Story at a glance:

Heavy rainfall, increased fires, high winds—most American adults have been negatively impacted by extreme weather events since 2019, and most say their communities are not prepared to withstand climate change. That’s not hyperbole. That comes from a 2022 US Climate Action Survey by Gensler.

“The majority of the US population is convinced climate change is real. The vast majority have been impacted recently—within the last two years—by what might be a climate event,” says Rives Taylor, global design resilience co-leader and principal at Gensler.

People were not only saying they were impacted, but they’ve been impacted multiple times.

The survey found that 87% of US homeowners reported being negatively impacted by extreme weather since 2019. More than 80% said they were open to making changes to their homes (cost being the biggest barrier), but only 18% believed their communities were built to withstand climate change.

A key theme of the report is the opportunity for developers and planners to incorporate design resilience strategies to minimize the negative consequences of climate change on people and the environment. The report’s data is based on two online surveys of 2,756 US adults between October 30 and November 1, 2021. The studies were conducted via an anonymous, panel-based survey. “People were not only saying they were impacted, but they’ve been impacted multiple times,” Taylor says.

Losing power and connectivity during these events was a major concern, Taylor adds. The internet goes out and people can’t work at home, or roadways aren’t passable so people can’t get to work or school or even the store. Respondents worried about the uncertainty that comes with increased storms and their quality of life.

In part the survey asked homeowners what they had done and what they would do to make their homes more stable—whether that was to install a smart roof, consider their building envelope, or add a backup generator, for example. Cost and knowledge were the top reasons why homeowners hadn’t already implemented these things. While respondents didn’t indicate that they’d uproot, they did report extreme weather events were starting to shape behavior like real estate purchases and housing modifications.

Gensler is working to share these findings with the wider industry, including the steps they believe must be taken to minimize carbon-based climate impacts. The US Climate Action Survey 2022 serves as a framework for how the real estate industry can make immediate investments to lower its carbon footprint and improve the relevance, insurability, and value of all property types.

“This climate conversation is also very much about materials,” Taylor says, pointing to the historical houses on the coast that still stand because they were built to hold up to the elements. Unfortunately, he says many of the building materials chosen over the last 60 or 70 years are of lesser durability, as contractors began using the same materials across projects without considering a project’s location—like whether it’s on the coast or landlocked, for example.

While storms certainly affect human safety and well-being, Taylor says it’s also important to consider the impacts on businesses who want to quickly “bounce back.”

Gensler’s transformation of the Arizona Center creates a new model for office, retail, and entertainment in Phoenix. Upgrades focus on unveiling the previously introverted development into a vibrant, extroverted experience that connects to the existing urban fabric through the design of gateway features, visible graphic identification, and thoughtful strategic planning. Photo by Bill Timmerman

Responses to things like flooding have changed as a result of material and design choices, too. Decades ago, if solid wood floors got wet inside a house, you opened the windows and took the rugs outside, letting materials naturally dry, Taylor says. But if you have wall to wall carpeting and drywall walls, you have to rip up the damage to make repairs.

“We’ve chosen to create an interior environment that isn’t very smart,” Taylor says of many of today’s designs. “We need to rethink how we make everything that could get wet. Look at Venice. It gets wet, and yet it’s still there. They don’t take out drywall, they have plaster or masonry walls. They think differently about materials where there’s water. We’ve got to rediscover that.”

He says instead of drywall, there’s plaster or earth plaster, for example. And for flooring, solid wood plank or terrazzo or stone. “It’s the idea of designing in a way that recognizes that if it gets wet, you can quickly recover rather than throwing things away,” he says. He notes that being able to open windows, though, is also critical, and not just after a storm. “We learned that in the era of Covid—buildings that are totally sealed in may not always be smart when we don’t have power. We need cross ventilation. Can we rethink how we get air ventilation if the power goes out?”

Taylor wants to look at making buildings livable for longer in the event of a power outage, recalling the recent major power crisis suffered in Texas where he lives in February 2021. He wants to make sure buildings are designed to have systems that allow for a more orderly temporary shutdown that lets people get back to work or back home quickly.

