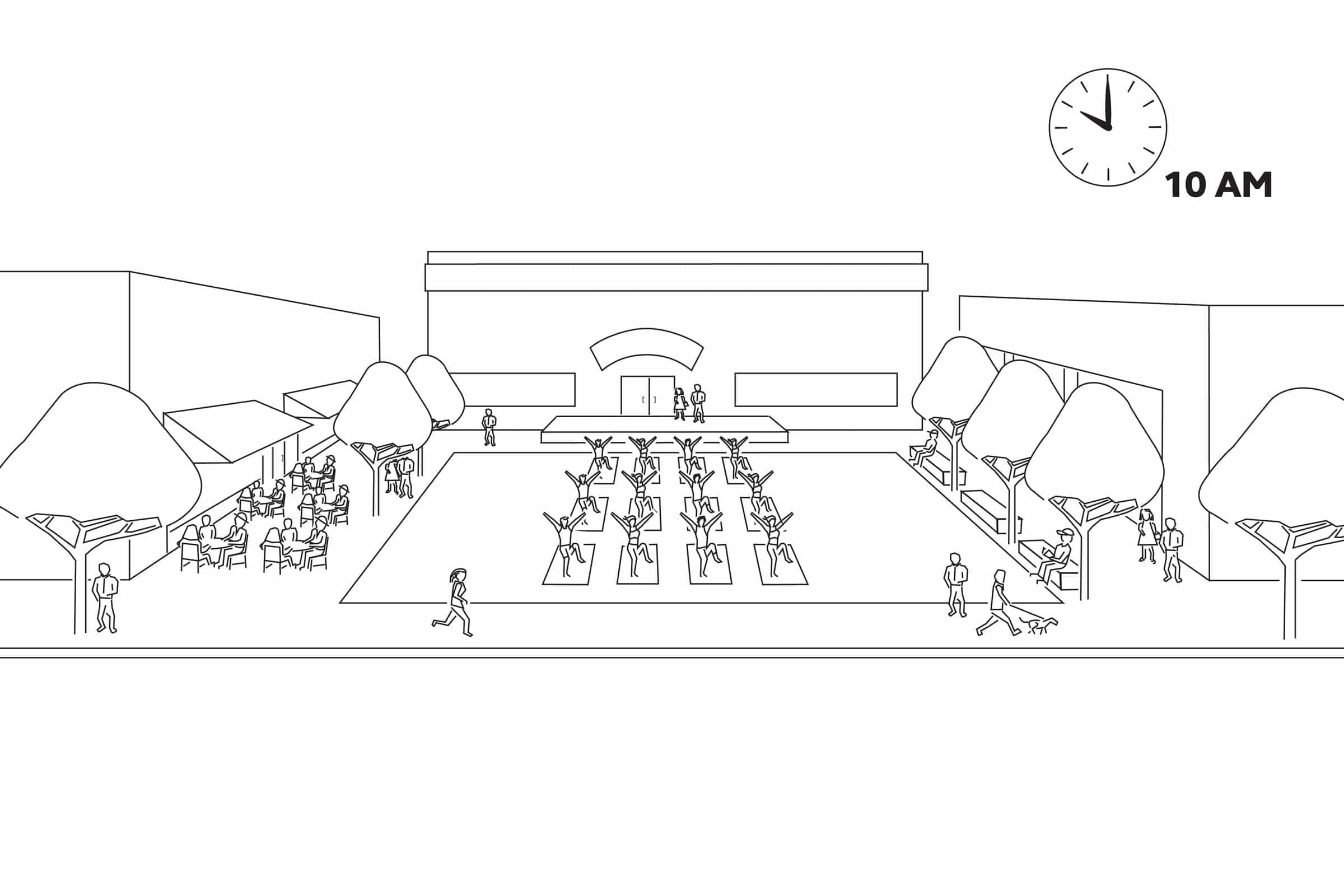

Consider Flexible Uses

Image courtesy of CallisonRKTL

COVID-19 has shown the world that spaces that once served one function must now accommodate a variety of needs. Buildings are built to last a lifetime, and some are more suitable for adaptive reuse and can more easily be retrofitted than others. Industrial warehouses and loft buildings built for manufacturing with high ceilings and open floor plans in a dense urban setting have been successfully converted into office space, residences, and hotels. The challenge will be to reinvent suburban corporate headquarters, office parks, and shopping malls, and to find new uses for buildings designed to serve a specific purpose but that have outlived their useful lives, like transit facilities or research labs.

