MKThink and HNEI’s findings were surprising in several areas, but maybe most surprising was that the high-performance school buildings rarely operated in their optimal settings. And people were to blame. Photo courtesy of MKThink

Top researchers explain the results of their two-year study of high-performance, pre-fabricated classrooms in Hawaii.

As researchers at MKThink, we’ve been fascinated with the promise of mixed-mode, high-performance buildings, but we have frequently seen their promises fall short.

On paper they make a lot of sense.

When the weather is good, we open the windows, turn on the fans, and rely on natural daylight. When it’s not, we use air-conditioning and turn on the lights. By doing this we’re getting the best of both worlds: high comfort for people while using fewer resources.

However, when we actually study the performance of mixed-mode buildings, we realize the promise is still more of a fascination than a consistent reality. Somewhere between the design of the building and its operation, even with advances in prefabrication enabling tighter controls during construction, we fail to achieve our performance goals. But maybe with each setback we’re understanding a little better the real culprit behind these failures—people.

What is Human Factors Research?

MKThink completed a study on zero energy school platforms in Hawaii in partnership with the US Navy and Hawaii Natural Energy Institute. Photo courtesy of MKThink

The study of people in relation to buildings is called Human Factors (HF) research, and it’s a field focused on using the principles of human psychology and physiology to understand human behavior and performance. It emerged during World War II as a way to better understand how manned systems could be designed to reduce human error and increase human performance. Since then it has evolved into a broader field of study, embedding itself in product companies where human interaction is intimate; recently it has been seen as a key to solving many of the issues with underperforming buildings.

Over the past decade we’ve been funded by the Hawaii Natural Energy Institute (HNEI) and the Office of Naval Research (ONR) to better understand the relationship between human factors and environments, both natural and man-made. We’ve worked on a variety of projects together across the Asia Pacific in both military and civilian settings. In 2014 we embarked on an effort with HNEI to study high-performance, prefabricated classrooms in Hawaii and compare their energy and comfort performance to traditional classrooms.

The Latest Study

MKThink completed a study on zero energy school platforms in Hawaii in partnership with the US Navy and Hawaii Natural Energy Institute. Photo courtesy of MKThink

