Story at a glance:

- ZGF’s District Carbon proposal won Seattle 2030 District’s 2021 Energy Roadmap competition.

- Building integrated teams and enhancing infrastructure among the ways you can transition to zero carbon.

- Opportunity exists for district investment across the country. This can take different shapes in response to different climates, energy grids, zoning, building stock, and Covid-related market forces like vacancy rates.

In the pursuit of rapid decarbonization, investing in the adaptive reuse of cities at the district scale can address issues of equity, mobility, embodied carbon, and the electric grid. In a carbon footprint study of 13,000 cities, the authors conclude that because carbon emissions are highly concentrated in affluent cities, “targeted measures in a few places and by selected coalitions can have a large effect covering important consumption hotspots.” In other words, the potential impact and carbon savings of district-scale sustainability initiatives far outweighs the slow, incremental changes currently being implemented by US cities and states, which are not moving the needle fast enough.

Car transportation, in particular, accounts for a significant portion of city carbon emissions, simply from people commuting to and from work, driving around town for errands, and accessing amenities in urban cores. The highest potential to reduce the carbon footprint of households is to be near urban cores, according to a study and calculator of US household carbon footprints. The study found that “the variable with the strongest correlation with total CO2 per household is the number of vehicles per household.” A study by the Atlanta Regional Commission confirms “living near major activity and employment centers as well as near historic town centers reduce CO2 emissions from transportation.”

This is obvious to Mayor Anne Hidalgo of Paris, who has championed the 15-minute city concept that focuses on “proximity, diversity, density, and ubiquity” to bring work, home, and play within range of pedestrians and bikers.

Adapting our existing buildings and infrastructure into mixed-use districts has the added benefit of reducing Scope 3 emissions from new construction and regional supply chains. According to a Carbon Leadership Forum study, the median embodied carbon in a new multifamily building (including the structure, foundation, enclosure, and interior) is approximately 42 kg/CO2e per square foot. This equates to 42 metric tons for a single household occupying a 1,000-square-foot apartment. These emissions can eclipse operational carbon (from heating, cooling, lighting, cooking, et cetera) in locations with a mixture of renewables in the electric grid.

Cradle to gate embodied carbon—or all the emissions from extraction, manufacturing, and transportation of building products—in new construction can easily exceed 25 years of operational emissions, assuming today’s grid emission factors. This will dramatically change as utilities approach zero emissions between 2030 and 2050. However, these estimates are on the low side, as we do not yet have good data on the embodied carbon from siteworks and MEP systems, nor does this include emissions from rehabs and replacement of items like windows. Bottom line, embodied carbon in buildings is the highest priority for designers after transportation. And transforming existing buildings avoids much of the embodied carbon associated with its sourcing and construction. Unlike transportation and operational carbon, which are emitted over time, all of the embodied carbon goes into the atmosphere upfront on day one—so there is real incentive to minimize embodied carbon in supply chains and look at reuse, and biogenic, carbon-sequestering materials.

At the same time, cities and states are moving toward stricter energy codes and clean building legislation to advance their sustainability goals, like Washington’s Clean Building Act and New York’s Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act. Building owners and developers have an opportunity to get ahead of public policy by considering more holistically how to reposition their properties not only for energy and carbon emission compliance, but for structural life safety and resilience, total electrification, occupant health and well-being, and mixed-use programming that activates the city and helps address affordable housing shortage across the country.

All of this costs money, and many owners have little incentive to invest more in properties beyond basic maintenance. The Clean Building Act, which requires energy audits and target energy use intensity (EUI) for existing buildings, is only projected to lower state emissions by 4%. For those hoping electric vehicles are a silver bullet to decarbonization of suburban lifestyles, there is high uncertainty around the supply chain emissions and social justice impacts of extracting cobalt, lithium, nickel, and copper needed in massive quantities for EV batteries. Even if a Tesla’s tailpipe emission is zero provided by a 100% renewable grid, the embodied carbon emissions from its manufacture could wipe out all the savings. The commercial building sector has the tools and experience to lead the way toward a zero-carbon future, but we need more incentives that reduce risk and bring sustained value to property owners to make such a pivot.

2021 Energy Roadmap Competition

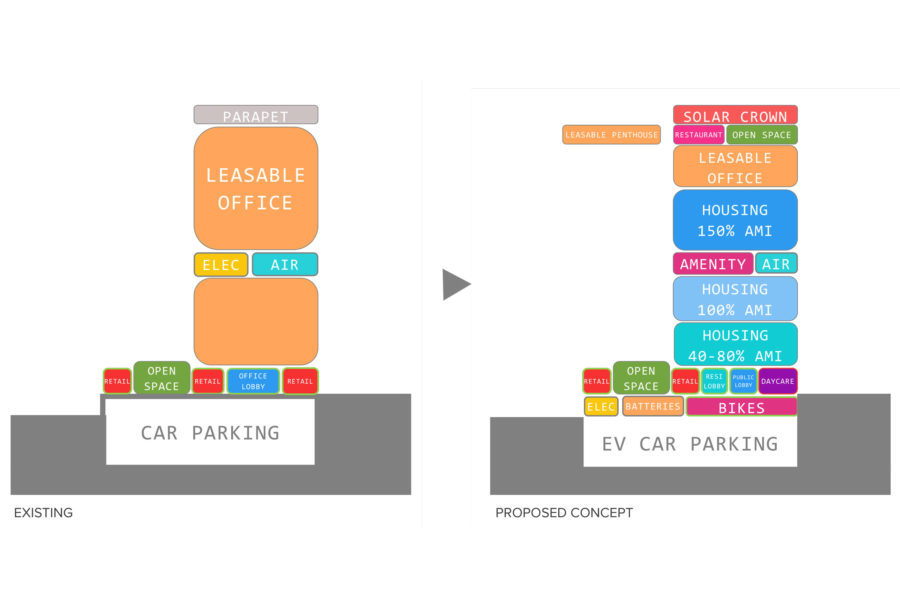

Program considerations in District Carbon were based on downtown zoning code promoting livability and transit-oriented development, including onsite affordable housing, street level use requirements, recreation and rooftop amenities, open space, childcare, bike and EV parking. The proposed concept could be tailored for similar adaptive reuse projects in any city. Image courtesy of ZGF Architects

