Story at a glance:

- Sustainable equitable design focuses on community, aiming to address disparities in access and social inequities and support meaningful physical and social transformation.

- These institutions stand at the intersection of history, culture, and resilience—yet face persistent challenges in facilities, funding, and student support.

Designing for equitable communities is an essential element within the framework of design excellence. In the context of sustainability, it is where its two pillars—environmental and social—come together.

Organizations like the USGBC have advanced this by introducing the concept of sustainable equitable design. The intent is to approach social equity from a community-focused mindset, address disparities in access and social inequities, and support meaningful physical and social transformation. Effective engagement and relevant needs assessments are critical for sustainable, equitable design to be successful.

The Project Team’s Role

Meaningful transformation comes through change in behavior and systems. It takes time to build relationships and trust.

The first step is to listen, understand, and identify the unique factors contributing to inequity. The project team can promote and advance social equity by following principles that address disparities:

- Creating fairer, healthier, and more supportive environments for those who work/live in the project’s area.

- Promoting fairness, respect for human rights, and other equity practices among disadvantaged individuals and communities.

- Providing opportunities for those affected to have a greater voice in decisions that impact them.

- Responding to the surrounding community’s needs and promoting a fair distribution of benefits and burdens.

Planning and designing for Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) offers an opportunity to illustrate challenges to listen to and the opportunities to act on to make sustainable, equitable design a reality.

The Importance of HBCUs

The Supreme Court’s 2023 decision to end Affirmative Action in campus admissions and other recent administrative considerations has led to an influx of enrollment in HBCUs. HBCUs make a concerted effort to offer an affordable college experience.

In 2022 the National Center for Educational Statistics (NCES) reported that tuition and fees for in-state students at HBCUs cost $9,900 per year, compared to around $11,160 for in-state learners at all higher ed institutions, according to Forbes. Of those enrolled, 52% of HBCU students are first-generation college students, many coming from lower-income backgrounds.

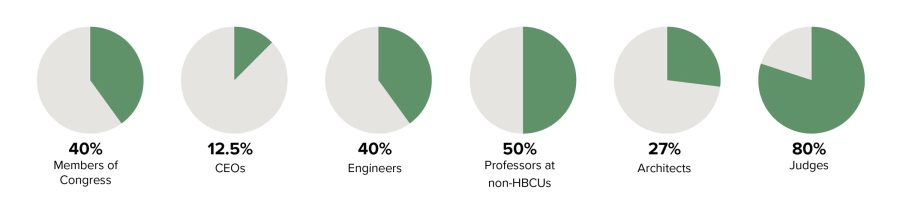

According to the Thurgood Marshall College Fund, in terms of outcomes, among African Americans, HBCU graduates equaled:

Data as according to Thurgood Marshall College Fund, courtesy of Sizemore Group

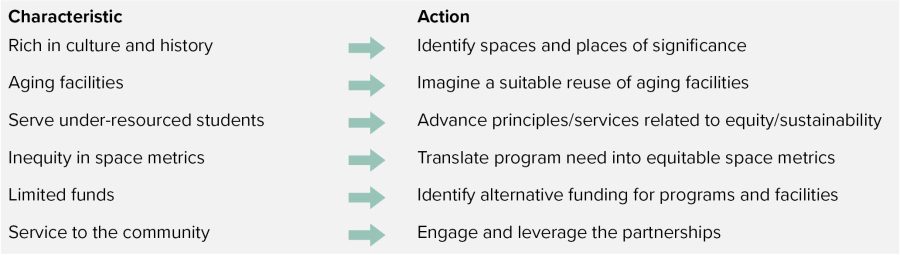

HBCUs have distinct characteristics that project team members should track and be able to act on as opportunities to bridge gaps that emerge throughout the process.

Image courtesy of Sizemore Group

Here are some ideas project team members can apply when working with HBCUs:

- Abide by principles regarding equitable design recommended by AIA, USGBC, and other organizations.

- Pay special attention to the history and cultural elements of the campus. Create opportunities to celebrate distinct cultures and traditions.

- Identify the essential functions for underserved students to succeed and the type of spaces or places that best support these.

- Reimagine how existing facilities can meet future needs.

- Include the campus and external community as stakeholders. Their voices are important, and opportunities for partnering and adding resources may surface.

By their historic designation, these institutions have a higher portfolio of facilities that are more than 75 years old and may have cultural or historic significance. When retained for their significance, they will need maintenance, renewal, and a new vision for how to best serve current and future constituents. Practical solutions call for creative ways to fit new functional needs within the form and character of the facility.

The need to address under-resourced students requires additional academic or student support functions. External programs like TRIO that focus on student success bridge the gap in student retention by providing services that require more staff and space. Standard metrics for space use in higher education (and K-12) do not recognize what they need. The project team should be prepared to define, present, and justify these functions.

