Story at a glance:

- The adaptive reuse of Turtle Bay Towers was unprecedented when the project was completed in the 1970s.

- The New York City project helped to introduce the idea of artists’ live-work lofts with abundant space and light.

- Some industry experts say affordable housing could be the answer to filling vacant office buildings all over the US.

It was the 1970s, and a young group of architects (now renowned as RKTB Architects) was tasked with a major challenge—save a 26-story, 1929 loft building that was badly damaged in a gas explosion. Called Turtle Bay Towers, the project is both one of New York City’s and the firm’s earliest large-scale adaptive reuse successes.

- Photo courtesy of RKTB Architects

- Photo courtesy of RKTB Architects

As many towering office buildings sit vacant all over the US today, RKTB Architects says this transformation could be an example to other architects as well as developers and city officials. These empty buildings could also fill a major need for affordable housing.

“Adaptive reuse is smart and sustainable thinking, and office buildings represent an opportunity to address a major housing gap today,” says Carmi Bee, principal in charge of design with RKTB Architects. “Post-COVID it’s not at all certain that these commercial spaces will fill up with new leaseholders, especially as much of the existing stock lacks the infrastructure needed to support the activities and workflow of the high-tech companies most likely to sign big new leases.”

Bee says the Turtle Bay Towers project, completed in 1978, set a precedent. It could also light the way for more major adaptive reuse projects.

