Story at a glance:

- In a circular economy objects and materials are reclaimed, remanufactured, and reused.

- Current circular design discussions center around regenerated nylon and more.

Here’s a startling statistic: By 2050 we will consume three planets worth of resources.

If you haven’t felt the gut punch of the last sentence yet, here’s another: Construction is responsible for more than 30% of resource use worldwide, plus 23% of global greenhouse gas emissions, mostly from material production.

Whether it’s a building, interior, or object, materials are the cornerstone of any design. But the reality is, resources are dwindling. And as they do architects and designers must get smart about the ways they tie function and aesthetics together to bring a space or designed object to life. We may not be able to get back resources that have been depleted, but we can collectively prevent sources from diminishing further. It starts with embracing the circular economy.

In a circular economy objects and materials are reclaimed, remanufactured, and reused. Unlike recycling, which focuses on finding the right way to dispose of waste at the end of its life, a circular approach looks to prevent waste from the start.

“The way I like to think about it is, what you’re putting into the world today, you’re going to see again tomorrow,” says Marcus Hopper, senior design manager at Gensler, based in San Francisco. “As a designer you need to think about when you put something in, how it’s going to be used again, either by you or somebody else.”

Circularity isn’t new, but most of the industry is just beginning to shift to a circular approach. Really it’s not so much a shift that is needed but a complete transformation, as designing for circularity will require changes in thinking, process, and practice—not to mention collaboration from all fronts.

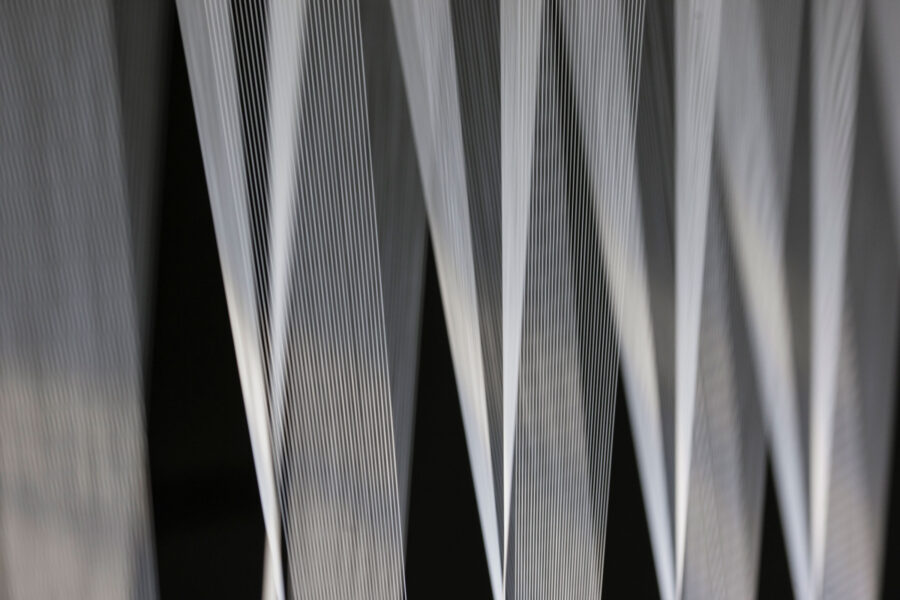

Meanwhile others are ahead of the game. In 2011 Aquafil, the leading manufacturer of synthetic fibers for the textiles industry, for instance, introduced a regenerated nylon material called ECONYL®—a fiber made from nylon waste otherwise polluting the planet that can be recycled and recreated into something new infinitely without additional resources.

“Nylon is a versatile material that plays an integral role in almost every product—from flooring to furniture to textiles in automotive and fashion,” says Giulio Bonazzi, chairman and CEO of Aquafil. “However, we needed to find a way to reduce its environmental impact. Nylon is typically made using oil derivatives that are high energy-consuming and high emission-producing. But how do you change a material we’ve been using for more than 100 years?”

Today a circular future is more tangible, but the experts at Aquafil say we still need buy-in from all parties to make the shift.

