Story at a glance:

- This feature takes the guesswork out of achieving an impact-resistant building envelope.

- We look at how to achieve peak performance as well as the right level of protection against natural and man-made disasters.

Rarely do we as architects, contractors, and builders have our buildings’ structural integrity tested the way it has been over the past several years. In 2019 damage exceeded $136 billion, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Weather patterns and the hurricanes they produce have always fluctuated in long cycles—very active seasons followed by long periods with mild hurricane seasons. While the number and intensity of storms vary over a period of years, scientists have predicted based on the past three decades that there is likely to be an increase in the number of active storms per year. Scientists also have reason to believe that future storms may be more intense, lasting longer after they make landfall.

This activity can lead to increased destruction, particularly in low-lying areas, where population density continues to grow. It is important that we fully understand evolving building codes so we can take the guesswork out of achieving an impact-resistant building envelope, achieving the right performance to protect buildings and the occupants that inhabit them.

Building Codes and Impact Products

Texas State Aquarium in Corpus Christi, using YKK AP 35H. Photo courtesy of YKK AP

On Aug. 24, 1992, Category 5 Hurricane Andrew struck the state of Florida with 175-mile-per-hour winds, devastating Miami. It was one of the most destructive US hurricanes to date, next to 2017’s Hurricane Irma, and its legacy also lives on in the way it permanently changed Florida’s building code.

Prior to Andrew, there were more than 400 code jurisdictions in the state of Florida. The storm exposed the code’s crucial faults and an overwhelming lack of code enforcement. Miami-Dade County was the first to implement hurricane impact and cyclic pressure testing in the mid-1990s, as mandated in the South Florida Building Code (these standards are now TAS 201 and 203). A critical step was then taken in 2002, when the first statewide building code took effect. The newly consolidated International Building Code was adopted as the base code and all jurisdictions in the state were required to enforce the new code as a minimum. With introduction of the new statewide code, the South Florida Building Code was retired. However, the newly formed Florida Building Commission acknowledged the stringent nature of the South Florida Building Code and created the High Velocity Hurricane Zone (HVHZ) within the Florida Building Code.

Today the HVHZ is defined as Miami-Dade and Broward counties. Requirements for the HVHZ are more stringent than those required for a statewide product approval. The Florida legislature has mandated a code update every three years.

Since the mid to late ’90s, the objective of impact products has been to protect the building envelope from rapid internal pressurization. In 2004, when Hurricanes Charley, Ivan, Frances. and Jeanne all hit the state of Florida, updated codes and impact products were put to the test, but it wasn’t until Hurricane Irma in 2017 that a storm comparable to Andrew tested the strength of buildings built to comply with 2002 codes.

“As an industry, if we look back at the past two decades, impact products have done an excellent job of protecting the building envelope from potentially detrimental consequences, like damage to or full loss of a building’s roof,” says Barry Wampler, Orlando branch manager for YKK AP America. “During the 2004 active hurricane season there were minor instances in which aluminum materials were slightly overstressed, but on a whole, impact products continue to successfully perform.”

Mitigating Water Intrusion

John’s Hopkins All Children’s Hospital in St. Petersburg, Florida, using YKK AP 50H. Photo courtesy of YKK AP

Building codes have successfully improved the structural integrity of buildings, given the inclusion of impact-resistant products. However, water intrusion is an issue that continues to surface. Prior to 2002 water intrusion was not an issue if the building structure itself wasn’t able to survive high and sustaining winds. Now that buildings are built to meet and in many cases exceed codes, severe wind-driven rain and heavy flooding have become an increasing challenge.

The speed of a storm can determine the amount of rain a region will experience. In general, fast-moving storms produce less rain, and the resulting water damage can be relatively minimal. On the contrary, storms like Hurricane Florence in 2018 and Tropical Storm Imelda in 2019 can move slowly, dropping significant amounts of rain and causing flash flooding.