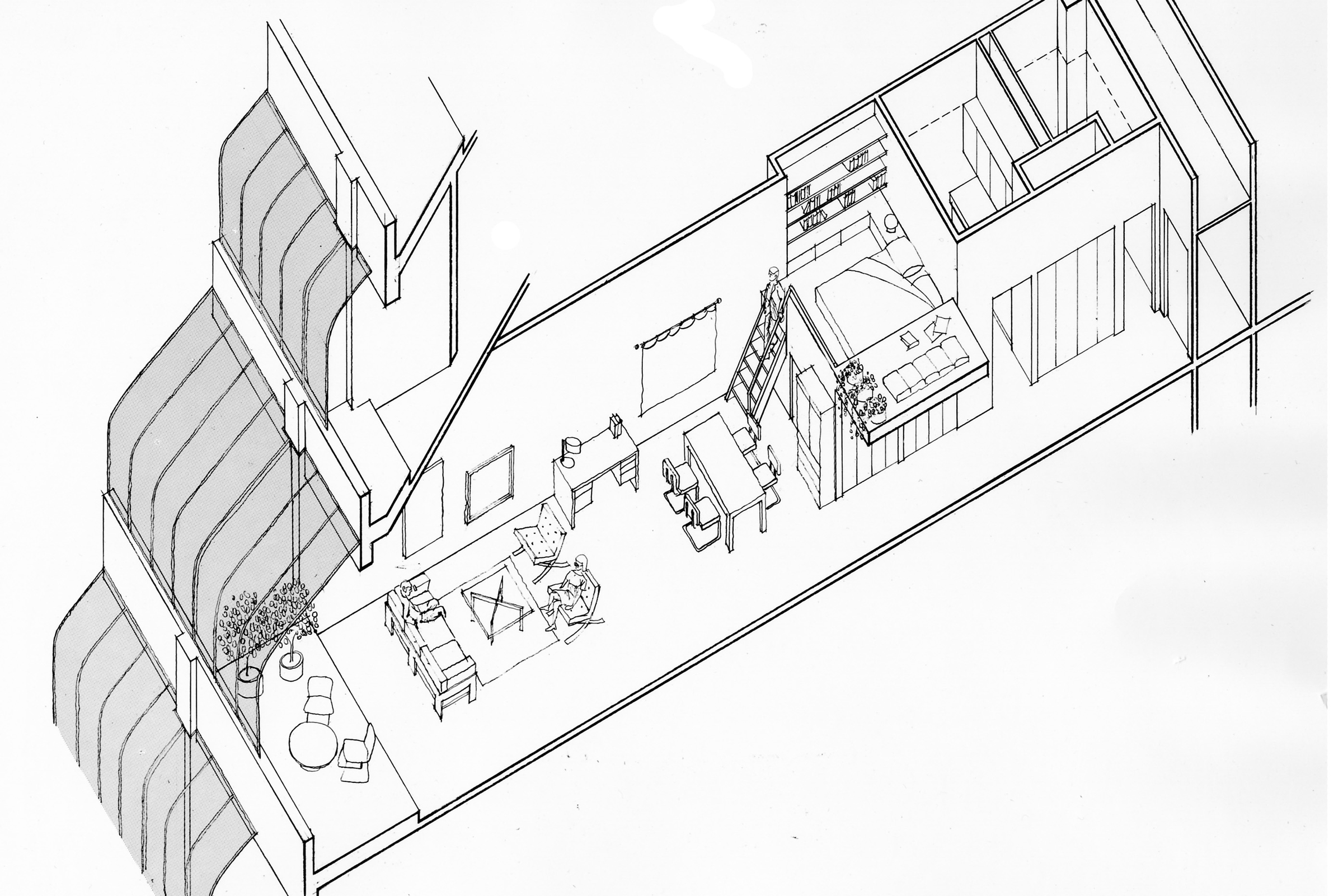

Turtle Bay Towers. Drawing courtesy of RKTB Architects

“The entire project was a challenge, since nothing like it had been attempted,” Bee says. “The project was one of the first for developer Rockrose Residential, now a major name in New York luxury rentals. This was one of their first. It took some courage for them to create Turtle Bay Towers and invest in an untested idea, although the location certainly helped (Midtown East near the United Nations).”

Turtle Bay Towers was being used for offices and light manufacturing when an explosion funneled up the elevator shafts in 1974, blowing out a 50-foot-wide section of the brick facade from street level to the top story.

