Story at a glance:

- Historic preservation in architecture seeks to preserve and protect buildings that possess a strong cultural, economic, social, or architectural history.

- Preserving historic buildings helps to prevent demolition waste, protects the historic fabric of an area, and creates a record of past building materials and techniques.

In the United States historic preservation, or the process of protecting historically significant buildings, has been practiced in some capacity since at least the late 1800s. Historic preservation would, however, become much more commonplace after Congress established the National Historic Preservation Act in 1966, which created the National Register of Historic Places and mandates the active reuse of historic buildings for public benefit and the preservation of our national heritage.

Let’s explore the basics of historic preservation in architecture and explore a few real-world examples.

What is Historic Preservation in Architecture?

Michael Graves reinterpreted classical elements such as pilasters, garlands, and keystones in his design of the Portland Building. Installed in 1985, Raymond Kaskey’s Portlandia sculpture is the second-largest copper repoussé statue in the United States after the Statue of Liberty. Photo by James Ewing

Historic preservation architecture, or built heritage conservation, is a subset of architecture focused on preserving, protecting, and conserving buildings and structures with sufficient historical significance. In most cases historic preservation prioritizes the maintenance, repair, and reuse of a building’s existing materials, features, and elements rather than replacing, altering, or otherwise adding to a structure.

Historic preservation is closely linked to the notion of adaptive reuse, or the process by which existing buildings are renovated, refurbished, or otherwise updated to serve a purpose other than what they were originally designed for. While adaptive reuse is not a requirement for historic preservation, the two often overlap, as it is often possible to adapt the usage of a building without seriously impacting its historic character.

Preservation is one of four treatment standards identified and defined by the US Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for the Treatment of Historic Properties, with the others being rehabilitation, restoration, and reconstruction.

- Preservation. The process of applying measures necessary to maintain the existing form, integrity, and materials of a historic property, as opposed to replacement or new construction; electrical, plumbing, mechanical, and other code-required changes are supported if necessary for the building’s continued function, but exterior additions are not permitted.

- Rehabilitation. The act of making repairs, alterations, and/or additions to a property to better suit new or changing needs while still preserving those features that accurately convey its historical, architectural, or cultural values; acknowledges that certain features may need to be altered or added to meet current needs.

- Restoration. The process of accurately depicting the form, features, and details of a building or structure as it appeared at a specific point in time by reconstructing missing features from said time period and removing those features from other periods in the property’s history.

- Reconstruction. Defined as the act or process of depicting via new construction the form, features, and details of a building or structure that no longer exists, for the explicit purpose of replicating its appearance at a specific point in time.

For the purposes of this article and its examples, the term “historic preservation architecture” encompasses both preservation and some rehabilitation projects, as the two treatments are fundamentally interrelated; a rehabilitation project may, for example, preserve certain features while also making alterations that allow the building to better serve the needs of the community.

Why is Historic Preservation Important?

Historic preservation is important because it helps to extend the operational lifespan of historically or culturally significant buildings that would otherwise languish in abandonment or be demolished to make way for new development. Not only does this help protect local histories and add to the historical fabric of an area, it helps to create an architectural archive of sorts, one that acts as a record of past building techniques and strategies.

“Extending the lifespan of a building preserves examples of construction materials and methods that are being forgotten,” Ellen Tichenor, creative director at Thrash Group, previously told gb&d. “And preservation of urban historic fabric contributes to the cultural identity and quality of life of a place.” Historic preservation architecture is also important from a sustainability standpoint, as it drastically reduces the amount of construction and demolition waste sent to landfills.

10 Examples of Historic Preservation in Architecture

Here are some recent examples of historic preservation in architecture, from historic universities to hospitality projects and apartment living.

1. MSU Romney Hall, Bozeman, MT

Romney Hall embodies the Italian Renaissance Revival style with a beautifully detailed tapestry-brick facade featuring terra-cotta spandrels decorated with athletic motifs, large wood and steel windows, copper detailing, and a barrel-vaulted metal roof. This iconic building contributes significant historic value to the Montana State University Historic District and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Photo by Karl Neumann

Built in 1921 as a physical education building for Montana State University (MSU), Romney Hall largely fell out of use in the 1970s after the university built new athletic facilities. To make the most out of its square footage, Romney Hall was renovated in 2022 and now houses additional offices and lab spaces for MSU’s College of Education, Health and Human Development.

