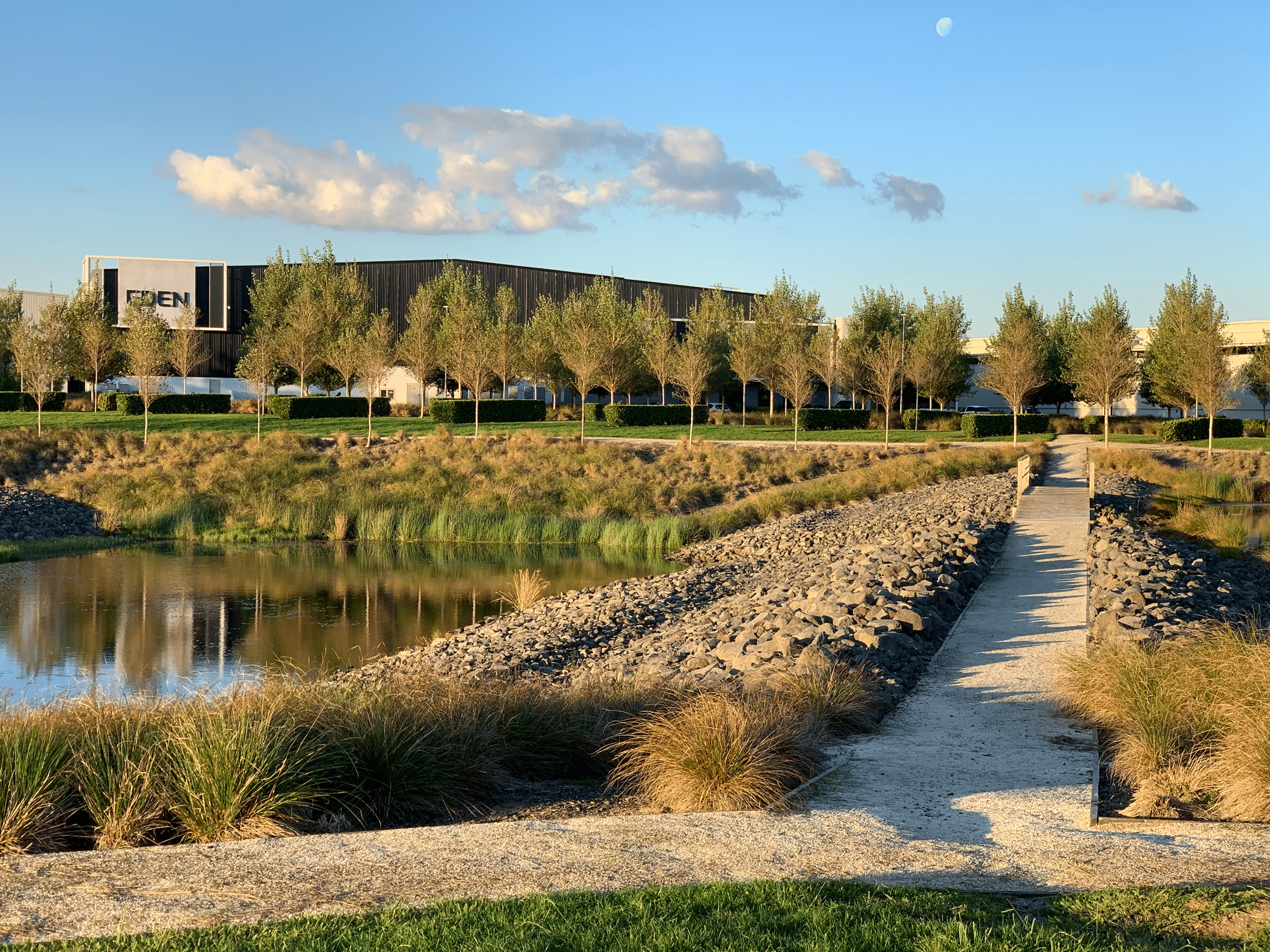

Materials reuse was a primary design mandate. The berms were created with fill dirt from site grading. Native materials and traditional New Zealand gardening practices influence the landforms and plantings and make the landscape distinctive from land and air. Photo by Blake Marvin

Auckland’s environmental approach offsets airport expansion with identity-expanding greenspaces.

