Story at a glance:

- The materials for exterior facades are changing, as architects move away from glass.

- Modern facades increasingly need to meet aesthetic and performance needs.

- SOM’s 28&7 project uses custom black glazed terra-cotta from Shildan Group.

A classic tuxedo, a little black dress, an elegant building facade. One of these things is not like the others, but it’s the feeling of a luxurious, understated garment that Michael Kirchmann and his colleagues were after with 28&7. The new Class-A boutique office building in the Chelsea neighborhood of Manhattan had to be eye-catching while fitting in with its environment. It also had to be high-performing. The solution, in part, was black glazed terra-cotta from Shildan Group.

Designed by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM) and completed in 2022, the 28&7 project was influenced by its surroundings—especially that of the neighboring Fashion Institute of Technology. “28th Street has a number of powerful buildings with a rhythm of large-scale window openings. We wanted windows that were as large as possible for the tenant experience without making an overwhelmingly glass building,” says Kirchmann, CEO and cofounder of GDSNY and a former SOM architect.

Kirchmann says the problem with all-glass towers, while offering impressive views, is they often feel like they could be anywhere. “Our interest at GDSNY is different; we’ve always wanted to infuse a more tactile look and feel to our projects to give them a sense of difference, of place, and of context,” he says.

The 28&7 facade draws inspiration from the neighborhood—an area rich in 19th- and 20th-century masonry buildings, with a cladding selected for both its customizable and sustainable properties.

SOM Design Partner Chris Cooper says the team paid special attention to the historic typologies around them when they set out to interpret 28&7. “How do we almost defiantly do a modern building in a historic context?” he says.

The design team began by considering the characteristics of a historic building compared to modern masonry. “That acknowledges depth of the facade. It acknowledges a grid like the warehouse-esque buildings around us, and it recognizes a certain amount of opacity,” Cooper says.

He says SOM always looks carefully at the performance of walls, too. “We’re looking more carefully at the carbon footprint of those walls, and that has an aesthetic impact.”

Choosing Terra-Cotta

- Large floor-to-ceiling windows at 28&7 flood the interiors with natural light, with corners that are fully glazed. For exceptional energy efficiency, the windows are triple-glazed and incorporate a low-e coating. Photo by Dave Burk, courtesy of SOM

- SOM and GDSNY celebrated the opening of 28&7 in 2022 near Pennsylvania Station and Herald Square. The 12-story building with facade from Shildan Group is on target for LEED Gold. Photo by Dave Burk, courtesy of SOM

For 28&7, Cooper says the support didn’t need to be as large as that of historic buildings. They were able to thin down that masonry figure and reshape it in a way that felt uniquely modern. “We’re not building a load-bearing wall today; we’re building a wall that is more of a rainscreen or a cladding on the opacity,” Cooper says. As such, they thought terra-cotta could be the perfect material.

“We were very enamored with terra-cotta as a material. It is having a real renaissance in its modern form of extruded terra-cotta versus the historic pressed terra-cotta we know from all around the city. We like that it’s a natural material, but it’s also a very versatile material,” Cooper says.

SOM had worked with terra-cotta before, collaborating with Shildan Group on another NYC project that incorporated white glazing. When it came time for 28&7, the team knew they wanted something special. They returned to Shildan to push the envelope even more. “We were looking for extra depth and extra reaction to the light—and to do that in a way that was contrasting with the context, which is a very neutral buff tone masonry,” Cooper says.

The Perfect Black

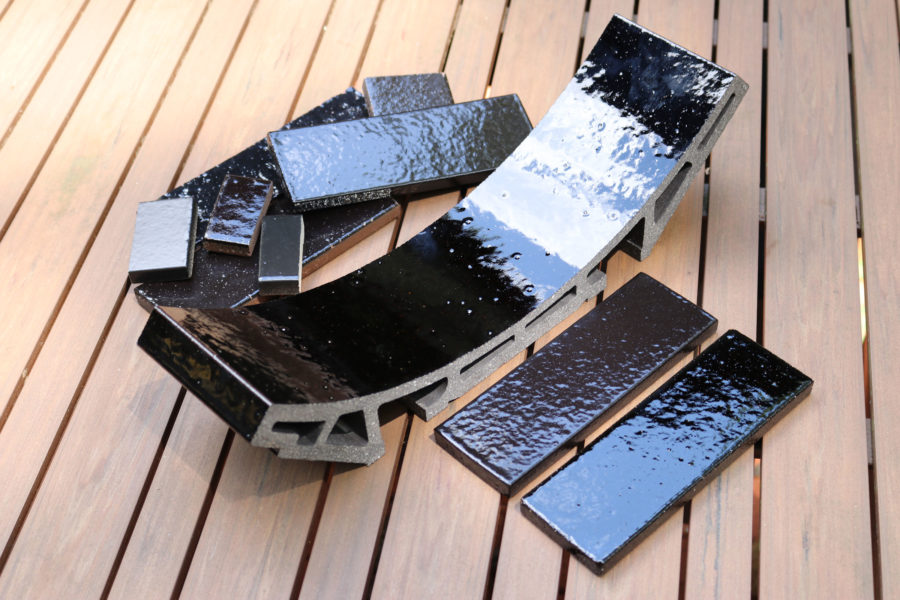

Shildan Group worked closely with SOM to perfect the exterior at 28&7, using a black glazed terra-cotta they spent months developing. Photo by Andreas Suess

“We knew from the get-go that we wanted a black building, which was also a statement about being next to one of the world’s foremost fashion schools,” Kirchmann says. “The black also punctuates the building’s prominent corner in a way that gives it so much presence.”

