Story at a glance:

- Basalt architects share the plans for their new housing development as apart of the city’s densification plan.

- Green Building Council officials and city officials discuss what Reykjavik must accomplish on individual and local levels.

- The Municipal Plan is a guiding force for green building in Reykjavik.

A country smaller than Ohio and less populous than Cleveland sits atop the world—both geographically and as one of the globe’s leading sustainable countries. Iceland’s capital, Reykjavik, is situated at the southwestern corner of the island country in the North Atlantic sea. With a population of less than 125,000, it’s an increasingly international tourist destination thanks to its many volcanoes, geysers, and hot springs.

Like its neighbors in Norway, Iceland is also a leading example of how to design for the fight against climate change, especially when you have a coastline that’s at risk. Fjola Kristjánsdóttir, CEO of the Green Building Council Iceland, says that while in recent years Iceland has done a lot of good in terms of producing sustainable energy, it’s time to look beyond that. She wants the country to focus more on sustainable transportation and green buildings, too.

Two years ago Green Building Council Iceland lobbied the government to include the building sector in its Climate Action Plan, and Kristjánsdóttir says the council is currently focused on green financing—working to encourage banks to invest in the building sector. Kristjánsdóttir says Reykjavik is also working hard to create a more economic, social, and environmentally sustainable city and achieve carbon neutrality by 2040. It’s all part of the 2010-2030 Reykjavik Municipal Plan.

Photo by Ragnar Th. Sigurdsson

How We Got Here

But first, how is Reykjavik one of the most sustainable cities in the first place? The city ranked among the top cities in the world for its environment in the 2019 Global Destination Sustainability Index, a global sustainability benchmarking and improvement program for business tourism and events. More than 99% of electricity production and almost 80% of total energy production in Iceland comes from hydropower and geothermal power, according to the Reykjavik Convention Bureau.

Stand almost anywhere in the country and you can see its many mountains and glaciers. But what you can’t see, at least not really, is the geothermal energy churning below the rugged fjord-lined landscape. One way to get close to that energy, and many tourists do, is with a quick trip to the Blue Lagoon—a 20-minute drive from the airport.

The Blue Lagoon is an otherworldly spa heated by a geothermal energy plant, and it’s many tourists’ first stop in Iceland. Basalt Architects, a leader in green building in Iceland, completed The Retreat at Blue Lagoon in 2018. Photo by Ragnar Th. Sigurdsson

The Blue Lagoon is a geothermal spa heated by the runoff of a neighboring geothermal energy plant, where people come from across the world to bathe under Mount Thorbjörn. Geothermal energy is produced in abundance due to Iceland’s unique geography—sitting on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge between the North American and Eurasian tectonic plates. There are at least 200 volcanoes in Iceland, according to the National Energy Authority of Iceland. Geothermal energy now accounts for 25% of all energy in the country and is often used in tandem with hydroelectric energy as an alternative to fossil fuels.

Building for the Future

Well-known Icelandic firm Basalt completed The Retreat at Blue Lagoon in 2018, designing the hotel and spa to fit within the existing natural landscape. Basalt has been focused on green building since its inception in 2009 and has also been part of Green Building Council Iceland and Nordic Built for more than 10 years. Most recently they’ve been active in the city of Reykjavik’s green building plans.