Auckland International Airport (AKL) has a refreshingly progressive approach to industrial expansion. Airport management prioritized an environmentally conscious identity for the country via AKL, which forms the first impression of New Zealand for 75% of its visitors. The airport is on Manukau Harbor and is one of many ecologically sensitive waterfront projects Surfacedesign has been fortunate to design. The firm was invited to speak on waterfront biophilia at the Expedia Campus at Greenbuild 2020.

New Zealand’s agricultural heritage has sustained the country. Appropriately, AKL management wanted to responsibly balance runway expansion and related industrial development with planned greenspaces. The landscape architecture evolved from consulting on a business park project into collaborating on an urban design for AKL’s six square miles of property for ongoing ecological improvements through 2044.

See Also: This Impressive Airport Design Changes the Way You Travel

For sustainability and budgetary reasons, material reuse was an underlying mandate. Other primary priorities were stormwater management, new roads that maximize safety and efficiency for large delivery trucks, and local materials sourcing to minimize the project’s carbon footprint. Then our placemaking mantra—“Incorporate local topographical and cultural references into the design”—was applied so visitors and residents alike would intuitively recognize a sense of place.

Local design inspirations are abundant. Auckland’s stunning landscapes combine natural volcanic and coastal topography with distinctive agrarian land-use traditions. Dating back several centuries, Maori settlers built stonefields to protect imported Polynesian plants from the harsher Kiwi weather. In the 1800s, European immigrants planted hedgerows and orchards to create natural windbreaks, improving crop yields.

Get the right input and feedback.

Infrastructure for The Landing Business Park focuses on efficient road design between the complex and AKL (background) plus stormwater management. The remediation ponds flow into Oruarangi Creek (lower right), which feeds Manukau Harbour (top). Photo by Blake Marvin

One of the project’s first phases is an AKL-adjacent business park called The Landing on 250 acres of airport-owned property. The normal utilitarian industrial-complex approach—large warehouses with small offices in rectangular buildings separated by gridded streets—was re-imagined into an environment that better serves the employees while also satisfying the city and the neighbors. Significant about this development is its proximity to Oruarangi Creek, where the first Maori canoes landed in New Zealand from Polynesia. We developed a Landing & Lift-Off theme to acknowledge the complex’s location between the early humans landing in the country and the constant lift-offs at AKL.

Maori input informed The Landing’s landforms and infrastructure. Through participating in meetings and ceremonies with the Maori (who still inhabit the original village in New Zealand, not far from AKL), we gained insights into the local ecology. As development encroached in the 1950s, Oruarangi Creek was cut off to build a treatment plant. Sewage was pumped into the water, the creek became barren, and diseases metastasized in the tribe. The Maori explained that the creek could no longer flush and that sediment accumulated in the runoff channels. The sewage plant was removed in the 1990s.

To prevent history from repeating itself, The Landing’s stormwater infrastructure exemplifies the over-arching AKL approach to remediation. All runoff is channeled into planned rain gardens—planted in center medians and along the sidewalks—or into retention ponds.

The ancient Maori waiorou filtration philosophy that water should always pass through rocks before entering a larger body was incorporated into The Landing’s plan. In addition to embankment riprap surrounding the two ponds, Maori-inspired gabions were added around the drainage pipes. Plant growth obscures the gabions’ cages. Pond plantings’ root systems help remove toxins.

The Landing’s new landforms functionally repurpose graded dirt on the jobsite instead of trucking it to a landfill. Nearby Maori stonefields served as inspiration for mounds in the roundabouts and along the streets. An added benefit was mitigating the “visual pollution” of traffic and parked cars by drawing attention to the landscape. The V-shaped plantings and parking lot layouts are influenced by bird flight, significant in the Maori culture. These patterns also reference architectural herringbone hedgerows from European immigrants’ planting practices and the chevrons painted on airport runways.

Take good design out to the streets.

Runoff is channeled into rain gardens comprising drought-tolerant native grasses. Local volcanic rock was added to the concrete mix for The Landing’s curbs and sidewalk pavers. Photo by Blake Marvin

Street design is another example of integrating local influences into a function-first aspect of the project. Layout minimizes the carbon footprint by optimizing pavement routing between The Landing and AKL. Further, we learned from other urban design projects that placing the street closer to the buildings slows traffic, increasing safety. Curves and roundabouts were sized with large delivery trucks in mind.

Shop local.