When Hurricane Florence, for example, slowly made its way through the Carolinas at a pace of 2 to 3 miles per hour, it set more than 28 flood records, according to a US Geological Survey.

Forensic research after the 2004 and 2005 hurricane seasons led to a greater understanding of severe wind-driven rain by 2010, but most of this learning has not worked into the codes yet. Moreover, building activity continues to take place within the Federal Emergency Management Association, or FEMA’s 100-year floodplain, and buildings that are built above or outside of the 100-year floodplain are still susceptible to flooding.

Windows and doors are critical to helping prevent water intrusion in a building, however even when built to meet and in some cases, exceed state building codes, they are not a guarantee. “In tropical storms and hurricane wind-driven rain conditions, the product selected to meet the state and local code requirements may still experience water leakage because these extraordinary conditions exceed the rated/code requirements for water penetration,” according to the American Architectural Manufacturers Association. While improvements have been made in reducing water intrusion from wind-driven rain, it is important to get back into each building quickly after the storm to dry out the interior.

Danger from rising water due to storm surge or flooding is a separate issue than wind-driven rain and can be difficult to prevent. It is best staved off by elevating functional areas above predicted flood and wave action levels or by building outside the floodplain. Existing buildings located inside or below the floodplain pose a dual challenge, especially in areas prone to flash flooding.

The Importance of Making an Entrance

The Cici and Hyatt Brown Museum of Art in Daytona Beach. Photo courtesy of Museum of Arts & Sciences in Daytona Beach

Commercial entrances are particularly vulnerable to water intrusion. Typically commercial entrances must meet the Americans with Disabilities Act Emergency Egress requirements, which requires an unobstructed path to exit a building or structure. However, commercial entrances are exempt from water test requirements, which can be problematic when dealing with severe weather conditions. While a building may have been built to meet and even exceed the strong winds from hurricanes, if the entrance is not taken into consideration in the design and execution of the project, water intrusion may still occur.

One way to better protect commercial entrances from water intrusion is to consider a roof or entrance overhang. Overhangs are well known for their energy savings properties, as they effectively reduce solar heat gain by providing additional shade. However, they can also keep wind-driven rain from entering the entrances and windows of a building. Overhangs help keep rain away from windows, entrances, and the foundation of the building envelope, reducing overall water pressure.

The Cici and Hyatt Brown Museum of Art in Daytona Beach is a great example of this. The museum opened to the public in 2015 and serves as a sanctuary for local residents and a destination for visitors interested in exploring Florida history. The museum displays more than 2,600 pieces of art that are a nod to old Florida with scenes of towns, animals, and landscapes dating back to the 1700s. RLF Architects designed the building, which was built to resemble an old, rural Florida home and reflect the rich history of the artwork housed there.

Hurricane-resistance was a key component in the design process and impact-resistant products were used throughout the building. YKK AP’s YHS 50 TU impact-resistant storefront, YHC 300 OG impact-resistant curtain wall, and Model 35 H impact-resistant entrances were used on the building. An overhang was also integrated to add to the character of the building and provide additional protection from wind-driven rain.

When Hurricane Irma hit in 2017, the museum served as a shelter for staff who needed to stay on property and those who weren’t able to leave town. Despite nearly seven inches of rain combined with up to 60 to 80-mile-per-hour wind gusts, the building resisted flooding and damage thanks to the thoughtful design of the building—a feat compared to other areas of Daytona Beach.

Even overhangs may not be enough to prevent water intrusion from severe wind-driven rain during a hurricane. Another consideration when designing the entrance of a building is to utilize hard surface floors and properly equip the interior of the entrance with strategically placed drains. Ideally this type of drainage will be coupled with an entrance awning or overhang for maximum protection for wind-driven rain.

Rising water from flash flooding or water pooling in low lying areas is a life-safety concern for entrances and the fenestration around them. The rate-of-rise of floodwaters for an at-risk site needs to be determined and paired with adequate warning time to allow evacuation of the building. Specialty flood doors may be used to hold back rising flood waters and keep the path of egress open for the required warning period.

