Story at a glance:

- Conversations about workplace interiors and furniture are evolving as demand for sustainable solutions is on the rise.

- Architects and manufacturers alike share their expert perspectives on what it takes to make workplace designs that last.

The modern office should feel timeless. It shouldn’t depend on trends, and it certainly shouldn’t lean on trends without considering what the people working in an office actually need and how they work. At least, that’s what some top experts across architecture and manufacturing say.

“We do a little bit of a disservice for ourselves when we follow too many of the trends instead of really talking to the people,” says Neil Schneider, who leads HOK’s interior design practice in Chicago.

This summer Schneider and his team were working to fix a space designed by another firm because the previous firm designed based on trends, complete with lounge furniture all over. While the project was beautiful, he says the employees found it difficult to work in. “We’re ripping out 30% of it because somebody didn’t have the dialogue about what really works. They followed a trend. That’s hard because they spent a lot of money as a company.”

Many manufacturers are rethinking designing for trends, focusing more on asking the right questions at the right times of the right people. “You can’t, as a design department within an organization like this, respond to what sales are asking for as a reactionary response,” says Lee Fletcher, vice president of product design at Canada-based Three H Furniture. “You need to ask, ‘Why are people asking for that thing?’ That defines the problem with which you try to find a solution that’s appropriate for the environment you’re in.”

Fletcher has been in the industry for 25 years. As an industrial designer he worked at many of the top furniture companies before starting an independent design studio working in contract office furniture. Years later, after working for Three H independently, he joined Three H full-time, where he’s been since January 2024. “I’m very compelled with the systems nature of furniture—that it’s not just a static object; it’s an object that needs to do a lot of things for a lot of people,” Fletcher says.

The Office is Evolving

Collections like Harris, launched in November by Three H Furniture, offer lockers and related pieces with an underlying grid system. Rendering by SEEN CGI, courtesy of Three H Furniture

Modern office needs are ever-changing, and furniture has a big role to play, which is exciting, Fletcher says.

“When I started it was all about panels. It was all about cubicles.” One company he previously worked for used to measure its success by the number of panels it ran through the plants each week. “Now it’s a very different environment filled with all kinds of settings and contexts and requirements.”

Today he feels fortunate that his work revolves around developing products that respond to the changing needs of human behavior and supporting work. “I heard someone say once that one of the great privileges of a designer is to be able to solve problems,” he says. “I feel a little bit like that here, that there’s a never-ending stream of interesting problems to solve. For a designer it’s a great industry to work in.”

Fletcher says flexible workspaces are in demand as the hybrid office evolves and more people return to work, but how we define flexibility is changing. Schneider has similar ideas, saying flexibility is more about the people than the objects. “Flexibility is more moving into the movement of individuals between different spaces based off of purpose,” Schneider says, pointing to the need for different types of spaces depending on focused or collaborative work, for example. “Flexibility is more about movement and agility.”

Schneider points to a new book by HOK’s Kay Sargent, called Designing Neuroinclusive Spaces, that looks at how creating spaces that work for neurodivergent people helps everyone thrive. The book explores the design of spaces for different kinds of engagements, depending on energy levels, needs, and level of activity, as well as the need for strategic spatial planning and attention to colors, lighting, and sound. “There’s a lot on how we do that and giving people that choice to move throughout the day, or, for example, I like to be in the sunlight so I’m going to go sit over here because I’m more productive here. That’s where we’re seeing flexibility happening,” Schneider says.

There needs to be a level of flexibility and the ability to do this one day and that the next day.

Previous talk of making spaces feel “more like home” is evolving, too. “There needs to be a level of flexibility and the ability to do this one day and that the next day,” Fletcher says. When it comes to furniture, he says demand isn’t so much about bringing in particular wood tones and fabrics, but more focused on considering what makes a living room inviting in the first place. “You generally don’t have one piece of furniture connected to another piece of furniture in your house, right? It’s discrete pieces. You can move them around, and each one has a story because they came from different places, and yet you’ve curated that so it hangs together. It’s a continued evolution of that, with the constant thread of—this is not your home; it’s a public space, so it needs to be durable, and it needs to have a certain measure of sophistication, and marrying all that together.”