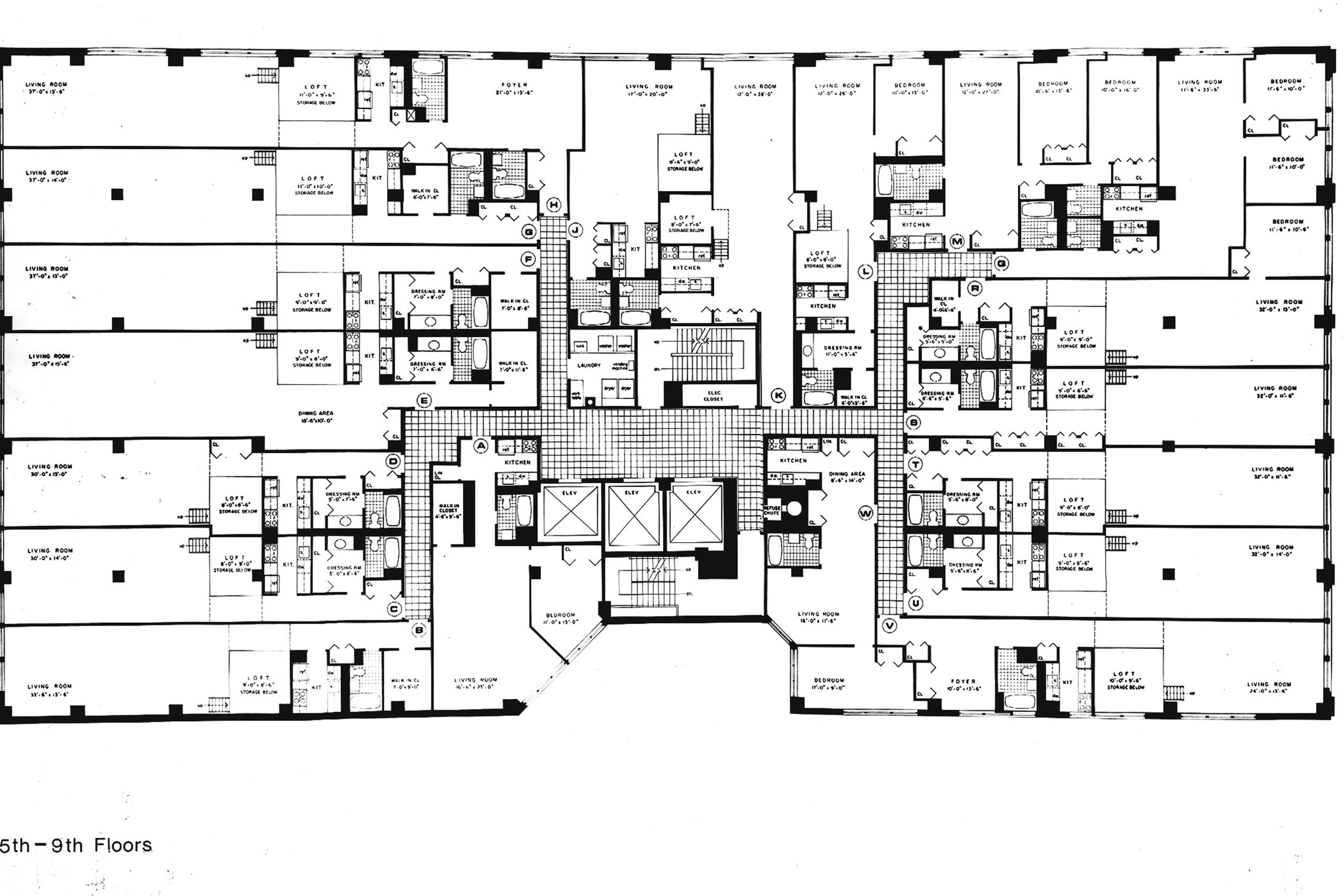

“Few expected anyone to find a way to salvage the building for reuse, and even fewer thought it had any potential as housing. Because it was a through-block building, no one could imagine any way to introduce enough light, because there were windows only on the sides facing 46th and 47th Streets,” Bee says.

Inside Turtle Bay Towers. Photo courtesy of RKTB Architects

“Our attempt to adapt the building as multifamily housing coincided with the rise in popularity of live-work lofts and residential styles previously favored by artists. By reclaiming some of the height of each floor we were able to introduce sleeping lofts, which really made the project work. It was very chic suddenly to live in the Bohemian style in a huge soaring space, so the project’s timing was ideal.”