Romney Hall’s renovation was led by Cushing Terrell, whose project goals included preserving the building’s Italian Renaissance Revival style while improving accessibility, sustainability, and overall safety. A historical preservation and structural analysis of the building was conducted and the firm began designing as the interior was being demolished to better understand what materials could be reused. More than half of the building’s original resources and materials were preserved and reused, including structural elements, enclosure materials, and permanently installed interior elements.

Marble wall panels were repurposed as decorative elements and shower stalls, while the building’s original terrazzo floors in the north stair—itself preserved as a character-defining feature—were cleaned and restored to their original condition. Hardware and suspension rods were also left exposed and inspired the metal components for the new walkway, stairs, and guardrails.

2. Carleton University Loeb Building, Ontario

The Carleton University Loeb Building includes a new active student space designed by CSV Architects. Photo by Krista Jahnke Photography

Built in the 1960s as a student space, the Loeb Building at Carleton University in Ontario was renovated by CSV Architects in 2019 to better serve the university’s needs without getting rid of the historic elements that gave the building its character.

“Throughout the design process the intention was to pay respect to the existing exposed brick and concrete surfaces of the building and complement with carefully selected new finishes and colors,” Rick Kellner, associate at CSV Architects, told gb&d in a previous article. “The exposed brick walls and waffle slab ceiling were refreshed by applying white paint, instead of being concealed behind new finishes. The new finishes that were installed—including flooring, wall panels, and glass boards—complement the brick and concrete surfaces and highlight the original millwork of the building.”

Existing wood-framed windows—all more than 50 years old—were repaired and refurbished, a process that included the delicate refinishing of existing wood trim in places as well as the select removal and replacement of pieces when necessary. CSV even went so far as to ensure new staining matched the building’s existing window frames and trim finishes in order to maintain a cohesive historic patina between new and old elements.

CSV also implemented flexible room layouts to allow the Loeb Building to evolve and adapt as needed, introducing biophilic design elements like a wood slat ceiling and greater exposure to natural sunlight to create a space that actively fostered wellness, collaboration, and learning for both students and staff.

3. Hotel Morgan, Morgantown, WV

The restored Hotel Morgan dates back to 1925 and was a popular spot for dignitaries. Photo by Chase Daniel

When it first opened its doors in 1925, Hotel Morgan was the epitome of elegance and quickly became the place to stay in town, attracting everyone from professors and the parents of local college students to former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt and President Harry Truman.

Over the years, however, the hotel became less and less a destination for professors and presidents and more a spot where the local college football crowd would congregate, leading to a renovation in 1999 that sought to update the design to suit modern tastes. In 2020 Hotel Morgan was renovated once again, this time by the Thrash Group and Vertikal Collaborative, with the intent of returning the building to its original splendor, albeit with a modern twist.

Hotel Morgan’s redesigned guest rooms blend modern design and with timeless details. Photo by Chase Daniel

“As the architect, the goal was to restore the timelessness and sophistication that we imagined the original lobby offered guests,” Sarah Newton, an architect with Vertikal Collaborative, previously told gb&d. “A lot of elements had already been replaced, in which case we either kept them if they were still operable and contributed to the restoration efforts or replaced them to what we thought was originally there based on what would have been there at the time the building was originally constructed.”

All of the original components that were still in place—including, original wood windows, tall steel windows, tile floors, and wooden trim/finishes—were kept and restored wherever possible, with modern amenities strategically inserted alongside them. Vintage Victrola radios, retro refrigerators, chaise lounges, and large, luxurious bathrooms can be found in each of the hotel’s guest-rooms and suites, all of which are furnished with custom pieces designed by Thrash Group.

4. Cable Mills Apartments, Williamstown, MA

Cable Mills Apartments houses 61-residential units and occupies eight buildings originally constructed as part of the General Cable/Water Street Mill complex. Photo courtesy of Cable Mills

Originally built in 1873, the General Cable or Water Street Mill in Massachusetts got its start manufacturing twine, and later, wire and cable. As the demand for these products gradually declined throughout the 20th century, however, the mill became obsolete until it was finally forced to shut its doors in 1996.

In the early 2000s the mill complex—a total of 15 structures—was acquired by the Traggorth Companies LLC, who sought to transform eight of the buildings into residential apartments. Over the next 14 years and with the help of local architectural firm Finegold Alexander Architects, their goal was finally realized in the 61-unit Cable Mills Apartments housing complex.

