Story at a glance:

- Brooklyn-based architect Anton Bashkaev puts forward a community-driven concept that could change the way we live, work, and play.

- Many of today’s architects look to move away from cold, private architecture and design for togetherness.

- Crown House aims to foster an environment of mutual acknowledgment, education, and collaboration in a formerly vacant site.

This is the story of 21st-century architecture and how it can generate a sense of home in us again. For the last century many architects were enamored with utopian concepts that brought us the modernism style, Bauhaus, and machine-inspired aesthetics that alienated people from their living environment. Sharp corners of glass and steel facades, the sterile seriousness and cold detachment, made architecture impenetrable and hard to enjoy.

Our generation is waking up. Overwhelming time spent in digital space has to be balanced with a humane physical environment—not to be reinforced by machine-inspired aesthetics of sleek, pixelated, or AI generated shapes of buildings.

I was raised in a Soviet modernist residential neighborhood. Following the behest of Le Corbusier, multi-story concrete panel towers look at each other over vast grass-seeded areas framed with asphalt sidewalks along highways. There was an absence of street facades and any sense of private or communal ownership, which atomized local residents and created a city of dwellers, but not citizens. The notion of community was virtually nonexistent—the first time I heard this word was in my master’s program in England.

A New World

My most eye-opening experience was when I moved to Crown Heights. Getting to know the faces behind the facades and being connected to the multigenerational, multicultural life of the neighborhood was energizing.

Throughout the pandemic, thanks to the local park, people remained in social relation to each other, turning a once dangerous park into a buzzing, joyful island, living by the rules of social distancing.

By the time the war broke out in Ukraine I’d been living in Crown Heights for four years. Its Crimean precursor was the reason I left Russia in 2015. When political protesting became illegal my family was forced to leave the country under the threat of incarceration.

This was an existential moment. While working in the US I haven’t yet become a full resident, but Crown Heights showed me the value of true community and gave me a sense of home. I was received not as a citizen of an aggressive state but as a neighbor and friend.

Crown House Project

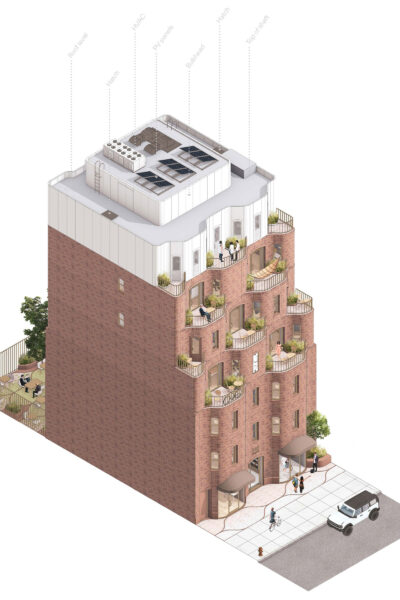

- Rendering courtesy of Anton Bashkaev

- Rendering courtesy of Anton Bashkaev

As a professional architect, I discovered a vacant spot belonging to an educational organization and tasked myself to come up with the best realistic concept. It’s now called Crown House. I wanted to strengthen the existing community and address its issues, doing the job Brower Park does so beautifully as a public space. My goal was to design a social hub with an equally high ethical and aesthetic value.

To involve all the communities of Crown Heights and create synergy between programs I allocated one program for each community to ensure they correspond with and amplify each other. These groups are the Hasidic Jews of Chabad Lubavitch, African Caribbean Americans, and young professionals from all over the world. Their respective programs are an education center, café, and bookstore, each of which will occupy one-third of the first level and have its own entrance. Inside will be lateral passages connecting them, including access to the backyard that can be used by all three.

The Jewish educational center will have a lobby on the first level that leads to the elevator and stairs to the floors above. Here they can hold classes and meetings as well as accommodate overseas students and visiting professors. A Jamaican-style café will serve Blue Mountain coffee and traditional Jamaican desserts. In between there will be a bookstore for young professionals who have moved into the neighborhood, as well as a great selection of books for all youth.

Rendering courtesy of Anton Bashkaev

All of the programs will correspond with each other. The café will recommend books at the bookstore, which in turn will promote events at the educational center. The students of the latter can also enjoy discounts at the café. The after-hours use of the educational center space is important to engage with the larger community and different age groups, with Spanish classes, guitar lessons, and a diabetes prevention group.

The top floor of Crown House will have a lounge for the education center that hosts external events, celebrations, and symposiums. Levels four, five, and six will have dorms for overseas students and studio apartments for visiting professors.

On the lower levels the language of the site’s historical architecture allows for more than residential use. The bay window facade of the demolished buildings has been used as a module for the new design, preserving the previous massing and matching the height of neighboring cornices, gently recessing upward to provide space for the residential terraces on the top levels. This program is crowned with a fully glazed lounge on the top floor, which serves as the main rentable asset of Crown House.

The introduction of these terraces not only enhances the living experience of the residents, but it also contributes to the safety of the street by increasing the onlookers’ presence in the public space. The friendly brick-clad curves and local species of wildflowers planted in the corners of the terraces add warmth and friendliness to the image of Crown House, encouraging communities to use the public space even more, continuing the legacy of Brower Park.

Crown House is an example of modern architecture that has been thoughtfully integrated into the historical fabric of the city. Rather than changing it, it heals and amplifies, bringing the community to the forefront of architectural attention on both ethical and aesthetic levels.