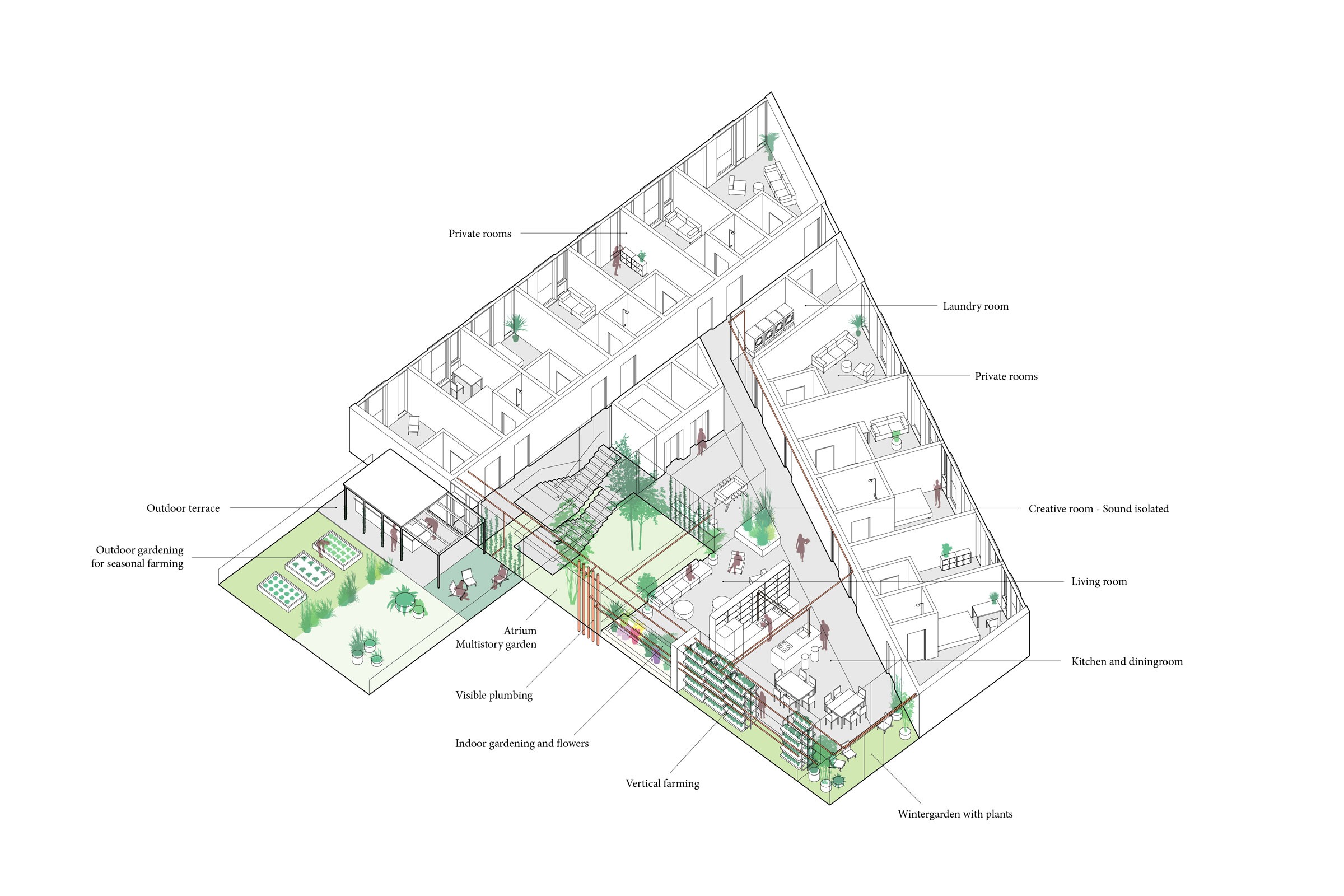

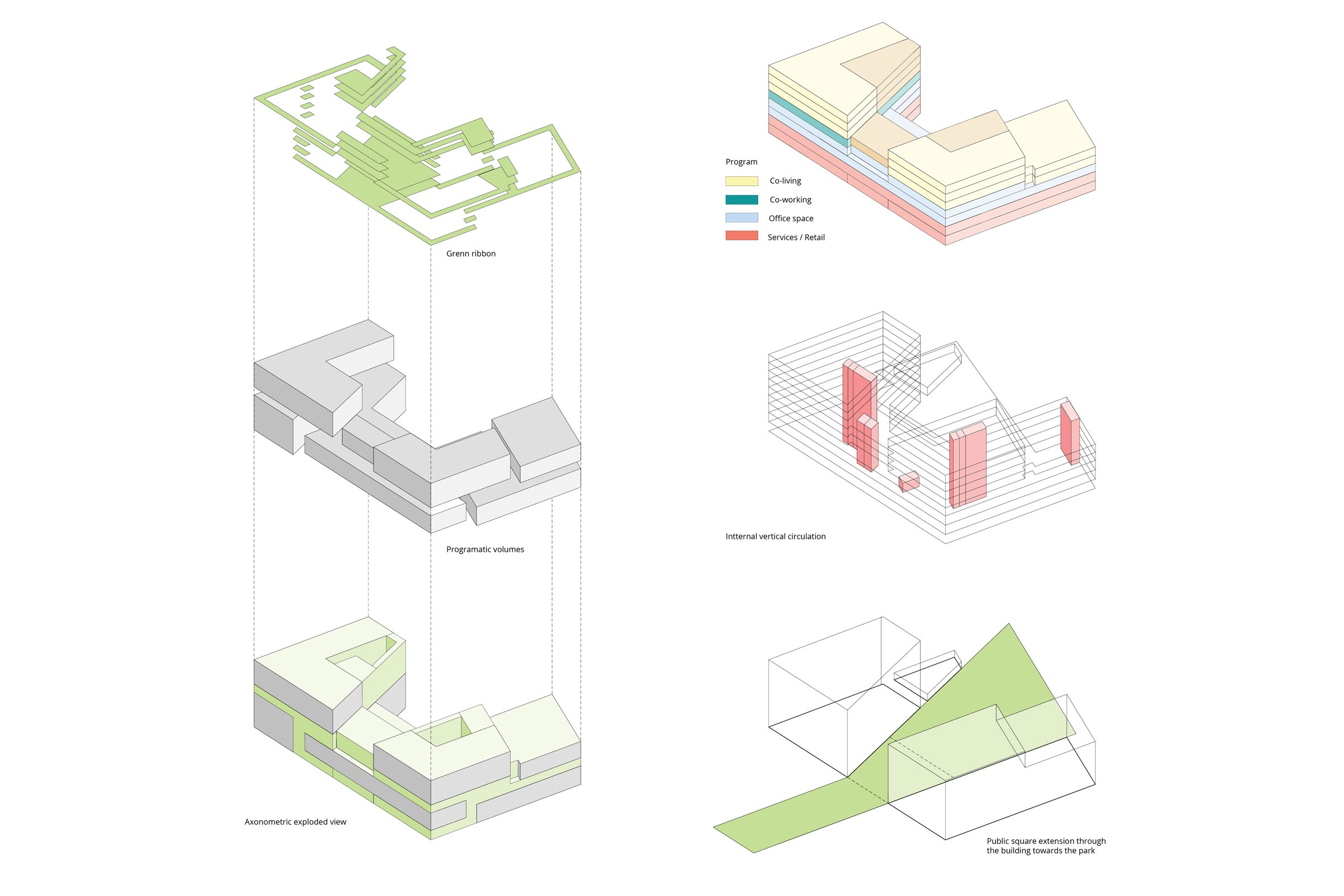

Since 2017 Basalt has been at work on a project called FABRIC, an eight-story building complex that’s deeply rooted in the city’s shift toward co-living and co-working. The design was recognized as the top project in the 2019 C40 Reinventing Cities competition—a call for urban projects to drive carbon-neutral and resilient urban regeneration in cities across the globe. On the outskirts of downtown and a short walk to the water, the 15,000-square-meter FABRIC will soon be home to both shared and private co-living spaces, co-working offices, urban farming, retail, a bike shed, and more. The project is also on the direct route of the new city bus line.

The design for FABRIC was recognized as the top project in the 2019 C40 Reinventing Cities competition—a call for urban projects to drive carbon-neutral and resilient urban regeneration in cities across the globe. Courtesy of Basalt

Like many successful projects in Iceland, geothermal energy is at the core of FABRIC’s sustainable success. But the design takes that advantage—access to geothermal—and pushes the envelope even further. “The goal is to make this project a beacon, a new way of building,” says Hrólfur Karl Cela, partner at Basalt Architects, adding that the design is built around the geothermal resources onsite. “We want all the piping on the building to be visible and easily readable so users start to understand the processes and resources behind our infrastructure. If you talk to small children about where water comes from, they say the tap. Well, no, not really.”

FABRIC is uniquely situated atop a former geothermal drilling zone and, because of recent advances in drilling technology, the zone no longer needs to be preserved for direct drilling. Geothermal energy can still be produced from this plot while it’s developed aboveground, Cela says.