Allow for Shorter Leases

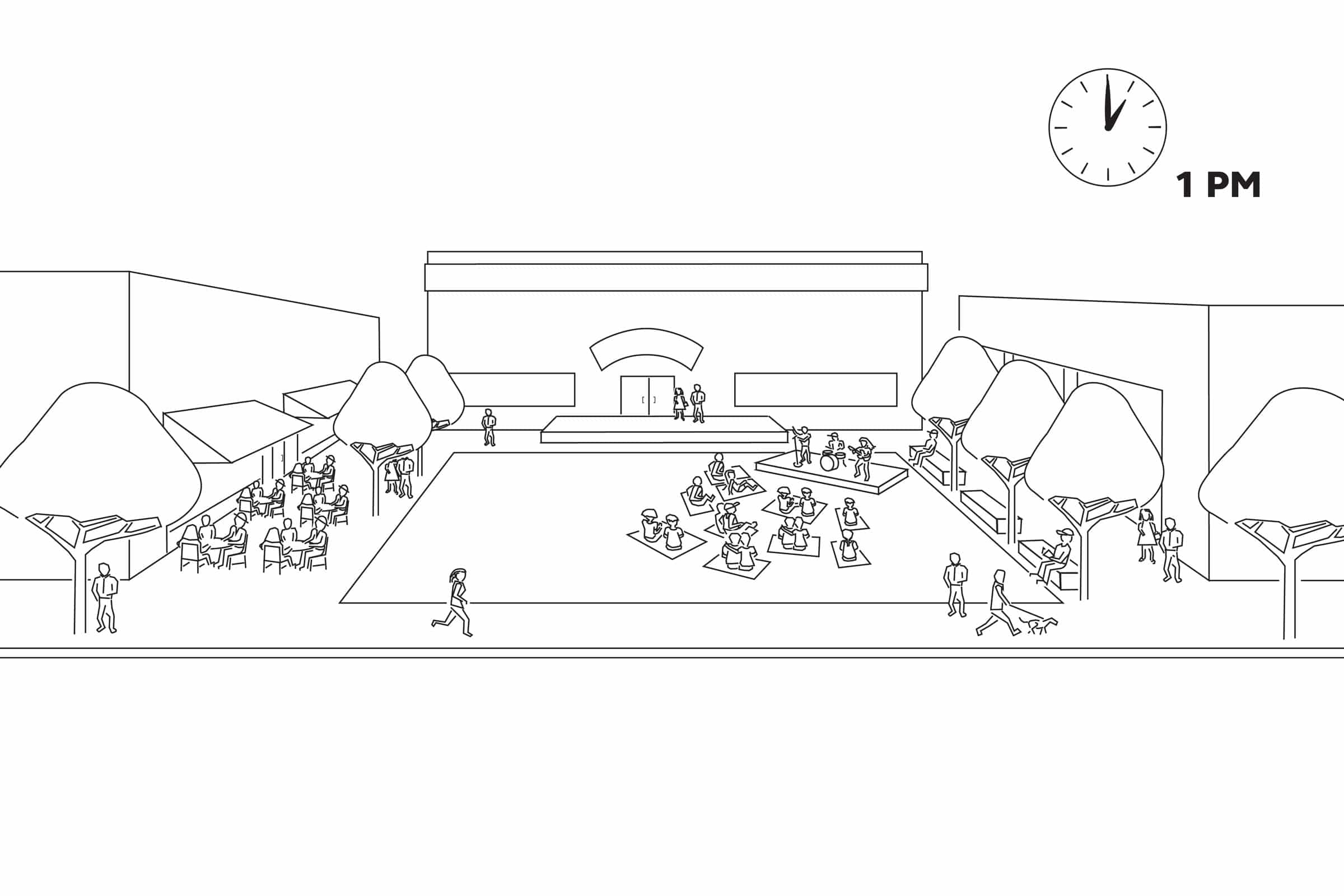

Image courtesy of CallisonRKTL

To ensure buildings can be used to their fullest potential, they should offer living and working solutions that can be catered to the occupier’s evolving needs or altered to accommodate new uses. For office and retail space, allowing shorter lease terms could be a way to create flexibility without drastically changing the building.

Using semi-automated systems, rooms can also be adapted far quicker to a user’s needs and to suit new lease terms. Longer term solutions need to consider adaptive reuse of existing buildings and new mixed-use building typologies.