“It’s an operational mindset as much as a design mindset. But in my 10 years-plus of being an operator, our goal was to get things going in a safe way very quickly after the event passed. And that meant making some strategic decisions about design and operation.” It’s all about fast, pre-planned recovery, he says.

Designing Green Communities

Multiple urban portals at the Gensler-designed Arizona Center were created to direct pedestrian circulation toward the project’s central core and encourage impromptu social gatherings. With the new open entries, walkability increased dramatically. Dramatically patterned perforated metal screens integrate with existing facades. Photo by Bill Timmerman

Native plants ornament the welcoming entry ways and the urban plaza at the Arizona Center. As you reach the central plaza, southern live oak trees line the outdoor seating areas to provide a sense of place and, eventually, to be a main source of shading. As the vegetation grows, the space will become more of a haven for guests to find tranquility in the middle of downtown Phoenix. Photo by Bill Timmerman

Taylor says designing green communities is a crucial piece of the puzzle—and that goes beyond buildings. Green spaces soak up water and keep neighborhoods cooler while providing obvious health benefits like getting fresh air to residents. It’s important to make sure those exist in every neighborhood, he says.

He says low impact design is also important. “We need to design neighborhoods that have a place for stormwater and rainwater to go,” he says. “Low impact design strategies are really gaining traction in places like Arizona and Houston, where there’s more of the urban heat island and the occasional gullywasher.”

Gensler looks at this as an opportunity to rethink the urban landscape, from stormwater control to shading and public green space. The firm recently partnered with the Florida International University School of Architecture to teach a class focused on researching coastal climate challenges in major US cities to develop a framework for local partnerships to scale the development of responsive design strategies. Together with masters’ students, they identified current risks and projected vulnerabilities due to sea level rise and climate events in Washington, DC, New York City, Houston, Boston, San Francisco, Tampa, London, and Miami. In Miami, almost 2 million people live within storm surge areas—many without the resources to recover from property loss.

To mitigate the risk of rising water in Miami, Gensler identified the following strategies in its report:

1. Create pedestrian accessibility. A network of pedestrian green routes connect the neighborhoods and large parks at the coastal edge and in the center of the development.

2. Provide green and blue views. Maximize views of green space and water by ensuring the development steps down in height from the dense core to the shoreside neighborhoods.

3. Create “sponge roofs” and permeable pavements. A mix of green roofs and permeable pavements support a sustainable drainage system strategy to capture and store water.

4. Collect rainwater and graywater. Sponge roofs paired with siphonic drainage and a storage system collect rainwater and significantly reduce water usage in a property when combined with graywater from sinks and showers.

To mitigate heat in downtown Phoenix, Gensler developed an experience-based, pedestrian-oriented model for the Arizona Center, a mixed-use office, retail, and entertainment venue:

1. Add shade. Vertical and horizontal envelope-mounted sun screens and deep roof eves can shade buildings and the sidewalk below.

2. Replace concrete and asphalt. Permeable pavers absorb much less heat than asphalt.

3. Use native landscaping. Native trees and shrubs on top of and around buildings serve as added shade while capturing stormwater runoff.

4. Partner with local communities. Education and outreach on a local level can raise awareness of the harmful effects of heat. Offering practical and actionable solutions like volunteer tree planting efforts or weatherization instruction can engage the community and lower the temperature.

Choosing the Right Roofing

Products like EcoStorm VSH will not disintegrate or delaminate in the presence of water. Photo courtesy of Carlisle Construction Materials

Even insurance companies are acknowledging extreme weather, making modified requirements for things like hail over the last few years, according to Craig Tyler, manager of specification development and green initiatives at Carlisle Construction Materials.

Climate change is altering the pattern of hailstorms, according to reports from the BBC, who reported broken records for the largest hail in the last three years in Texas, Colorado, and Alabama—with hail reaching up to 6 inches in diameter. Hail damage in the US now averages more than $10 billion a year, according to the BBC.

Tyler, who’s been with Carlisle 10 years and is a licensed architect and LEED AP, says hail is showing up in more unlikely places, too—from Montana to Texas to North Dakota and everywhere in between. “They’ve definitely increased their requirements to get the insurance coverage you need to beef up the roof system to protect itself from that kind of damage.”

