Story at a glance:

- 505 First Avenue is a full-block, high-performance adaptive reuse project in Seattle that has revitalized the building to enhance community engagement, sustainability, and public access.

- The Olson Kundig project features reclaimed timber, salvaged materials, and a warm, tactile palette that bridges the urban and waterfront transitions.

- Through its thoughtful design, 505 First Avenue is more than a green building; it’s a civic gesture that connects the historic Pioneer Square to Seattle’s waterfront.

To design sustainably we need to imagine how a building will live, work, and adapt long after we’re gone. Adaptive reuse is a cornerstone of this idea—working with what exists while preparing it for the environmental and social shifts ahead.

An Opportunity for 505 First Ave

Image courtesy of Olson Kundig

The design of this project was about honoring the intelligence already embedded in a structure and extending its life in a way that feels optimistic. When Seattle’s waterfront reopened we saw an opportunity to reimagine 505 First Avenue through this lens: extending the life of an early-2000s building so it can meet today’s needs while remaining flexible for whatever comes next.

In 2019 Seattle removed the decades-old Alaskan Way Viaduct—an elevated highway that walled off the city from its waterfront—and the relationship between the city and the shoreline changed immediately. Pioneer Square was reconnected to the Puget Sound for the first time in decades. The cleared corridor made space for a new kind of waterfront: an open green promenade designed for people to walk, bike, and enjoy the view. This shift also created the opportunity for us to reimagine the existing building at 505 First Avenue.

How We Did It

505 1st offers an opportunity for tenants to connect with the revitalized waterfront and Pioneer Square neighborhood. Photo by Kyle Johnson, courtesy of Olson Kundig

Pioneer Square has always been a place of transition, occupying space between past and present, land and water. For 505 First the team at Olson Kundig wanted to engage that layered context. Our goal was to modernize an early-2000s commercial structure into a contemporary, people-centered workplace.

With the viaduct gone, the “back” of the building could become a new front door. Now the building opens directly onto the new waterfront promenade and the two-lane bike path along Railroad Avenue South to connect users to both Cityside and Portside bike networks. This simple reorientation fundamentally reshaped how people experience the building and how the building participates in its city.

- A double-height greenhouse and a warm, tactile material palette of reclaimed wood, natural steel, and concrete marks the progression between urban and interior environments. Photo by Kyle Johnson, courtesy of Olson Kundig

- The interplay of old and new, industrial and organic, ties the building back to Seattle’s culture of craftsmanship and stewardship. Photo by Kyle Johnson, courtesy of Olson Kundig

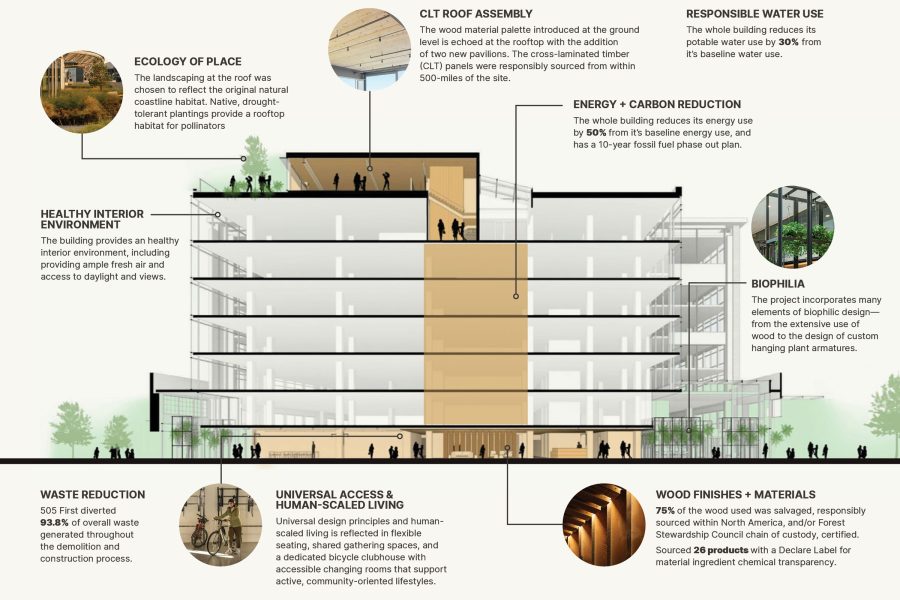

At every level our design strategy reduced waste, extended material life, and lowered the embodied carbon wherever we could. We sourced 23% of materials locally and used 75% salvaged, responsibly sourced, or FSC-certified wood, including CLT panels manufactured within 500 miles, and reclaimed timbers from the original structure. Working with these materials allowed us to retain the building’s character while giving it a renewed sense of craft and clarity. Across the project 26 materials carry Declare Labels to ensure chemical transparency and support the project’s pursuit of International Living Future Institute’s Core for Interiors certification.