The project’s primary stormwater pond, across the street from AKL’s retail district, is part ecological intervention and part artistic amenity. Known as the Auckland Airport Sculpture Park and Walk, this curated landscape combines habitat-attracting groundcover plantings, a corridor of trees to lead birds away from the runways, and trails that meander past sculptures by prominent New Zealand artists. Photo by Blake Marvin

For performance and aesthetics, custom concrete for the curbs and pavers was created using local aggregates. Recycled volcanic rock was used in the mix to cost-effectively add a dark tint, helping hide dirt that accumulates in curbs’ shadow lines. Local experts tested and determined appropriate thicknesses for curbs and sidewalks as well as the optimal surface-grinding process to expose the distinctive aggregate. Curb edges were radiused for aesthetic reasons. Once installed, they proved more chip-resistant to truck impacts than normal 90-degree edges. Additional hardscape uses local basalt (formed when lava flows into wetlands), supplemented by other rocks available from nearby quarries.

The planting plan is grounded in drought-tolerant native species, supplemented by culturally endemic ones. Parking orchards were created to balance the “death by asphalt” heat-island effect. Poplars, London plane, and native pohutukawa trees cast dense-canopy pavement shade, minimizing radiant heat. At an AKL employee parking lot closer to the terminal, we developed 10×10-foot tree boxes to make the pavement less hostile, basically launching an onsite nursery. The boxes create forklift-optimizable shade and will be moved to other locations as the airport evolves.

Keep going.

Other project phases continue AKL’s sustainability mission. Additional graded dirt from ongoing growth at The Landing is being used to shape landforms at the nearby Oruarangi Creek Public Open Space, a waterfront park that will incorporate the country-long National Bike Trail. Further, mature pohutukawa trees in the path of runway expansion were transplanted to Abbeville Estate, a wedding and event venue near the airport. (The preservation project also involved relocating two heritage buildings to the estate.) Additional plantings create wildlife habitats. Most notable is a corridor of trees along an esplanade that connects AKL’s retail district to Abbeville Estate and the Airport Sculpture Park and Walk. It attracts birds away from the runways.

Celebrate efficient construction.

An unexpected green benefit of the AKL project is construction efficiency. The contractors initially questioned the visible-from-the-air geometric designs. Once they understood the culture-based thought process, they accepted the creative challenge. Workers measured layouts multiple times, eliminating waste and re-dos. An uplifting anecdote emerged during an early stage of construction. A homeless man approached the hardscape crew and said, “That’s interesting; I can do that.” Several years later, he is one of the contractor’s lead field foremen, providing for his family.

Thus far, AKL’s landscape projects are under budget and on schedule, thanks to the building team’s front-loaded attention to detail—it’s a source of pride that airport visitors can see the work from the street and the air. An unexpected sign of success is that local residents now come to The Landing on weekends, using the complex as a staging area to enjoy the network of bike and pedestrian paths.

The AKL development project is an ongoing exercise in sustainability of both resources and culture. The underlying landscape design language—Maori stonefields and European orchards and hedgerows—will connect each phase, from AKL’s terminal plaza up to Oruarangi Creek Public Open Space. AKL’s planned placemaking demonstrates the airport’s commitment to balancing future development with environmental design rooted in the local history and culture—a tribute to prior landings and future lift-offs.

James A. Lord is a cofounding partner of Surfacedesign. A USC-trained architect, Lord pursued landscape architecture at Harvard GSD after a front-row seat to the Los Angeles Riots convinced him that built environments can heal social ills. His work combines local influences and materials to create inspiring spaces. The firm won the 2017 Cooper Hewitt (Smithsonian Museum) National Design Award for Landscape Architecture.

James A. Lord is a cofounding partner of Surfacedesign. A USC-trained architect, Lord pursued landscape architecture at Harvard GSD after a front-row seat to the Los Angeles Riots convinced him that built environments can heal social ills. His work combines local influences and materials to create inspiring spaces. The firm won the 2017 Cooper Hewitt (Smithsonian Museum) National Design Award for Landscape Architecture.

Tim Kirby is a principal at Surfacedesign, leading many of the firm’s large public-space projects. He uses all available technological tools to design and execute landscapes that combine social meaning and emotional allure. His ultimate goal is to influence positive environmental change while offering people a sense of respite and connection through well-conceived design and implementation.

Tim Kirby is a principal at Surfacedesign, leading many of the firm’s large public-space projects. He uses all available technological tools to design and execute landscapes that combine social meaning and emotional allure. His ultimate goal is to influence positive environmental change while offering people a sense of respite and connection through well-conceived design and implementation.