Story at a glance:

- NYSID’s Master of Professional Studies in Sustainable Interior Environments emphasizes that energy efficiency, health, and eco materials don’t have to be at odds with good design.

- There is a growing interest and need for intergenerational housing that enables more belongingness and allows the older, retired generation to assist in caring for the youngest family members.

- Designers need to more fully incorporate and integrate equity, and NYSID revamped its project briefs in both the fall residential studio and the spring contract studio to do so.

Environmentalism has often been defined by the triple bottom line. In its first incarnation it was the three Ps of people, planet, and profit. In more recent years it’s been superseded by the (arguably more accurate) three Es of economy, ecology, and equity. This variation, by replacing the business world origins of the triple bottom line, was also better suited to the goals of sustainable design.

Economy, Ecology, and Equity in Sustainable Design

Mountain Center Youth Residency Retreat by Sarah Espinosa and Madelyn Cichy. Image courtesy of NYSID

Ecology is the one most of us are most familiar with. It’s where sustainability—back before it was called that—and sustainable design have focused: how we directly address ecological issues such as climate change, resource depletion, water pollution and scarcity, biodiversity, and so forth.

Economy, a far better term than the confusing and capitalistic “profit,” addresses the micro- and macroeconomic costs and a related concept I’ve termed “Eco Optimism”—the under-emphasized point that the steps needed to mitigate environmental ills will, contrary to what many people object to, often improve more than just the environment.

Of those three Es we’re only now really beginning to come to terms with equity, or what had been known as “people” in the three Ps. In its most fundamental definition equity looks at individual and community health and environmental justice and acknowledges that much of the world has benefitted less from economic development while bearing a disproportionate environmental burden.

How NYSID Embraces Equity

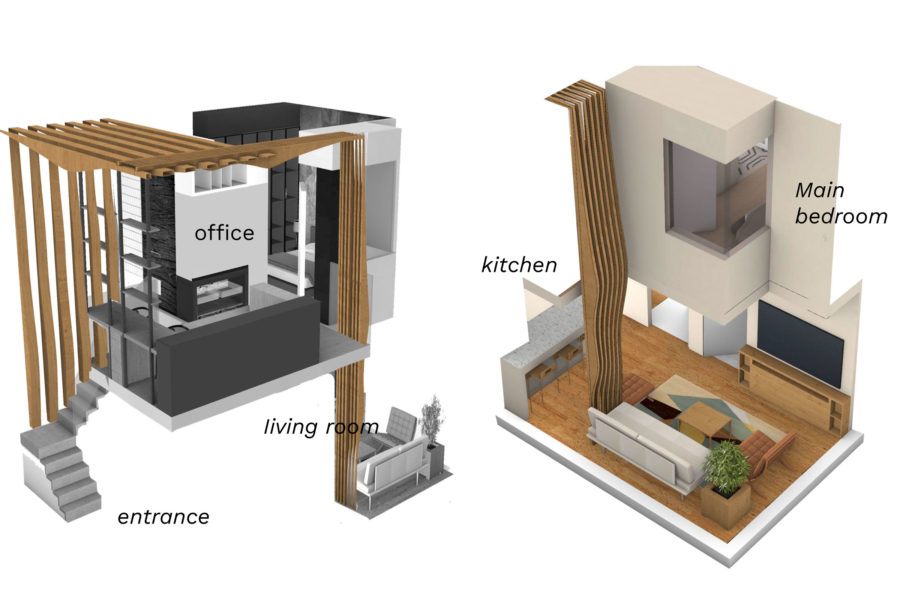

Site plan and Accessory Dwelling Unit floor plan of Seattle townhouse project by Linda Diaz. Image courtesy of NYSID

From the point of view of a sustainable interior environments program, what that means is going beyond the essentials of ecodesign. Yes, sustainable interior design has come a long way. It’s matured to a pretty good understanding of energy efficiency, health, and eco materials (especially now that the carbon footprint significance of interior design materials is becoming better understood) and has proved we can do this without sacrificing design.

Indeed, that’s one of the explicit goals of sustainable design at the New York School of Interior Design (NYSID), and more specifically in our Master of Professional Studies in Sustainable Interior Environments. In the MPSS studios we don’t separate the aesthetics of design (let’s call that the Fourth E, for the British esthetics) from ecology and economy.

With ecology, economy, and aesthetics more or less in hand, what about the missing E of equity? Two years ago, in an acknowledgement that we need to more fully incorporate and integrate equity, we revamped the project briefs in both the fall residential studio and the spring contract studio.