HOK’s Chicago team recently relocated to a new, 26,000-square-foot studio in the heart of downtown Chicago. The new office celebrates all things timeless, repurposing furniture from years past, with classic colors and neutral fabrics alongside exposed columns and large windows, and avoiding any wild patterns or trendy shapes. “Even though we have pops of color there are no crazy patterns that you’re going to see and be like, ‘Oh, that was 1972, or those are the octagonal patterns that were around in the ’90s,” Schneider says.

Sometimes the simplest solutions are the best. His personal opinion? “A table is a table is a table,” he says, patting a basic wooden table near his workstation. “This round table is the same as a round table from probably the 1700s. Does it hold my stuff? Does it work? Is it right for what people are doing?”

He cautions against conference rooms filled with beanbag chairs that no one will use. “If it’s a basic, like a black dress, it’s going to work in any office, and it’s going to last,” Schneider says, adding that a few pops of color can be fine, but furniture needs to be purposefully designed for what people need to do.

Design for the Environment

The Kynde table launched in 2024 as a flexible and sustainable solution, with lightweight 3D Techknit as its base. Rendering by SEEN CGI, courtesy of Three H Furniture

In general Three H also looks at flexibility through the lens of movement, as its designs create spaces that allow people to easily move around them. “That’s why there’s integrated seating; it can be accessed from two sides,” Fletcher says.

He calls it micro architecture, and the use of laminate allows designers to bring wood textures and colors together to add warmth. “It creates these environments without shouting its presence. There’s a quiet confidence.” Great furniture supports you without you noticing, he says.

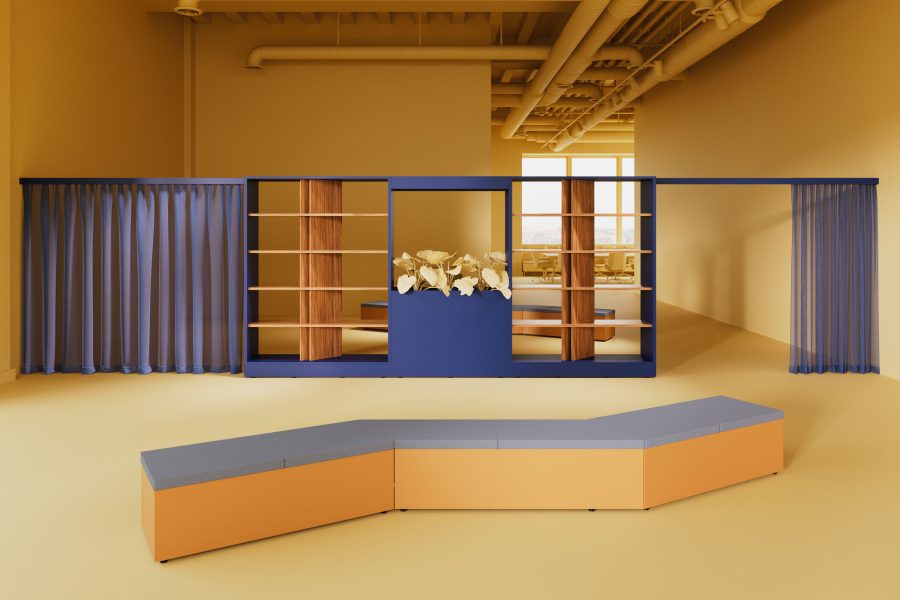

Three H’s latest furniture collections look at meeting needs in multiple ways, with clean, classic looks that fit most anywhere. Harris lockers serve as a touchpoint for the beginning and end of employees’ days, while Sutton is a zoning system that shapes the space in between.

“We’re creating the backdrop for great workplaces to happen in,” Fletcher says. “We’re creating the environments. A lot of our dealers will have a soft seating line as well as us, so we’re creating environments where soft seating collections can be integrated with what we’re doing. We’re creating environments that are sympathetic to other kinds of spaces. That’s what Sutton is about. It’s the kind of thing you don’t necessarily immediately recognize as a discrete product, but it’s creating a space for things to happen in.”

Three H is focused on continuing to develop a “kit of parts” with its furniture pieces. “Those can be put together and look tailored, like millwork. Even though it’s not millwork and these are discrete, separate pieces, we are trying to develop discrete pieces that can be used alone as well as together,” Fletcher says.

We’re creating the backdrop for great workplaces to happen in.