The Shift Toward a Circular Economy

- The Beaumont Range Collection from Interface was created with ECONYL nylon. Photo courtesy of ECONYL by Aquafil

- Luna Yellow Gold was designed by Rols and created with ECONYL nylon. Photo courtesy of ECONYL by Aquafil

Let’s take a step back.

The circular economy was first coined in 1988, in Allan Kneese’s The Economics of Natural Resources. Yet here we are, nearly 40 years later, still struggling with how to push it forward.

“It’s never really been built into the design system,” Hopper says. “Historically, if you’re thinking about implementing reuse, the process is still very linear. It’s based on schedule, time, and costs. And to start to turn it over, it takes the entire industry to do that. It’s going to take not only the architects, clients, and consultants, but also it’s going to take government agencies with policy to help us turn that linear process that we’re all so used to into a circular process.”

Bonazzi agrees. “In order to change the world, we need the collaboration of the entire value chain,” he says. “Without good collaboration, we will never be able to change the world on a large scale.”

Places like Europe already have that government support. The circular economy action plan (CEAP) went into effect there in March 2020 to reduce pressure on natural resources, stop biodiversity loss, and support the European Union’s 2050 climate neutrality goals. Last year the EU also published a directive on making textiles circular before 2023. No such circular policies exist in the US.

Lack of policy is another barrier to circular success, sure, but the industry—and planet—can’t wait. To be successful designers must implement circular economy strategies early into the process. And even in the beginning they must think of disassembly and end of life.

“Designers have to think in reverse,” Hopper says. “Don’t think, ‘I’m going to design it, then I’m going to find the material and specify it.’ Design is what you have. You have to look at what’s available versus starting with something new.”

In a way the design thinking required for today goes back to the elemental building inspiration we had as children. “Architects and designers, they were the folks building things out of cardboard boxes when they were kids,” Hopper says. “You have to go back to that mindset, where you get that box, take it apart, and there are all kinds of materials. That’s what you have to a build a fort. It’s really thinking about materials as a possibility. Creativity is needed, and that’s where architects and designers shine.”

The Circular Economy in Practice

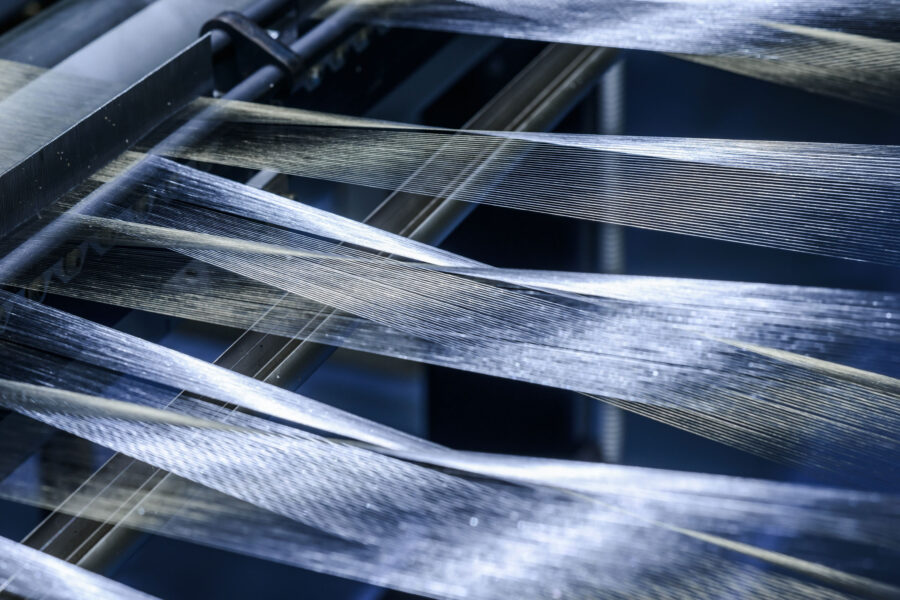

ECONYL nylon is made in the Aquafil Arco facility. Photo courtesy of ECONYL by Aquafil

Back in 2006 when Aquafil began to develop ECONYL nylon, the challenges were so numerous Bonazzi jokes that if he knew then what it would take to create it, he might have never done it.