Before this project, Shildan Group President Moshe Steinmetz would have said there is only “one black.” Today he laughs, saying he now knows from experience that there are more. “We went through four or five other blacks for glazing,” he says. “It wasn’t as easy as I expected.”

To finalize the color, the SOM team toured the Shildan Group factory in Germany to explore different blacks, different curved shapes, and how the light reflected on each. They worked hard with Shildan to get the right composition of glaze and clay body color to get the terra-cotta as dark as possible.

“We were intent on using exterior materials that had texture, color, and profile—almost like a textile,” Kirchmann says. He says terra-cotta has a long history that has “undergone quantum leaps in its manufacturing process” to a point of nearly endless variations in form and color. “We spent months and months during the design process making sure we would get the effect we wanted from the terra-cotta. It was quite fascinating.”

Steinmetz says the final result responds to the light beautifully, making the facade dynamic and playing nicely off the glass.

Evolving Exteriors

Black glazed terra-cotta developed for 28&7. Photo courtesy of Shildan Group

Cooper says many architects are moving away from all-glass buildings because they don’t provide the best performing walls or always stand up to code, which requires 40% opacity. “I think we’ve all learned that the window to wall ratio is very critical in the performance of these buildings, so we’re looking for other materials for opacity, and we’re also looking for articulation of buildings,” he says.

Steinmetz also thinks people will continue to move away from glass. Imagine, he says, if 28&7 on the corner was all glass. “It would take away all the character of the building. Now when you look at the building you can see it’s like a jewelry box,” he says. “It’s an amazing, gorgeous building.” If it were simply all glass, he ventures to guess he wouldn’t even notice it. “What we have with terra-cotta is the ‘wow’ effect.”

Steinmetz expects to see exterior facades continue to evolve to allow for even more unique shapes, including integrating those into more curtain wall systems. He expects to see facades of the future actively participating in creating energy for buildings.

When Shildan Group began more than 25 years ago, terra-cotta was mainly used in flat panels—most of which were red. As technology and production improved, the company began to see what else it could do. “We started introducing glazing. Ten years ago only 3% of the jobs were glazed. Now I’d say 80% are glazed,” Steinmetz says.

They also began seeing a demand for three-dimensional shapes and an expansion of where terra-cotta could be used—including on curtain walls. “No more of those boring, rectangular aluminum extrusions but really introducing cladding to those volumes to make a building much more interesting.”

Sustainability

Besides being made of a natural material—clay—terra-cotta is fire-resistant and non-combustible. Shildan Group also uses no lead in its glazes.

Cooper loves terra-cotta in large part because it’s from the earth. “That gives it a relatively low embodied carbon footprint, and it also has the tactile beauty of a natural material. It’s incredibly versatile as a material in terms of profiling, color, finish, the types of glazing—you really can take an artful approach to material,” he says. “You are not just selecting a material and putting it on a building; you are selecting a material that you can then sculpt. As a designer it’s a very appealing material to work with because it gives you a lot of flexibility of effect by manipulating the various profile options and finish options.”

Shildan Group also considers efficiency along every step of its terra-cotta manufacturing process, as the company continues to explore ways to use less energy to create its product. “If you take the amount of energy and compare it to the lifespan of the product, it’s pretty low,” Steinmetz says.

They also recycle energy from the kiln to the dryer and have a recycling plan to grind unused terra-cotta to be used in the next production. The clay is harvested locally.

Cooper hopes building facades will eventually exceed carbon neutral. “We have to recognize the role of buildings in carbon emissions globally,” he says, hoping for future buildings that are carbon negative. SOM is currently in the midst of research around carbon-absorbing building materials.

Experimentation

Cooper says everything you get from Shildan Group is a custom solution, and architects get to be as hands-on as they like in developing the perfect exterior for their project. “From the get-go the assumption is you are working with them to build a custom product for your project. That’s very appealing,” he says.

He says Shildan Group also has the special equipment and processes in place to make architects’ dreams come true. “They make it very easy and enjoyable to find the right profile, finish, and material for the project. We’ve even worked with them on inventing a unique brick profile—an extruded brick.”

Cooper says architects have a responsibility when they design in these exciting neighborhoods. “To find a way to not make the neighborhood generic, to enhance the character of the neighborhood in a way that’s inherently up-to-date. That’s really fun.”