Resilient Design

EcoStorm. Image courtesy of Carlisle Construction Materials

Tyler attends code hearings where building code is updated every three years, and most recently he’s watched as codes were added to protect not just for West Coast fires, but now for flooding from events like tsunamis and earthquakes that create large waves that impact coastal areas.

“There was no code requirement for having an evacuation spot that’s higher up in the building, where before if it was a fire, you’d go down to the ground to get out of the building. What if it’s a flood? We need to have protection on the lower floors to strengthen the building, obviously, but also areas higher up for people to take refuge who may be living on the first or second floor who would be impacted by water.”

With more tornadoes and stronger hurricanes, Tyler says the first mission should remain to protect building occupants, but just as Gensler’s Taylor said, you also want to protect the building so it can be occupied quicker later and hold up during a storm.

Tyler defines durability as knowing your interior walls, for example, are going to get “beat up” so you use better materials to protect from impact. For example, in a busy hallway you might use concrete block or brick instead of drywall. He describes resiliency as that added layer, accounting for the unexpected. “We want to be able to return the building to a serviceable state very quickly,” he says.

If a tornado rips a roof off a building, it’s going to take a long time before people can get back to work at that building, from insurance claims to getting materials to the job site to fixing the roof itself. “In resiliency the idea is to have redundancy as well as durability. You’re also making decisions to make sure it’s able to be repaired quickly or easily.”

Designing buildings with thicker roofing membranes and strong coverboards with more PSI directly beneath those membranes adds more protection—durability and resiliency. This helps protect not only during a storm (especially protecting against severe hail) but also if there’s increased foot traffic on the roof—be it for HVAC repair, solar work, or if it’s a rooftop with public amenities.

“If it’s a better coverboard and it has a higher impact—maybe it’s four-inch hail balls or a storm launches some debris on the roof like branches and other debris—the first step is to protect the roof as much as you can,” Tyler says.

Products like EcoStorm VSH, for example, will not disintegrate or delaminate in the presence of water. EcoStorm VSH is an engineered composite building material made from a proprietary blend of plastic and cellulose fiber sourced from post-industrial and post-consumer waste streams. It’s durable and extremely moisture- and mold-resistant. The EcoStorm VSH coverboard is a 100% recycled board made from waste like milk cartons and plastic bottles. It also has pending FM Very Severe Hail (VSH) approvals, and an ultra-high compressive strength of 3,990psi.

Coverboards in the gypsum family are heavy and dense, so they make great coverboards, Tyler says, but they do take a bit more time and labor considering their weight. Carlisle developed a high density polyiso insulation that’s much lighter—SecurShield® HD Polyiso. “It’s faster to install and uses less materials,” he says.

Tyler recalls a recent project that used Carlisle’s FleeceBACK RapidLock (RL) system with Velcro Brand Securable Solutions. It stood up to 140 mile-per-hour winds during a test. The membrane attachment method provides a fully adhered EPDM, TPO, or PVC system without the use of adhesives. “It’s more like permanent Velcro,” he says. It’s performed well in the field, too, as Tyler recalls one contractor saying that of multiple buildings in one area whose roofs needed repair after a storm, the one with this system needed no repair.

Green Roofs

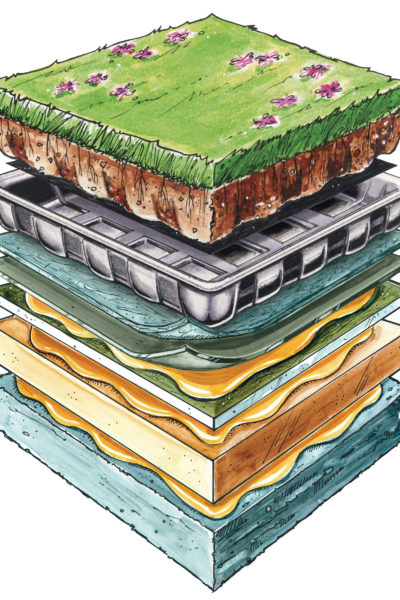

Photo courtesy of Carlisle Construction Materials

Roof gardens have long been popular, but beyond beauty and biophilia, they also offer storm protection. In a torrential downpour, you could have four inches of rain coming off a roof and draining into a sewer system. A green roof, however, slows that down and even holds water to help plants grow and prevent further flooding below. Without a green roof, you may get more water backed up on sidewalks and streets.