FABRIC is an eight-story building complex that’s deeply rooted in Reykjavik’s shift toward co-living and co-working. Courtesy of Basalt

But geothermal energy is just one aspect of this building’s sustainable development; the design team also chose to build with cross-laminated timber, known for its design flexibility and low environmental impact. And design elements like the “Green Ribbon,” a long green space that extends between floors and rooms, functions as both a channel for geothermal ductwork as well as a green space for farming and gardening. “It’s a really active hub—not only the building itself but also how it channels the city through it,” says Marcos Zotes, partner at Basalt Architects, of FABRIC’s connected living, working, gardening, and retail spaces. “It should promote a healthier way of living. The aim is to have services that reflect this—medical offices, psychology offices, et cetera.”

Basalt Architects designed FABRIC, an ongoing project in Reykjavik that uses low- carbon construction materials. FABRIC incentivizes alternative and communal ways of living and working—mixing housing, office space, public space, service, and retail. Courtesy of Basalt

Redefining Affordable Housing

The city of Reykjavik says a big part of making sure the city is both healthy and happy goes back to making sure everyone has a place to live. “Social sustainability will not be easily reached, but Reykjavik’s policies of providing affordable housing in every city district, diverse housing solutions for all social groups in all neighborhoods, and continued provision of essential public services for everybody are ways to tackle that issue,” says Ólöf Örvarsdóttir, head of Reykjavik’s environmental planning department. The Municipal Plan of 2014 demanded that at least 25% of city housing units built be affordable. Reykjavik has exceeded that goal, as about 35% of all development has been allocated to affordable housing since 2015.

“When talking about affordable housing we shouldn’t think so much about cutting costs because it will be worth it if people will get a better life in those houses,” Kristjánsdóttir says. “We should look to Denmark, Germany, and Norway when we think about affordable houses.” In Denmark, for example, “eco villages” offer an alternative way of living as a community while working to save the planet. Denmark leads the world with the highest number of eco villages per capita as of 2018, according to Eco Villages of Europe’s website.

Using What You Have

Reykjavik’s Municipal Plan also calls for 90% of residential units to be made from existing structures. The idea is that the most sustainable option is to work with what’s already there. “We have to think of materials as a very valuable thing. Sometimes people say, ‘Oh, we haven’t done anything to maintain that building so tear it down,’” Kristjánsdóttir says, but that simply shouldn’t be the way. She says the city is also calling for designers to create buildings that are more flexible. For example, while there may be a surge in elementary-age children and a need for a school right now, in 20 years there may be a larger population of elderly folks and a need for nursing homes.

The Municipal Plan also aims to curb building beyond city limits, insisting that the closer together that infrastructure is built the more green spaces can be preserved. “We have quite good access to green areas and the sea, though we have a very scattered city, and we need to change that,” Kristjánsdóttir says.

Örvarsdóttir agrees, saying the plan aims to “make the city structure more compact, with more dense and mixed neighborhoods, which supports sustainable travel modes. Priority is given to densification close to public transportation and employment centers.”

Algaennovation, an international tech startup developing new technologies for producing micro-algae, gets all of its water and electricity from a geothermal power plant in Iceland. Photo by Ragnar Th. Sigurdsson

Getting Where You Need to Be

Transportation is also a top concern in the city’s municipal plan. Moving people into taller, denser structures aims to reduce personal car usage, as people will be closer to work, shopping, and dining. The city hopes to reduce carbon emissions by reducing car trips, and a new transportation system called the Borgarlína, or City Line, is underway, Örvarsdóttir says. “It’s very important that the city authorities guide the way with policy-making, provision, and investment in the right services and infrastructure and serve as a role model for private firms and the inhabitants of the city—because in the end, it’s the daily activity and consumption that counts in dealing with the climate change.” The city is also encouraging more walking and biking, and Örvarsdóttir says bike lanes have increased by 67% in the last few years and the number of bikers nearly doubled.

The city wants to celebrate not just the designers and architects who are helping to make Reykjavik even greener, but also the city’s residents themselves. Kristjánsdóttir says more people were walking and biking during the peak of COVID-19, and she hopes residents will keep that momentum going. “We need to put our people who are using environmental transportation on the red carpet, not somewhere in the background.”