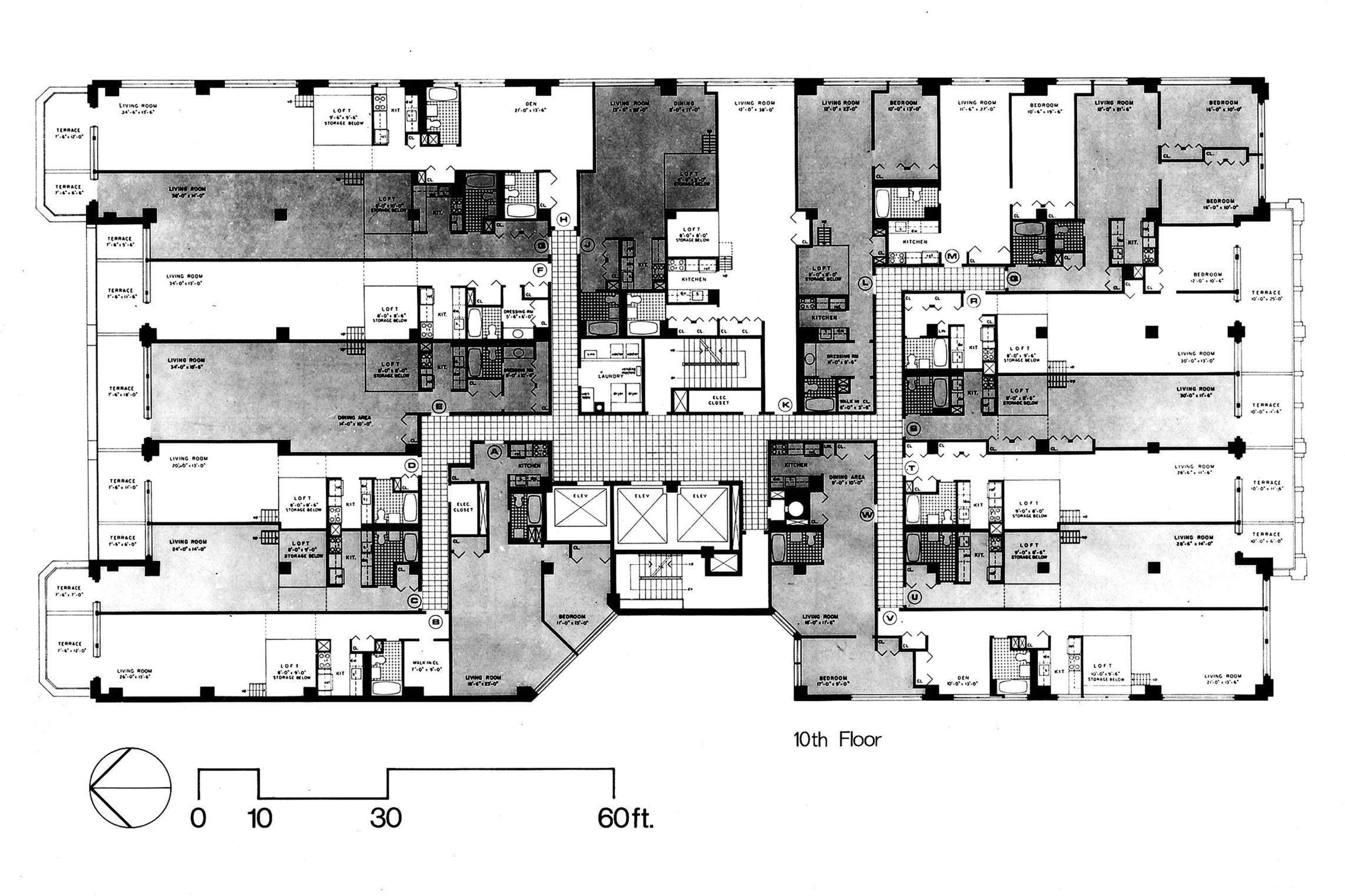

RKTB was able to redevelop the square footage of the elevator shaft and transfer it to the setbacks on the higher floors of the wedding cake-style building, which they enclosed in greenhouse-style windows. “The result was a breakthrough in housing typology. No one had seen anything like it except in artist housing,” Bee says.

Photo courtesy of RKTB Architects

By converting the elevators to passenger use and cutting away the demolished shafts, the design provided a street-level courtyard that opened up a full 200-foot height of the west wall of apartments to natural light. This change decreased the building’s total volume, and zoning regulations permitted this lost space to be regained in the form of those greenhouse windows.

“For us it was exciting to have the chance to be inventive and creative, solving multiple problems with a design solution that created fabulous homes. We were humbled to receive an AIA Honor Award, bestowed in recognition of the project setting a new precedent and offering a new way of thinking about housing and development,” Bee says.

Inside the old Turtle Bay Towers in Manhattan. Photo courtesy of RKTB Architects

RKTB has thrown its support behind creating more affordable housing solutions and saving historic buildings, inspired in part by their own design of Turtle Bay Towers. Bee says putting the right policies and incentives in place is critical. A mix of tax breaks and zoning and building code exceptions could make converting commercial office properties into affordable housing a faster and more widely adopted solution.

Turtle Bay Towers. Floorplan courtesy of RKTB Architects

Turtle Bay Towers. Floorplan courtesy of RKTB Architects

But these efforts are not without challenges, and most of those challenges reflect the basic requirements for habitable residential units, which office structures often lack. For example, healthy living spaces have robust ratios of window area to floor area.

Over the years RKTB has converted a number of commercial buildings into market-rate and even luxury residences, cutting straight through the floor plate on every floor to create a central atrium, bringing abundant natural light and air deep into the buildings. Bee points to Turtle Bay Towers in Manhattan’s Midtown East as one of the firm’s earliest such works, as well as Franklin Trust Tower in Brooklyn Heights and a landmark warehouse in Brooklyn’s Fulton Ferry District.

Regulations governing affordable housing present other challenges. For example, New York City’s Department of Housing Preservation and Development recently published a new set of design guidelines for affordable housing, which Bee thinks could lead to cramped conditions in some locations.

Peter Bafitis, Bee’s partner and a co-chair of the AIA New York Chapter’s Housing Committee, agrees. “People need a comfortable, healthy place to live. It’s not enough to deliver something affordable,” he says.