Wet-glazed vs. Dry-glazed

- Wet-glazing, shown with IGU. Image courtesy of YKK AP America

- Dry glazing, shown with monolithic. Image courtesy of YKK AP America

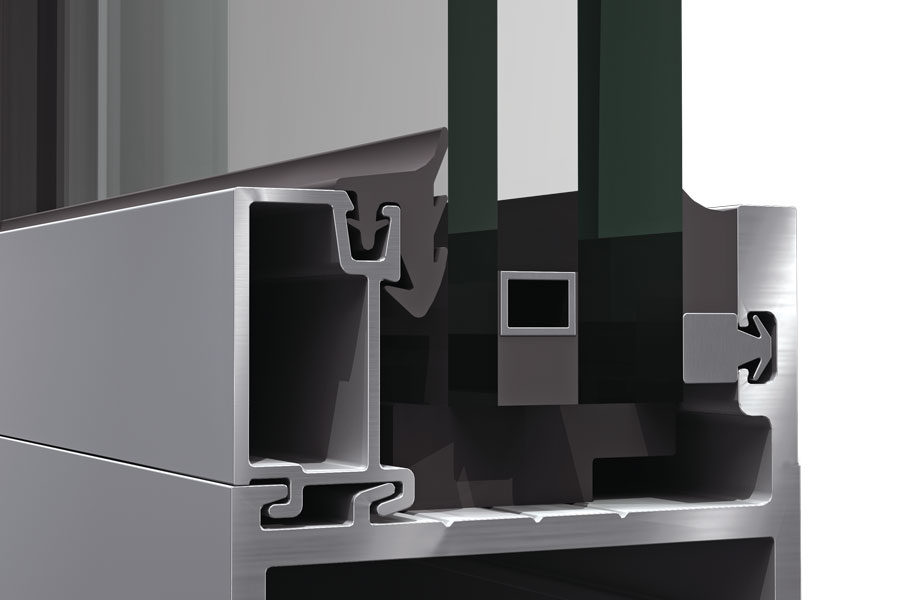

Glass itself is resistant to water penetration but being knowledgeable about the difference glazing can make is important. Wet-glazing secures the glass with a wet seal or compound (typically silicone) over a backer rod or glazing tape, while dry-glazing secures the glass with a dry, pre-formed resilient gasket. Prior to the 1990s the traditional way to protect window and door openings was to use some type of shutters.

The first generation of hurricane impact-resistant windows and doors were wet-glazed because that was the only way to pass the newly developed impact and cyclic pressure testing. However, over time product designs and new interlayer materials were introduced. Hurricane, impact-resistant dry-glazed systems are now commercially available and have established their own successful track record of performance during hurricanes.

Each glazing method has its proponents. Dry-glazing is less costly, in part because it is easier to install. It is also the method of choice for small missile glazing. Even though laminated glass protects the building envelope, it can break from debris impact. Dry-glazing is much easier to reglaze.

Wet-glazing is more costly and requires greater skill. If wet-glazing is done in the field, adverse weather can either delay application or degrade the seal. It does, however, allow using less costly interlayers such as PVB that deflects under loading. If installed properly, wet-glazing provides very good structural integrity and water penetration resistance.

A Work in Progress

Rowing Tower in Bradenton, Florida, using YKK AP 50H. Photo by Ryan Gamma Photography

Since Hurricane Andrew hit in the ’90s the building industry has come a long way in recognizing that codes must evolve to better protect buildings themselves, major sources of property loss, and, most importantly, building occupants.

The International Building Code is now the base code for all states and is updated every three years to reflect new learning and knowledge, with the seventh edition of the Florida Building Code in effect as of Dec. 31, 2020. Forensic research after an active hurricane season provides the best data on what past measures were successful and where more attention is needed. And while our industry has come a long way, there is always more work to be done.

Additionally, rising water from storm surge and short duration over-saturation are areas that need continued technological advancement, and we will likely see more developments over the coming years.