Because of limited funding, the process must help identify various sources or partnerships to fund the initial capital investment, maintenance, reduce operation, or a combination of these. This is important, particularly for private HBCUs.

The following are examples of the challenges and opportunities acted upon, and the outcomes yielded when applying processes geared toward meaningful transformation at HBCUs.

Savannah State University

Morgan Hall. Photo courtesy of Sizemore Group

Savannah State University (SSU) is the oldest HBCU in Georgia and is located along the edge of Savannah’s coastal marsh. More than 20% of the academic and administrative buildings are more than 75 years old, most located around Alexis Circle, where the original campus resided until 1966 when it expanded west across a canal. An additional 46% of the buildings are more than 50 years old.

The challenges of these older buildings include a large amount of deferred maintenance, repair, and renewal, coupled with space not in use or apparently needed when applying the industry’s space utilization metrics. Measures taken to bridge gaps included recalibrating the standard space metrics to include space for services like TRIO and others that advance student retention and progression.

This transformed the application of the traditional metrics at SSU and has allowed for similar consideration at other public higher education institutions. In addition, creative thinking has led to the reuse (recycling) of facilities like Morgan Hall, where those unique services fit in a welcoming space that leverages natural light, energy-saving lighting, and equipment, all reducing the cost of operation.

Atlanta University Center Consortium

Thayer Hall. Photo courtesy of Sizemore Group

The Atlanta University Center Consortium (AUCC) is in the center of Atlanta and is a vehicle for partnerships and collaborations between four HBCUs—Clark Atlanta University, Spelman College, Morehouse College, and Morehouse School of Medicine.

AUCC evidences each HBCU’s common interest in serving the others and their surrounding community. They collaborate in initiatives beyond their boundaries and share resources—including a library, shuttle service, and a central plant.

As SSU they have a facility portfolio with a higher percentage of historic/cultural significance, deferred maintenance, and need space for programs that do not fit the industry’s units of measurement but are essential to the success of their students. For private institutions, public funding may only come from federal programs, and as such, there is a limit to the amount available for capital investment.

Clark Atlanta University

Image courtesy of Sizemore Group

Clark Atlanta University initiated a plan to address the issues above within the context of consolidating academic units. They were also considering the disposition of an old central plant—either replacing it with a new one or moving to standalone building systems throughout, a decision that impacted three institutions. As part of the planning process, our project team sought conversations regarding how small federal funds to improve academic space could be combined with larger capital investments.

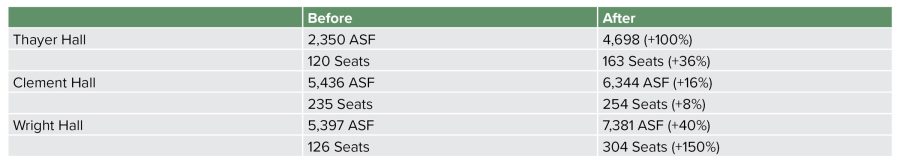

The decisive action plan developed by the team for Clark Atlanta included augmenting their funds with any federal funds available to improve academic space. Those funds were invested in buildings that contributed to their history and culture and could house the consolidated colleges. The project team members created distinct construction packages to leverage funding cycles and aligned reporting of the type of spaces renovated based on the requirements for external funding. Such is the case with Thayer Hall, the original dining hall, whose main dining area now houses teaching.

As a result of using this strategy, the university completed three major renovations, among the first LEED interiors for HBCU, increased the amount of occupiable space and seats for academic and student support, and reaped the benefits of reduced energy consumption.

Spelman College

Photo by Tom Harris, courtesy of Spelman College

Conversations with the AUCC and other community members uncovered that Spelman College was considering expansion plans that included a makeover of their residential portfolio, a new quad, and an arts center. The potential for added capacity and redundancy of a new central plant was an important consideration for all and eventually led to a ‘go ahead.’ Within three years the institutions reported savings in operating costs.

Spelman College completed phase one of its development, which includes the Spelman Suites residence hall, the first LEED residential hall in an HBCU, and the quadrangle. Additional renovations have proceeded.

Most recently the final piece for this sector plan, the Mary Campbell Schmidt Center for Innovation and the Arts, designed by Studio Gang, opened for use.

Planning and designing for HBCUs offers a unique opportunity to align physical transformation with social equity. These institutions stand at the intersection of history, culture, and resilience—yet face persistent challenges in facilities, funding, and student support. By adopting a process rooted in empathy, collaboration, and innovative thinking, project teams can help HBCUs thrive and continue their critical mission. A commitment to deeper engagement, purposeful design, and strategic partnerships that honor the legacy of these institutions while shaping their sustainable future is imperative.

Art Frazier, director of facilities management and services at Spelman College, contributed to this article.