Conditions

The uniformity of the Great Plains is what lends to their subtle beauty. The dynamic, climatological complexity native to the Midwest isn’t represented by its visual parity. In other words, it looks boring—but it’s not.

The area around Neosho, Missouri, experiences a four-season humid continental climate, like much of the surrounding area, and it’s also situated at the heart of ‘Tornado Alley,’ a multistate junction where divergent wind patterns from the Rocky Mountains, the Sonoran Desert, and the Gulf of Mexico collide. While this creates powerful and dangerous tornadoes, it also leads to necessary developments in education, safety, and energy research, all of which are vital to be able to respond to climate change in and beyond the Midwest.

Originally barely a blip, in 1984 Crowder College put Neosho on the map for good. A research team at Crowder became the first to design, build, and drive a solar-powered vehicle across the United States, and since then, Crowder has consistently won or placed in various international solar and alternative-fuel competitions, beating even top-tier universities from around the world.

Capitalizing on the success of its programs and its designation as Missouri’s premier energy-education center, in 2002 Crowder began the first phase of construction on a 27,000-square-foot, LEED Platinum headquarters for its Missouri Alternative and Renewable Energy Technology (MARET) Center building. The new facility offers space for research, education, and certification in the fields of green construction, solar energy, wind energy, and biofuels.

Design

Design

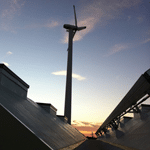

Phase I of the MARET Center included a 10,000-square-foot building powered and maintained by rooftop photovoltaics, a wind turbine, and a comprehensive geothermal system and was completed in 2012. Such features were not only natural, but necessary.

“Firstly, MARET focuses on training,” says executive director Russell Hopper. “Secondly, we are focused on applied research and development, and our third focus is on economic development. From 1992 onward, Crowder has been focused on training and education, and the construction of the MARET Center is the next step for that.”

Interestingly, the new building’s systems are informed by the school’s involvement in the 2002 Solar Decathlon, specifically the various photovoltaic technologies. “The technology we’re using on the building today was developed—if not invented—from the ‘hybrid’ solar panels we built in 2002,” Hopper says. This hybrid technology consisted of a photovoltaic paneling system that pulled the heat from the coils on the backside of the units to provide heat for the building interior via radiant floor panels.

“From the beginning, the MARET Center was designed to be a net-positive energy generator,” Hopper says. “There are 286 solar panels on the roof, and at peak, each panel generates 220 watts, for a total of around 62 kilowatts. We also tied a 65-kilowatt Nordtank wind turbine into the electric system.”

The building features a serrated rooftop engineered to maximize south-facing roof surfaces without increasing shadow or unused interior space. The north wall of the center is made from isolated concrete forms that house the accessible hydronics room, all of which showcase various green building features that can be used to educate students about the implementation of these systems.

The other walls of the center are composed of structural insulated panels, or SIPs. Hopper says that the combination of these various sustainable construction features creates a structurally sound and energy-efficient building with a tight envelope that allows them to use the ERV system primarily for dehumidification, fresh-air exchange, and carbon dioxide removal.

Systems

Heating and cooling of the interior is maintained by a ground-source heat pump and radiant ceiling panels provided by Trane that service both heating and cooling needs. Crowder also worked with Charles D. Jones Co., which provided all of the sensor controls for the building systems.

Inspired by the versatility of the HVAC systems, MARET is also running an on-site experiment split between its two separate geothermal fields—‘hot’ and ‘cold,’ respectively. “After a full-season cycle, we will have dumped all of the heat of the summer into the ‘hot’ field, and all of the cold of the winter into the ‘cold’ field,” Hopper explains. “During the next seasonal cycle, we’ll pull our fluids from these fields and not need to burn any natural gas to supplement climate control.”

Phase II of the MARET Center, which will serve as both an addition and extension of Phase I, is currently underway. “The plans for Phase II are already drawn up,” says Hopper. “All we need to do now is raise money and start on the process again.” Aside from adding office, classroom, and community space, the second phase of the project will also incorporate a central auditorium to serve as a lecture hall, demonstration center, and intellectual incubator for continued research and development.

The MARET Center represents the next step in Crowder’s ongoing leadership in alternative energy research and makes Neosho not only a thoroughfare, but also a strategic, international focal point. “We’ve learned a lot from Phase I of this project,” Hopper says. “We’re really excited to begin Phase II and are already planning ways to make it even better.”