Resource management guided both construction and day-to-day operations. We diverted more than 93% of demolition and construction waste from landfills. The building now uses 50% less energy thanks to an electric heat-pump water system, smart lighting controls, and a 10-year transition plan to phase out fossil fuels entirely. Water-saving strategies cut potable water use by 30%, and upgraded systems improve indoor air quality and overall comfort.

- The privately owned but publicly accessible lobby creates an indoor urban street that welcomes commuters, tenants, and visitors. Photo by Kyle Johnson, courtesy of Olson Kundig

- The landscape design emphasizes succession planting, allowing species to evolve and self-seed over time without irrigation. Photo by Kyle Johnson, courtesy of Olson Kundig

Inside we reimagined the lobby as the social threshold of the building. What had been a closed-off, underused space is now a well-lit passage linking Railroad and First avenues. It operates like an indoor urban street where people can gather or simply move through. The rhythm of FSC-certified and reclaimed timber screens add warmth and an approachable scale, while flexible seating and generous circulation make the space accessible to all. We wanted this space to quietly support daily rituals in an intuitive and welcoming way. It creates small daily moments of connection that shape the experience of the building.

Sustainability also informs how people move to and through 505 First. The Bicycle Clubhouse embodies this idea with its position along the new waterfront trail and supports cyclists with secure storage, repair and wash stations, lounge areas, and direct street access. We felt biking had to be part of the building’s identity. We hope by prioritizing cycling and accessible bike parking it will help reduce car dependency and encourage a more active, low-carbon way of commuting.

Wellness shaped the broader interior environment as well. More than 80% of office spaces receive natural daylight, and sensors adjust lighting levels throughout the day. Access to fresh air, views, and pockets of vegetation—including the hanging basket greenhouses at both entries of the lobby—reinforce the connection between work and well-being. These elements create a workplace where comfort, productivity, and environmental responsibility reinforce one another. These choices remind us that sustainability is as much about human experience as it is about measurable performance.

The original roof was a flat, hardscaped space with mechanical equipment. Olson Kundig goal wanted to create a living landscape, so they reintroduced native, drought-tolerant plantings inspired by the historic Puget wetland that once occupied the shoreline. Photo by Kyle Johnson, courtesy of Olson Kundig

Above the city the rooftop transformation adds another layer of ecological restoration. The original roof was a flat, hardscaped space with mechanical equipment. Our goal was to create a rooftop that functions as a living landscape, so we reintroduced native, drought-tolerant plantings inspired by the historic Puget wetland that once occupied the shoreline. The landscape design emphasizes succession planting, allowing species to evolve and self-seed over time without irrigation.

Beehives also occupy part of the rooftop to support pollinators and reconnect the building to regional biodiversity. Tenants have a choice between sheltered spaces with expansive views inside two CLT wood-and-glass pavilions or outdoor areas shaped by planting beds that reflect the changing seasons. The roof amenity has become a quiet counterpoint to the energy of the street below and allows tenants to work, hold events, or connect with nature while overlooking the Puget Sound and Olympic Mountains.

Flexible seating and generous circulation make the space accessible to all. Photo by Kyle Johnson, courtesy of Olson Kundig

Our intent was to engage and even extend the history of the site by repositioning the building to feel both timeless and forward-looking. Sustainability at 505 First Avenue is a dialogue between the existing structure and the new layers we’ve added.

The historic brick facade now works alongside kinetic elements, timber structures, and living vegetation. This interplay of old and new, industrial and organic, ties the building back to Seattle’s culture of craftsmanship and stewardship. It’s a reminder that while strong performance metrics are important, true sustainability is about anticipating how needs might change and then designing spaces capable of evolving and connecting with their communities for decades to come.

Drawing courtesy of Olson Kundig