Here are five examples of sustainable design projects.

1. A Townhouse in Seattle

One of the fall briefs in NYSID’s MPSS studios had involved renovating a high-end townhouse in Seattle. We cut down the McMansion-esque size of the house and, in its place, added a Detached Accessory Dwelling Unit for the family’s grandparents.

An aspect of broadening our project briefs has been to include diverse clients and non-traditional families. This project acknowledges the growing interest and need for intergenerational housing, which enables more belongingness, allows the older, retired generation to assist in caring for the youngest family members while the parents worked and, simultaneously, addresses the housing shortage.

2. A Duplex Townhouse Apartment in Manhattan

Lower level and section of Manhattan intergenerational duplex apartment, Johanna Sy and Samantha Berlanga. Image courtesy of NYSID

As with the Seattle brief, we modified this assignment to make it intergenerational. It became a residence for an elderly woman living alone and a NYSID student who would offer company and assistance. The students had to work on how to give each of the occupants personal space while providing the degree of interaction the owner desired.

3. Tiny Homes and 4. Micro-Apartments

Concept for Brooklyn cohousing micro-apartment by Amaris Woodson, Tugce Buran and Jiayi Xu. Image courtesy of NYSID

We then added two briefs for cohousing/intentional communities composed of tiny homes (for the rural one) and micro-apartments (for the urban one) in conjunction with communal shared facilities to augment the small individual residences.

Intentional communities look to balance needs for individual or family space with the benefits, both environmental and community, of shared facilities. For each of those projects the students were assigned the communal space and one of the residences.

A tiny home or micro-apartment might have, for instance, a small, basic kitchen and eating area—the type that many use daily—while having access in the communal facilities to a larger and better-outfitted kitchen and a dining area for a group gathering.

Rather than having that expensive Peloton idly taking up valuable space at home (how many of us have, with the best of intentions, purchased one only to have it become an annoying reminder that we should, but aren’t exercising?), members have a gym upstairs or across the yard. No space for a workbench? You can have a well-stocked workshop or a tool library.

So how do you design to interpret this new typology best and most environmentally? The students with those two briefs got to investigate that.

5. A Southwestern Home Turned Retreat Center

A fifth brief took the footprint of a previously assigned southwestern home and, instead of designing it for a presumably wealthy family, made it a residency retreat center for a youth program providing vocational and leadership training in land management.

Exploring the Future of Sustainable Design

Common space of Brooklyn cohousing project by Amaris Woodson, Tugce Buran, and Jiayi Xu. Image courtesy of NYSID

In each case, though the assigned clients were different from the previous focus on, one might say, two of the three Es, adding the Equity leg by no means meant sacrificing that implicit Aesthetics fourth leg. Just because the clients (expecting maybe the Manhattan brief) were not in the one percent, did not mean we no longer emphasized design.

This expanded approach has also emerged from a course we instituted two years ago: Frontiers of Sustainable Interior Environments. The course is offered in the final semester where we say to our soon-to-graduate students: Now that you know what sustainable design is and now that the interior design field is beginning to truly embrace sustainability, let’s talk about what it needs to be, and what the next goals and frontiers are.

We do this through a combination of student research and guests who are working in those frontiers. Some of it is about the next steps for obvious topics such as certifications and developments in new materials, but much of it is also about how we break sustainable interior design out of its reputation for being for the well off.

We start by understanding that healthy environments should, of course, be for everyone. Why should the residents of a low-income apartment building be exposed to toxic materials, while more affluent clients are not? Why should fast food or less tony restaurants not receive the same attention to environmental health?

Admittedly, these project briefs are US-specific. Ideally equity should be addressed internationally with an emphasis on the countries and groups, as mentioned above, that have been most affected by environmental issues. There’s a larger discussion to be had about the difficulty of designing for contexts that one is not familiar with. Given the range of international students in our program, perhaps this is a next step in the evolution of our briefs.

Embracing and exploring the third E of equity, while never sacrificing the other Es, is the goal of NYSID’s MPSS program, and indeed should be the goal of sustainable design more generally.

The three Es are sometimes referred to as the legs of the sustainability stool. Until now we’ve had a lopsided three-legged stool that leans to one side. The equity leg needs to be lengthened, all the while adding the fourth leg of esthetics.

A four-legged stool, if the legs are uneven, may be more off-balance. But it also, perhaps counterintuitively, is more stable in that it is less prone to falling over. The trick is to make those four legs as equal as possible, not emphasizing one leg over the others.