Plan for Mental Health

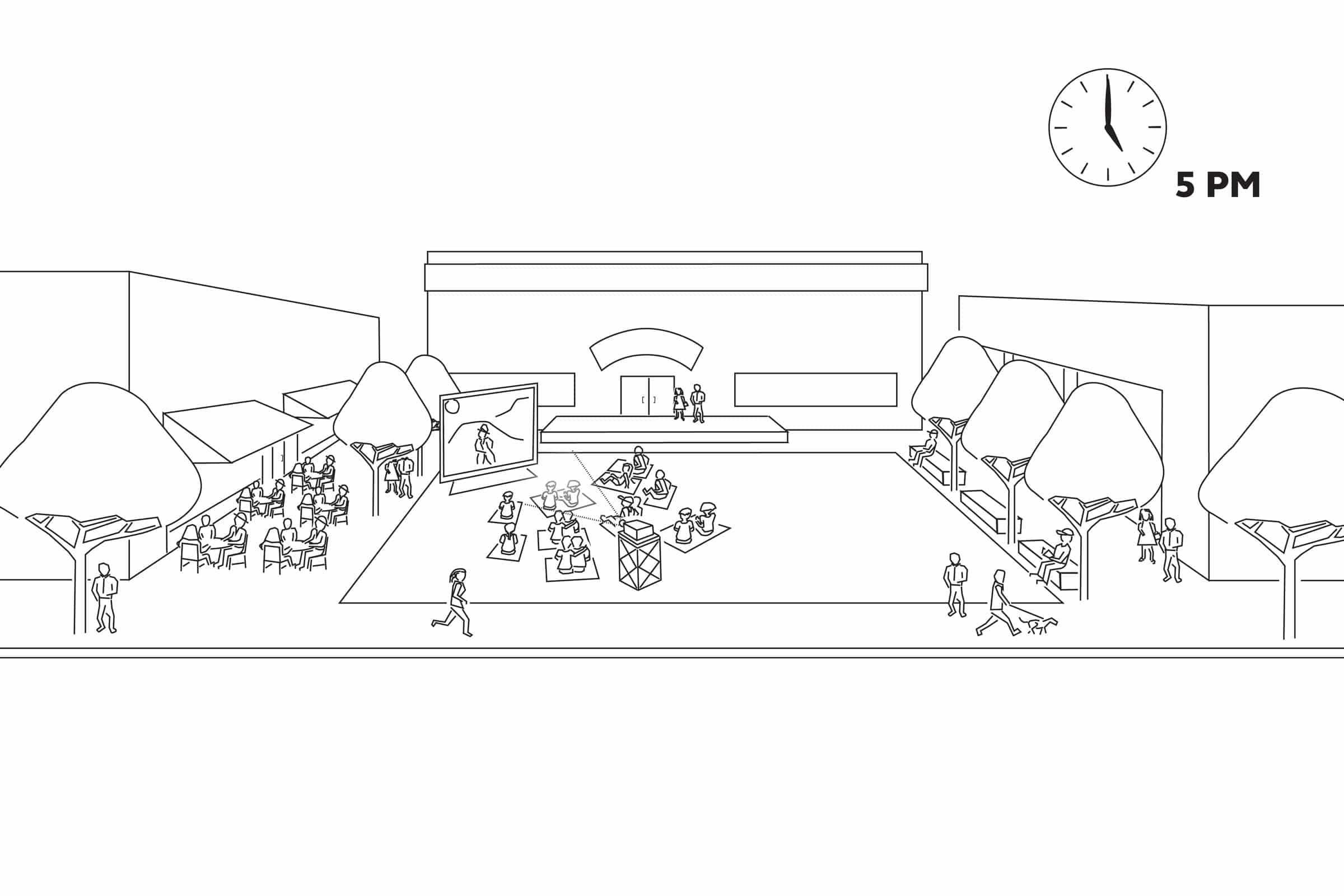

Image courtesy of CallisonRKTL

In a recent study conducted by global experts on cities and mobility, 88% said COVID-19 will prompt a shift to working and living in areas with more green and open spaces as well as urban amenities within walking distance. As most people have spent most of their time indoors over the past few months, there is a greater understanding of how physical spaces impact physical and mental health.

While last year lacking a green roof, backyard, terrace, or nearby park might not have been a big deal, it’s now one of the main concerns for city dwellers. Simple greening and gardening solutions aside, the reality is that many people who live in cities are without their own private outdoor space; cities must better plan urban neighborhoods to offset this with their proximity to open green spaces.

One way to intensify the use of limited open space is to program the space for a range of activities at different times of the day and week, plus seasonal programming.

To create more open space many cities have introduced open streets programs, closing streets for vehicular traffic and allowing businesses to take over outdoor space to serve customers. Longer term we need to continue to prioritize people over cars, turning parking lots and overly wide roadways into publicly accessible and usable open space.

By creating 15-minute neighborhoods, we reduce traffic and travel times and improve the environment by minimizing the need for a car. People would also be organically encouraged to support small businesses and eat locally sourced produce.

In addition to a mix of uses, we need a balance of density and diversity that fosters the exchange of ideas, collaboration, and innovation and ensures future prosperity, health, and well-being.

What’s Next?

The pandemic shocked our cities and highlighted their vulnerabilities. No city was immune and, while the crisis response and innovative solutions of many are to be applauded, the change we need goes beyond tactical urbanism. We need to rethink land use regulations, building codes, and urban policies that lead to the persistence of bias and inequality and how we control, manage, and regulate public space and amenities. We need to determine where and how the desired mix of uses can be achieved while reducing the access radius for living, working, shopping, and entertainment and creating a more integrated urban fabric.

The kind of programmatic change and the level of flexibility we are seeking to introduce requires a willingness to turn the disruption caused by COVID-19 into an opportunity for lasting change. If nothing else, the events of the last year provided an impetus for such a thing, with public and private, council and citizen now aligned in doing what is needed to make possible this future where 2.5 billion people not only live in our cities, but do so healthily and happily.