Since the mid-2000s, shotcrete usage in underground construction has soared because contractors can install it more quickly and efficiently than traditional cast-in-place concrete systems. Project teams have supported adoption of the technology based on what has been described as a meaningful schedule acceleration of the time typically required to complete a foundation. For large-scale projects, that can translate into millions of dollars through accelerated occupancy and timely project completion. With this surge in shotcrete use comes advancements in waterproofing systems designed specifically for the material.

Cast-In-Place Concrete vs. Shotcrete

Below-grade construction with cast-in-place concrete requires installing forms in the excavation, pouring concrete, waiting for it to cure, and, finally, removing all the forms. Shotcrete application is typically faster because it can be done quickly by qualified nozzle operators without the need for concrete formwork.

However, shotcrete does come with its own set of risks. For example, shotcrete use can lead to voids in concrete walls and behind rebar. These problems can allow water to migrate around and into a structure should the waterproofing system fail. Water migration can derail timely project completion at great cost, while exposing the structure to leaks and flooding over its useful life.

The force of shotcrete spray can also damage waterproofing membranes, as can the impact of adjacent building construction and flaws introduced by rebar, electrical, or plumbing contractors.

GCP Applied Technologies’ PREPRUFE waterproofing system. Photo courtesy of GCP Applied Technologies

Searching for a High-Performance Waterproofing System

When first working with shotcrete, contractors tried adapting preapplied waterproofing solutions traditionally used with cast-in-place applications to shotcrete projects. After shotcrete was placed on the waterproofing membrane, contractors were forced to seal leaks by drilling holes through the shotcrete wall in trouble spots and injecting grout. As contractors could not see or track the pattern or extent of the vulnerability, the only method of filling the void or defect with grout was time-consuming trial and error. This blindside approach produced only limited success or outright failure.

One solution to these deficiencies is use of an effective shotcrete waterproofing system, which includes a membrane, grout-injection tubes, and grout. A tough composite membrane can stand up to the force and application of shotcrete, while a polymer-mesh-reinforced cavity sits between a layer of plastic film and a nonwoven, semipermeable geotextile.

In step one of the application process, the contractor attaches the membrane to the soil retention wall—typically a combination of piles and lagging. Before applying the shotcrete, the contractor fastens a spaced matrix of injection tubes onto the geotextile of the membrane. In step two, the grout is injected through the tubes after the shotcrete wall has cured. This can be one to two months after the construction of the wall and is a process that can be completed as construction moves beyond the foundation, allowing for schedule acceleration.

During injection, the reactive grout fills the cavity created by the membrane and permeates through the geotextile. As a result, it forms a monolithic curtain wall of grout, proactively sealing voids in the wall itself and creating a high-performance waterproofing system bonded to the shotcrete.

Combining preapplied membrane technology with injected leak-sealing materials results in a fully integrated waterproofing system. This two-step method stops leaks before they happen, ensuring construction stays on schedule, liabilities are minimized, and the waterproofing solution shields the structure from water infiltration throughout the design life of the project. With this type of technology at their disposal, engineers and general contractors are increasingly turning to shotcrete to accelerate their high-profile, high-risk projects.

Case Study: Rebuilding a Major Highway System

The Alaskan Way Viaduct in Seattle is a North-to-South traffic corridor that carries tens of thousands of commuters through the city daily. Built as a bridge in 1953, the viaduct was damaged in 2001 by an earthquake. In 2013, construction crews began replacing it with a 3-kilometer (2-mile) long tunnel beneath the city at a projected cost of $4.5 billion.

The tunnel’s north and south portals span about 609 meters (2000 feet) and start at grade before plunging about 24 m (80 feet) deep. Adding to the complexity, multiple highway lanes merge into different levels of the tunnel. The job site also sits at sea level in a city known for its extremely wet climate.

Waterproofing of the viaduct began in June 2013. The waterproofing contractors installed about 32,516 m2 (350,000 square feet) of shotcrete waterproofing, or 55,742 m2 (600,000 square feet) of waterproofing membrane in total. In addition to protecting the viaduct, an additional 13,935 m2 (150,000 square feet) of membrane was utilized on the portals and the viaduct’s operations buildings. Multiple systems were employed to accommodate the use of both shotcrete and cast-in-place concrete.

Despite soaking rains and leaky ground, the team completed the project in 2016, on time and without incident. Field engineers were onsite throughout the waterproofing process, ensuring proper installation of the waterproofing systems, training contractors, and troubleshooting any issues.