Photo courtesy of Cable Mills

All of the original exterior brick cladding was preserved, along with 20 types and sizes of windows across multiple buildings. Inside, exposed brick walls give the units character while high wood-beamed ceilings, polished concrete floors, and contemporary finishes seamlessly blend the old with the new. Energy- and water-efficient appliances and systems were also installed, greatly improving the project’s overall sustainability.

Finegold Alexander Architects’ exemplary renovation of the Cable Mills Apartments was recognized by Preservation Massachusetts and the project received the Paul & Niki Tsongas Award – Biggest Impact Rural/Suburban in 2017.

5. Boston Public Library’s Boylston Street Building, Boston

William Rawn Associates breathes new life into one of the country’s most beautiful libraries. Photo courtesy of William Rawn Associates

Built in 1972 and designed by architect Philip Johnson, the Boylston Street Building is one of two buildings that make up the Boston Public Library’s (BPL) Central Library in Copley Square, with the other being the original McKim Building, built in 1895. The Boylston Street Building underwent an extensive renovation between 2013 and 2016 in order to better serve the community’s needs and strengthen its connection to the city as a whole.

Because of the Boylston Street Building’s status as a local landmark, BPL, the City of Boston, and William Rawn Associates (WRA) worked closely with the Boston Landmark Commission to ensure retention of the building’s defining features and conformity with Johnson’s original vision.

“We read everything we could find about Johnson’s work and from that developed a set of Johnson Principles,” Cliff Gayley, a principal architect at WRA, told gb&d in a previous article. “These principles included his ideas like the nine-square grid as well as procession and moment of arrival. We also found specific statements and criticisms Johnson made about his original building that we could address. These principles guided how we thought about transformation as we, the library, and the city worked closely with the Landmarks Commission and their staff to achieve fundamental change, while respecting the legibility and integrity of the original building.”

Photo courtesy of William Rawn Associates

Using these guiding principles WRA was able to strategically remove dividing walls and mezzanine floor plates to create a unified two-story space spanning the length of Boylston Street that now includes a cafe, broadcasting studio, digital labs, lecture halls, a teen room, and more. A series of 10-foot-tall granite barricades that blocked the library’s interior from the street were also removed in order to accommodate new entryways and open the building up to the street. Large floor-to-ceiling windows were added in place of the original dark-tinted glass and stone walls, increasing admittance of natural sunlight.

In 2017 the Boston Public Library and a conservation team led by Gianfranco Pocobene would go on to win the Preservation Achievement Award from the Boston Preservation Alliance in recognition of the team’s efforts to preserve and restore artist Pierre Puvis de Chavannes’ Philosophy panel, one of several murals decorating the library’s grand staircase. In the same year, the library received joint awards from the AIA and ALA for its renovation of the Boylston Street Building.

6. Portland Building, Portland

The postmodern Portland Building is one of the city’s icons. In a reconstruction led by DLR Group, a new curtain wall system solves longstanding water leakage issues, while improving thermal performance and increasing access to natural light. Photo by James Ewing/JBSA

Designed in 1982 by Michael Graves Architecture & Design as a light-hearted response to the formality of modernist architecture, the postmodernist Portland Building has never lacked whimsy or expression, but it did lack natural sunlight and adequate insulation. Plus, it leaked whenever it rained. These problems were largely attributed to the use of low-quality materials in the building’s construction, a byproduct of the budget constraints that plagued the project from start to finish.

When DLR Group was brought in to renovate the building, they had to find a way to preserve Graves’ design intent while also addressing its technical shortcomings. “Preservation usually puts a lot of focus on maintaining historic materials,” Erica Ceder, an architect at DLR Group, previously told gb&d. “One of the really challenging parts about the Portland Building is what do you do when there are inherent flaws in the way the building was put together in the first place.”

To remedy these flaws DLR Group elected to install unitized curtain wall panels over the existing cladding system, drastically improving the building’s thermal performance by shifting the insulation layer to the outside of its concrete shell. The teal tiles at the base of the Portland Building were replaced by a terra-cotta rainscreen system that greatly reduced the possibility of water intrusion. Both the curtain wall and rainscreen were designed to replicate the materials they replaced and were painted to match the original color scheme.

The Portland Building’s daylighting problems were solved by replacing the existing aluminum-framed windows—which were inefficient and used a darker glass that only let in about 7% of the natural sunlight—with thermally broken, energy-efficient windows that let in closer to 80% of the light. An interior parking lot entrance was also removed and replaced with a two-story glazed window that brightened the lobby and strengthened its connection to the outdoors.