“A roof garden application is going to hold a lot of that water first,” Tyler says. He says cities with older sewer systems like Philadelphia, St. Louis, and Washington, DC increasingly turn to green roofs for help.

GreenGrid modular roof garden assembly. Drawing courtesy of Carlisle Construction Materials

“Pittsburgh Convention Center has a beautiful roof garden combined with pavers,” Tyler says, noting that they worked with Carlisle on the project. Their green roof is one story below the main roof for public access and special events like fundraisers. It’s an added amenity, he says.

“That’s become really popular in bigger cities, too. You’ve got hotels like Hilton and Marriott who are doing these rooftop bars where they use a lot of pavers so you can walk on it, but then they’re also incorporating plants or roof gardens.”

Designing with Excellent Exteriors

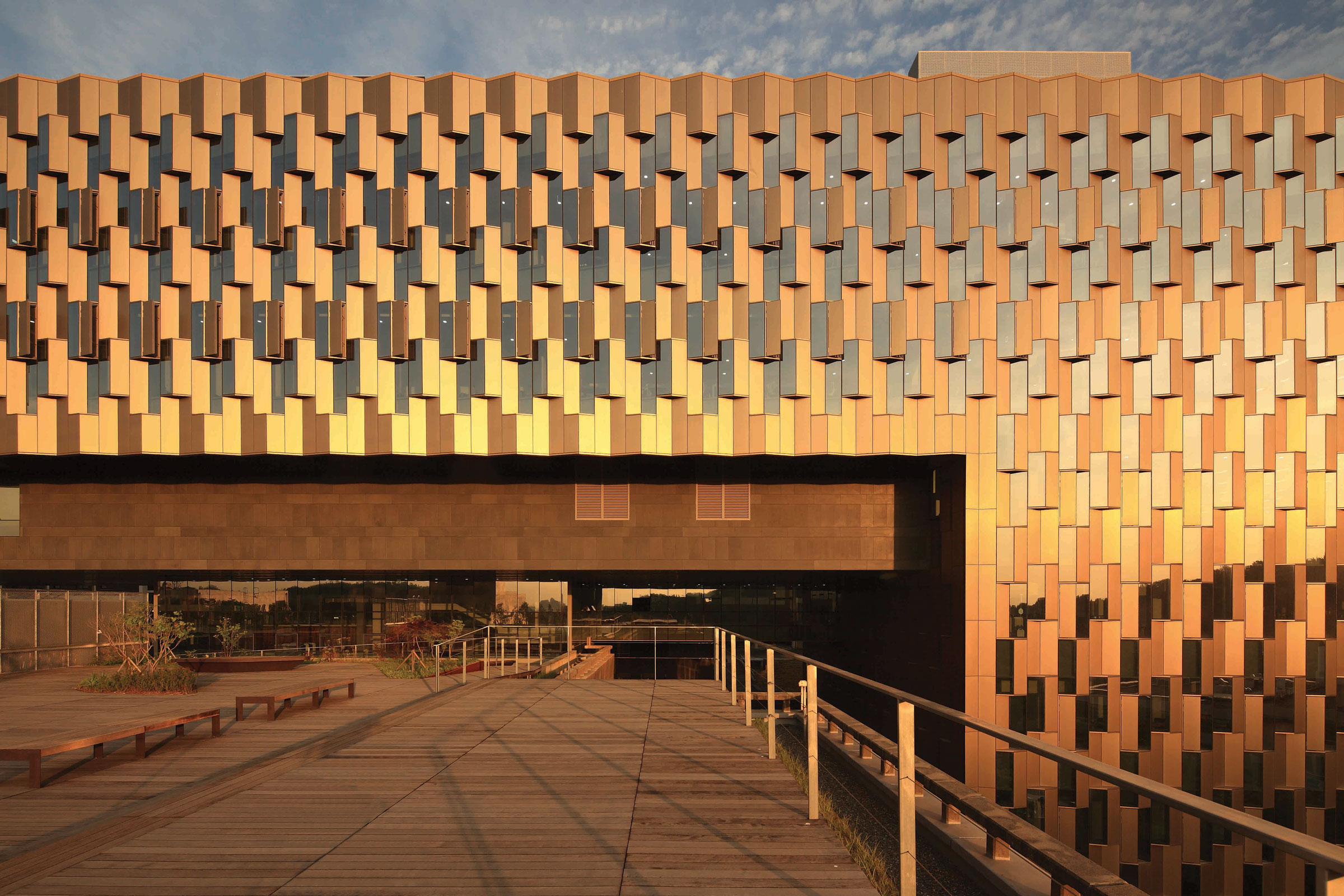

Lorin exterior. Photo by Kim Jong Oh

From the Superdome in New Orleans to a church roof in Michigan that’s more than 35 years old, anodized aluminum exteriors have proven to stand the test of time, says Phil Pearce, vice president of sales and marketing at Lorin.

Pearce, also a LEED AP, says building responsibly has always been important to him—and to Lorin. He says anodized aluminum outperforms paint for salt spray and other wear resistance tests, and it holds up in tough storms. “It can’t chip, flake, peel, or chalk like paint because it’s literally bonded at the molecular level,” he says. “It really is very, very durable.”

After Hurricane Katrina, the New Orleans stadium’s architects were looking to match the original anodized material because it was so durable, Pearce says. But because the aluminum had been “batch” anodized rather than anodized using a continuous coil process, they ultimately went with Lorin to ensure decades of color consistency.

Photo courtesy of Lorin

“We really invented the continuous coil form of anodizing,” Pearce says, adding that Lorin has been refining the process to make it even more beautiful since the early 1950s. “We can deliver a high-quality product that will not only last a long time but will look consistent over the long haul.”

Pearce says the continuous coil anodizing process makes the aluminum more abrasion- and weather-resistant. “Anodized aluminum is used in many marine/boating applications precisely because it is so good in the salt air environment,” he says. Lorin has a minimum warranty of 20 years.