Most of the physical mass of products that come out of Three H’s plant are particle boards, Fletcher says, and most have a lot of recycled content. The company is also increasingly looking at how products can be refurbished and repaired easily to prolong their lives. Fletcher says they are continually working to reduce the number of materials within a given product to make it more recyclable. One example is their Kynde table, launched in 2024 as a flexible and sustainable solution that will be at home in offices for many years to come. It has no “head of the table” and is designed to meet evolving aesthetic needs, with options ranging from knit fabrics to classic laminates.

“One of the things we did with the base on our Kynde table is make sure it was one resin type. It has elastic, it’s got some flex in it, but that’s more to do with the way it’s knitted, not elastomerics in the yarn. There is one resin type in the yarn, even though we’ve got two colors. Trying to do things like that I think will help a lot,” Fletcher says.

Kynde is a robust structure without being heavy, he says. The base’s 3D Techknit is lightweight and flexible, and if someone wants to update the look and feel of the table in the future, the table allows them to do that without being materially intensive. “It’s not going to cost a lot, and the majority of it will stay in service. We’re trying to build compositions that have those characteristics that will prolong the product line, building in a lot of reconfigurability and not gluing things together, not screwing things through faces, so when these products get separated it can be redeployed in other ways and refreshed in appropriate ways so the product life will continue,” Fletcher says.

Reducing metal inserts in particle boards is also important. “That’s not easy to recycle because the steel gums up in the machine. If you can configure the product so it doesn’t require those steel inserts, it becomes easier to recycle,” Fletcher says.

Collections like Harris, launched in November, offer lockers and related pieces with an underlying grid system, which Fletcher says all products going forward will have, for an increased ability to mix and match. “It will allow you to redeploy things in different places without having to worry about, ‘Will this fit with that?’ At a product level this is a sustainability strategy as well.”

Three H’s research found a lot of people use lockers as space division, but people don’t always want solid volumes. The Sutton Collection flexible zoning solution was born out of a need for space division without making people feel disconnected.

“By adhering to certain datum lines, we can create benching and shelving units and, even if they’re from different product lines, they all line up,” Fletcher says. Design teams can create taller spaces for more privacy and space division, or choose to keep an area low and open to encourage collaboration. They can integrate lockers in a more public area with seating, or they can separate those out, based on needs. “There’s this ability to create different environments.

They’re a little more accessible, they’re a little more approachable, and they’re also quite flexible to respond to different kinds of environments, whether it’s office spaces or more casual spaces. They all work together for that.”

The Future of Office Furniture

Three H’s research found a lot of people use lockers as space division, but people don’t always want solid volumes. Rendering by SEEN CGI, courtesy of Three H Furniture

Harris lockers serve as a touchpoint for the beginning and end of employees’ days. Rendering by SEEN CGI, courtesy of Three H Furniture

When Three H launched its Hudson line in 2025 there was a big push for private offices. “Twelve months later it’s not quite the same. It might be in part because there’s an increasing groundswell of people coming back to the office, and not everyone can have a private office. So how that all evolves, it still feels like it’s in flux,” Fletcher says.

He expects the furniture of the future will increasingly be designed to work alone, together, or in any number of configurations. “It might start as a benching product, but it could be separated to be in a private office or separate workstations,” he says. “I suspect there’ll be a mix of those kinds of things—products that are more flexible. I would anticipate more sophisticated ways of that happening.”

He also hopes to see decommissioning become a more integral part of the design conversation, answering, “What happens when furniture is coming out of a space?” “Whether it’s our furniture or someone else’s, that is going to change how we work. It’ll change the revenue stream, it’ll change how we develop products, and it’ll change what I do in ways I’m really looking forward to.”

The biggest thing, though, is that it must be usable. And to be usable, it must look good, and it must last. “I often say no one cares how sustainable a product is if they don’t want the product,” Fletcher says. “You need to constantly develop useful, beautiful, elegant, durable, everyday things people want to use and create environments people want to be in.”

He says companies like Emeco, Humanscale, and Andreu World also do amazing work in this area, and there’s room for everyone to get on board. “We’re all going to do it in our own way. If I’ve learned one thing about sustainability and life cycle analysis, it’s very contextual. What’s right for you in one context is going to be very different from someone else in another context, whether you use aluminum or wood or whatever, based on a whole host of factors. We’re all going to have different ways of doing it, and I think that’s really exciting.”