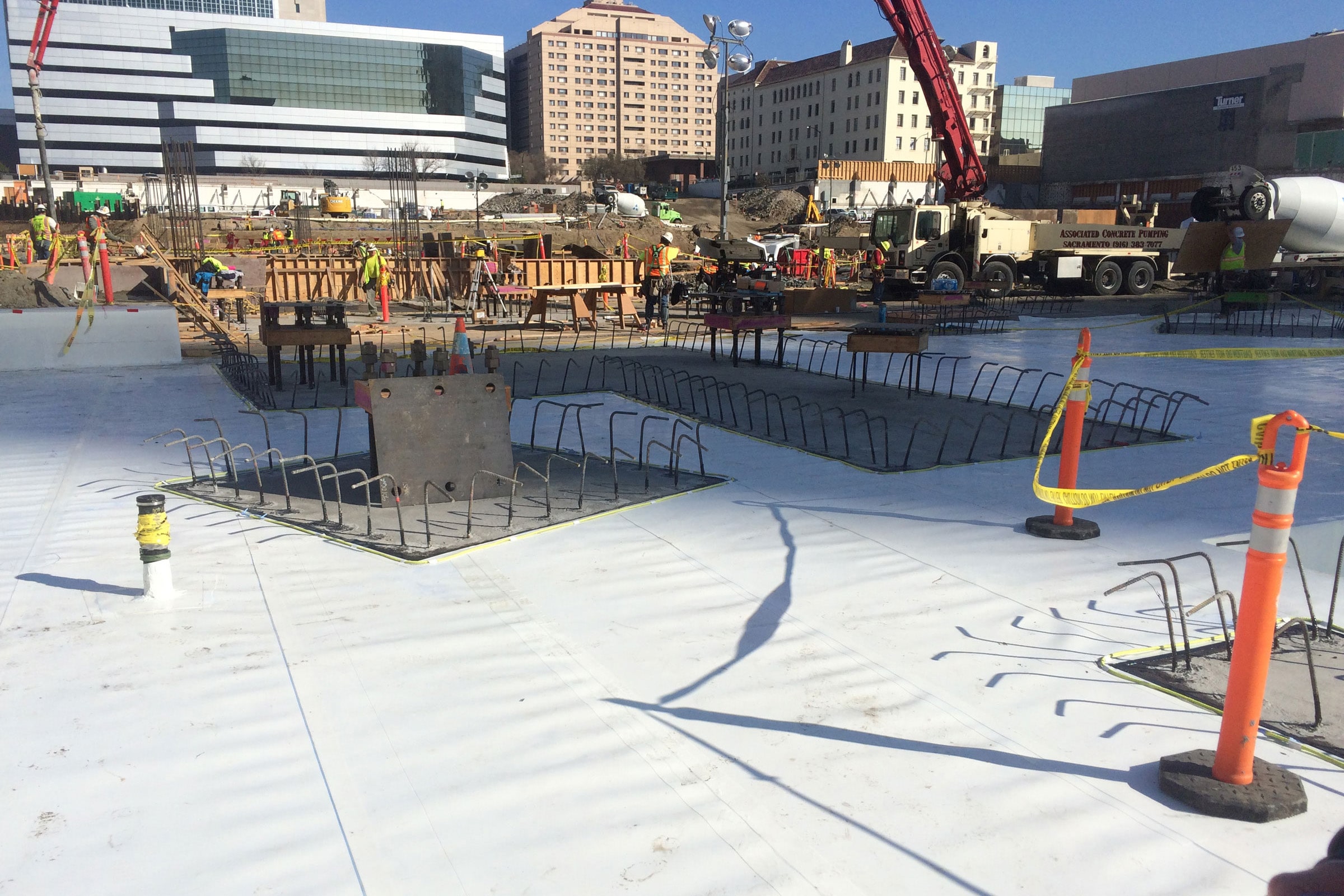

The Golden 1 Center in Sacramento used GCP Applied Technologies’ PREPRUFE waterproofing system. Photo courtesy of GCP Applied Technologies

Case Study: Tackling a Stadium-Sized Challenge

In 2014, general contractor Turner Construction was tasked with building the Golden 1 Center, now home to the NBA’s Sacramento Kings. The owners gave Turner less than two years to complete the 17,500-seat, $507 million arena.

Turner chose F.D. Thomas as the waterproofing contractor to take on the challenges of a stadium that sits below the water table and is adjacent to two major rivers. For its waterproofing system, the contractor selected an integrated waterproofing membrane.

Rainstorms dumped 0.9 meters (3 feet) of water on the excavation before F.D. Thomas began installation. Despite the flooding, the contractor completed the job in just 45 days. Stuart Hunter, vice-president of F.D. Thomas’s waterproofing division credits his colleagues, the teamwork of Turner, and the concrete, rebar, and plumbing subcontractors—as well as the waterproofing system—for executing the task under pressure and finishing 15 days early.

Since opening in September 2016, Golden 1 Center has operated without interruption due to leaks or flooding.

Shotcrete in Practice

Advancements in waterproofing have enabled the rapid growth of shotcrete usage in traditional structural applications. With this type of technology available, contractors, designers, installers, and engineers will continue to expand the use of shotcrete, reaping the associated schedule benefits.