Many architects may also turn to anodized aluminum because aluminum is lighter, so it’s easier to handle. Because of its superior formability and tighter tolerances than other metals, aluminum also offers more profiles for roof panels, Pearce says. He says the same tools used for steel can be used for aluminum in the field.

“Anodized aluminum is lightweight, it’s very durable, and it’s malleable,” he says. “And because of the variety of its applications and forms and finishes as well as better manufacturing tolerances, aluminum can be made into more profiles, or shapes compared to other metals that can help architects create really unique solutions to match their vision while meeting the structural and functional needs of the building.”

He says its high strength to weight ratio makes it ideal for forming and meeting the challenges of managing curved and double curved architectural designs.

Austin Public Library exterior. Anodized aluminum comes in a variety of colors, shades, and finishes.

Photo courtesy of Lorin

Aluminum on its own is a naturally corrosion-resistant material, so it weathers well, but once anodized it’s even more durable. When considering its performance in a fire, Pearce says anodized aluminum is also a very good material because it’s non-combustible. “It really doesn’t burn like other materials might,” he says.

In today’s climate of Covid supply chain shortages, anodized aluminum is similar in price—if not less—than PVDF paints, Pearce says, and it’s readily available, whereas he says PVDF paint supplies are currently limited.

ClearMatt Series

Pearce says there’s an increased desire in architecture today to use natural metals rather than covering natural metals with paint. Because ClearMatt® is a translucent, natural matte anodized aluminum, architects can get the look they want. “Anodizing aluminum builds the crystalline structure that reflects and refracts light in a way that helps the building come alive and creates a three-dimensional metallic look you just can’t get from paint, as paint covers up that natural metal look,” Pearce says.

ClearMatt lets you celebrate the natural look. Alternatively, if you do want to add color, Lorin can introduce color into the pores without covering up the metal. It can also take on the look of zinc, titanium, copper, or bronze. “It can look like those other natural metals without having to go to the added expense of using those other metals or adding weight,” Pearce says.

In addition to ClearMatt, Lorin’s ColorIn® series of bronzes and black, AnoZinc® colors, and shades of Champagne and Gold also hold up well to weathering. You won’t have to worry about the patina effect over time with UV stable finish colors.