The Seattle 2030 District launched the “2021 Energy Roadmap” competition to help kick-start these city-level conversations in Seattle, which can be scaled and applied more broadly across the US. While the competition was, according to the district, a “creative exercise for teams to imagine what energy efficiencies could be made in an existing building if there were no implementation restrictions,” it resulted in a comprehensive proposal that reimagines the downtown central business district. In January 2022 the Seattle 2030 District announced that our proposal, District Carbon, had won the inaugural competition.

The 2030 District Network represents a coalition of property owners, managers, developers, tenants, and industry and community stakeholders ZGF has been actively involved with since its founding. The Seattle 2030 District works specifically to make the city and surrounding communities more sustainable while contributing to the region’s environmental resiliency, livability, and affordability.

When the district launched the 2021 Energy Roadmap competition, ZGF, Lease Crutcher Lewis, Stantec, and KPFF saw an opportunity to demonstrate a path to pivot an existing office tower to a mixed-use program with office, multifamily apartments, open space, and retail within a realistic budget and phased construction schedule. The proposed concept provides infrastructure upgrades, modernizes the envelope and structure, optimizes MEP systems, and retools the building program to meet the changing needs of downtown residents.

Importantly, any city planner, building owner, or developer looking to transition to zero carbon could consider the strategies in our proposal. These are just a few examples:

Build integrated teams

- Bring the city, owner, architect, engineer, and builder to the table early for a holistic, integrated approach.

Infrastructure enhancements

- Update power distribution systems and incorporate onsite renewables like PV generation.

- Expand bike storage and EV charging.

Structure and envelope upgrades

- Address both structural and thermal performance to significantly extend the building life and leverage the embodied carbon sunk in the existing building. Saving the existing foundation and superstructure of the tower conservatively kept 15,000 metric tons of carbon out of the sky (this excludes all the emissions from the original sitework).

- Consider a prefabricated facade to reduce the project schedule, structural load, and embodied carbon emissions. This can also meet Passive House standards.

MEP systems

- Optimize mechanical systems to save space, enhance efficiency, ventilation, and accommodate prospective residential conversion. District Carbon’s proposed mechanical design recaptures 60% of space from the existing all air system by upgrading equipment and relocating the electrical room to the garage, providing more usable and rentable area in the building.

- Decouple ventilation from hydronic space heating and cooling. Recover heat from ventilation.

- Utilize a wastewater heat recovery system for domestic hot water needs and a gray water recovery and treatment system for non-potable water demands within the building.

- Use smart building technology to integrate building performance with the human experience. Monitoring and control systems provide a single platform to drive optimization in energy consumption via equipment efficiency, occupancy, and system maintenance, among other benefits.

Transportation

- Proximity to the urban core and co-location of amenities and services can significantly reduce transportation-related emissions. By introducing residential in the building program mix, carbon emissions specifically from commuting to and from downtown could be reduced by nearly 78%.

Solve for Investment, Equity, and Climate

The views from downtown office buildings are some of the best in the city, but only office tenants can enjoy them. District Carbon considers how we can democratize downtown space by making it more accessible. For example, what if the program was flipped to put public amenities and open space on top of the building, rather than the ground floor? Utilizing rooftop decks or mixed-use spaces like bars and restaurant for PV generation serves double-duty by providing shade and screening from the elements. Rendering courtesy of ZGF Architects

While we recognize and appreciate the opportunity the Seattle 2030 District presented to explore these ideas in a “blue sky” scenario, there is real opportunity for district investment across the country. This can take different shapes in response to different climates, energy grids, zoning, building stock, and Covid-related market forces such as vacancy rates.

Adaptive reuse is a winning strategy both for rapid decarbonization and revitalization of our downtowns for equity, safety, mobility, health, and resiliency. There is also room to get creative with programming based on tenant needs. JLL reported, “Investors acquiring hotels for conversion isn’t new, with condominiums, affordable housing, student housing and assisted living long-standing options.”

A study from the National Association of Realtors shows “strong potential for conversion of Class B office units in New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, and Boston” to multifamily housing. There is also opportunity for office properties with high vacancy to reposition as life science labs or jump from class B to class A to stimulate district economies.

Here are some additional strategies to start your district’s zero carbon roadmap.

Become a district! Build public/private coalitions of building owners, developers, city planners, architects, engineers, builders, and contractors to reimagine their own downtown districts.

Calculate the averted embodied carbon emissions from adaptive reuse and reward properties that extend the structural use and life safety of a building (like upgrades for seismic, wind, floods, and subsidence).

Reward early adopters of electrification mandates and energy efficiency measures.

Pilot zoning incentives for adaptive reuse of commercial properties and districts.

Invest in family-friendly district infrastructure with schools, childcare, health care, open green space, and bike/scooter lanes.

Competition team leaders included ZGF’s Marty Brennan and Chris Flint Chatto, Daryl Fonslow at Stantec, Amie Sullivan at KPFF Structural Engineers, and Julianna Plant at Lease Crutcher Lewis