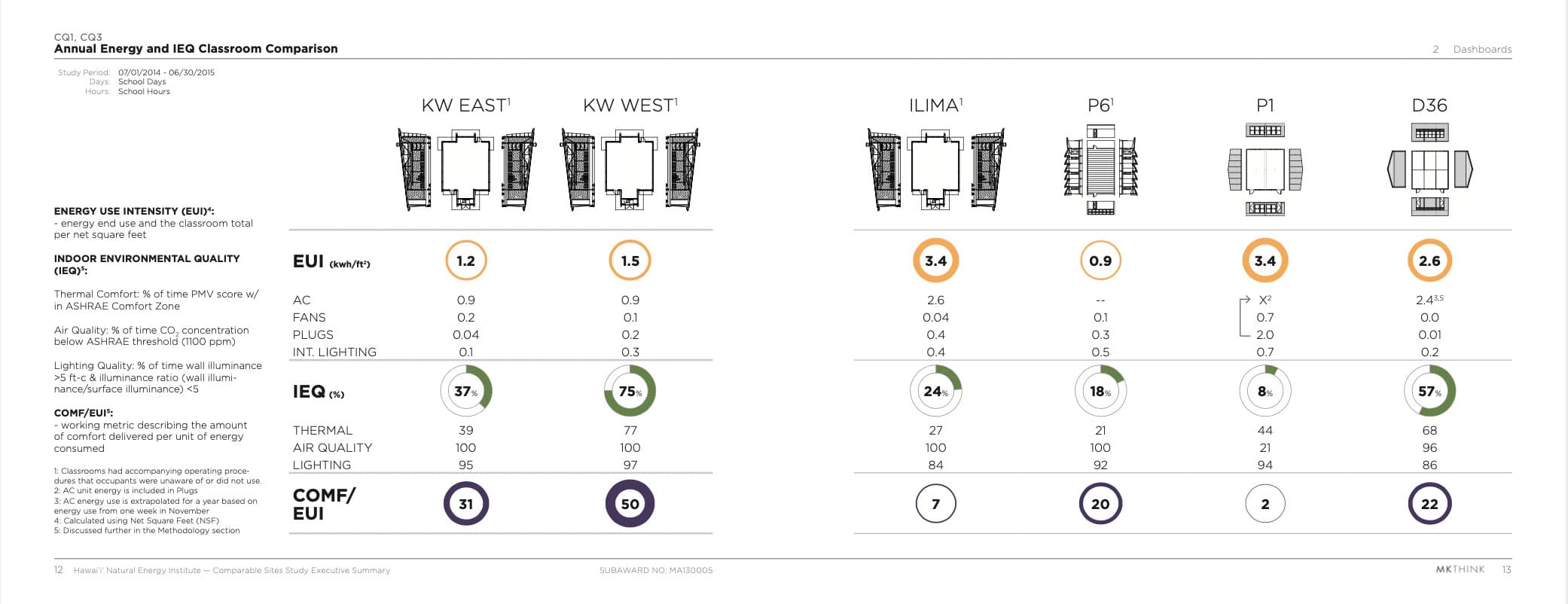

As part of this study we outfitted four high-performance and two traditional classrooms with 227 sensors, measuring everything from energy use by building system to indoor environmental quality (IEQ) variables like thermal comfort, air quality, and lighting quality as well as when windows were open or closed.

The Results

MKThink and HNEI (Hawaii Natural Energy Institute) studied five Hawaiian classrooms for energy and comfort/health performance over two years. Photo courtesy of MKThink

The results of the latest study revealed that the high-performance classrooms consumed more energy and were less comfortable than predicted. While they did outperform the traditional classrooms by using 40% less energy per square foot (EUI), on average, and having a higher IEQ 6% of the time, they underperformed against expectations using 50% more air conditioning (in 2 of 3 classrooms) than modeled, 70% more active lighting than needed during school hours, and spending less than 40% of the time in the IEQ comfort zone.

To make matters worse, 60 to 85% of the air-conditioning use was during times when the conditions were such that air-conditioning didn’t need to be used, as passive ventilation techniques could have effectively achieved the set points.

The analysis later showed that many of these systems were actively turned on by the users, overriding the system schedule and going against the design intent. It was the people who interfered with the high-performance operation of the spaces.

Why Did This Happen?

The problem revealed during this study, and reinforced by projects we’ve encountered in Guam, Philippines, Hawaii, and elsewhere, is buildings aren’t operated like they were designed. One hypothesis for that is that it’s much easier to operate a building in active mode, where you can “set it and forget it,” often with one set of controls, but to use passive mode the users have to do their own mental calculus, figuring out if the conditions are right to open the windows and turn on the fans. Then they have to adjust each of those systems or devices individually. That’s a tall order amidst a busy schedule. And that’s likely why we often see buildings operating in active mode even when the conditions change and the building settings make the buildings uncomfortable. Ever been in an air-conditioned building and needed a coat? It’s likely because it’s easier to leave the systems running and tolerate some discomfort instead of go through the hassle of making any changes.

What Do We Do About It?

The future of high-performance buildings requires a deeper focus on how people actually use buildings, not just how the buildings are designed to be used. It requires both Human Factors research techniques to understand the why behind the behaviors as well as the actual behavior data to connect the dots and support the conclusions that can change design decisions. That’s why we’re now working to advance the use of computer vision technology to objectively measure how people move through and use spaces. We hope this information will start to connect those dots and close the gap between actual and designed performance, bringing us closer to a future that’s more reality than fascination.

Signo Uddenberg, MKThink

This article was written by Signo Jesse Uddenberg and Mark R. Miller, principal investigator, with collaboration from Richard Rocheleau, director at HNEI, and James Maskrey, associate specialist in energy efficiency at HNEI. Uddenberg is a director in innovation and R&D at MKThink. With a background in sustainable engineering and human-centered design, Uddenberg brings technical expertise to projects intersecting human behavior and the environment. HNEI’s mission is to help guide Hawaii through its clean energy transformation by focusing on cost effective and practical solutions to help deliver commercially viable renewable energy for Hawaii and the world.