“The process starts with trying to understand where products end their life,” he says. And by end of life, Bonazzi clarifies that, in the circular economy, we are talking about the end of a product’s first or second use. Not every waste product can be recycled, though, which is where the first complication arises.

“Waste is not a standardized product. You have to be prepared in the beginning that every scrap you are taking home is different than the previous one,” he says.

In developing ECONYL nylon, Aquafil had to transform itself into a sort of waste management company. Through lots of trial and error, it identified two viable waste streams: recycled carpets and discarded fishing nets. The next challenge was developing, as Hopper said, a reverse logistics system to not only obtain waste but also transform it into a regenerated material. In essence, Aquafil had to invent an entire supply chain.

Creating a new way of working is not an option for every designer or manufacturer, but there are other ways around it. The City of San Francisco Department of the Environment, for instance, received grant funding to create an online materials marketplace where designers, manufacturers, contractors—everyone—have access to information on materials available. Though regional in location, other states have received similar funding, and these marketplaces have begun to pop up around the country. “It creates more of an inclusive environment so everyone can participate in the circular economy,” Hopper says.

Last year Hopper also participated in a research project with the San Francisco Department of the Environment to study materials more deeply. “We wanted to look at and analyze materials that could potentially be coming out of projects 10 years out. What are those materials, and when they come out of projects, where are they going to go?” he says.

Storage of materials, especially in a city like San Francisco, is expensive. The concept they landed on was the Building Resources Innovation Center (BRIC), a physical space that would temporarily store and redistribute salvaged and surplus building materials. “The idea goes back to time. If materials are not ready to go to a new site yet, they would sit at a site like BRIC, and then go to the site that they were meant to go to,” Hopper says.

The city worked with California’s Department of Transportation to rent staging areas under the interstate—essentially large open parking lots—to host these material retail pop-ups where contractors, designers, and architects could come and shop. BRIC also worked with the online exchange to tag materials as they came in and included community partnerships to educate and engage the local community.

The city is currently applying for funding from the EPA to keep BRIC going, and Hopper is hopeful. “BRIC is a great example of how the circular economy can work that could be applied anywhere.”

The Road to Circular Success

ECONYL regenerated nylon is being spun into spools. Photo by Peter Skrlep

Like anything, the path to a circular economy is a learning process. ECONYL regenerated nylon didn’t just appear one day; Bonazzi and the Aquafil team made the infinitely recyclable material happen because of years of research, waste collection, innovations, and system changes. It was a long process—but a necessary one.

“You have to talk about and implement circularity for many different reasons. First of all, it’s the right thing to do. In the medium- to long-term, the availability of raw materials will be less and less. The crisis of raw materials will grow indefinitely,” Bonazzi says. “We are trying to create a new world for plastics and fibers that can be regenerated to open the doors to solutions. Making raw materials from renewable sources, recycling them at the highest possible level without the necessity of taking new resources from the planet—this is our vision. This is where we want to go.”

As for the rest of the industry, there is still a lot of work to do to create a circular economy. But with full industry and government collaboration, a new way approach to design, and experts like Bonazzi and Hopper leading the way, it is possible. The industry can get there. It has to.

“We have a long, long journey in front of us, but I’m also seeing that the industry is reorientating. Of course, the speed of change will be dramatically influenced by the legislation. If legislation pushes toward the right direction, everybody will move much quicker,” Bonazzi says. “But do we have an alternative? No, I don’t think we do.”

The Alcarol Wave Screen was created from melting fishing nets and ECONYL. Inspired by ocean waves, the Wave Screen is an abstract reflection of the fragile condition of our oceans. Photo courtesy of ECONYL by Aquafil

ECONYL nylon is used by more than 2,500 design and fashion brands. Photo courtesy of ECONYL by Aquafil