Insid, the design team removed drop ceilings and exposed the waffle slab underneath, opening up the interior and giving it a more comfortable scale. Conference rooms and private offices located around the building’s perimeter were also moved further inwards to free up valuable window space, while standardized hardwall rooms were installed throughout to provide long-term floor-plan flexibility.

7. Beloit Powerhouse, Beloit, WI

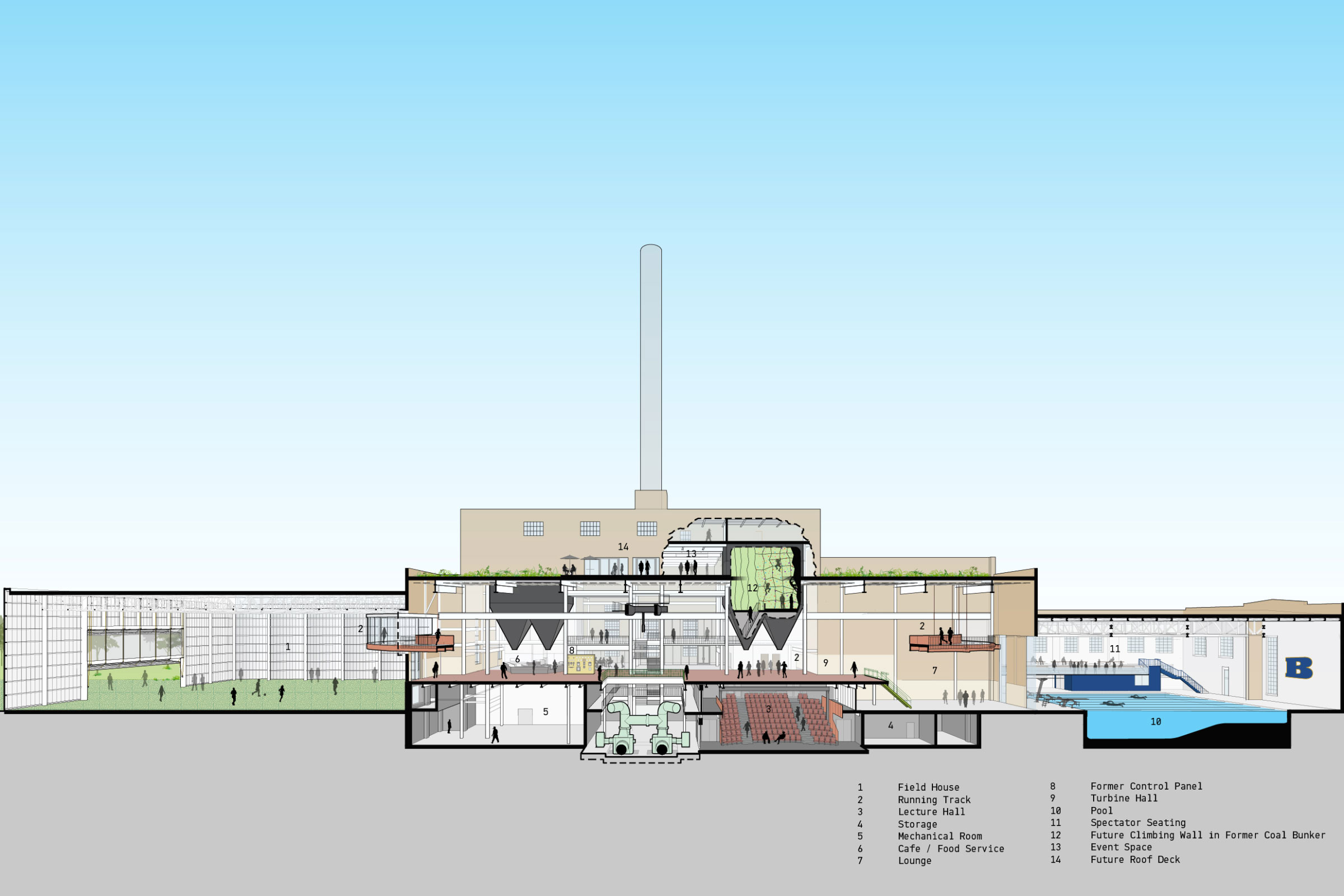

When a college president passed a newly decommissioned power plant, he got an idea: Wouldn’t that space make for a great, much needed new campus fieldhouse? The new facility now has a running track, conference facility, batting cages, café, and more. Photo by Tom Harris

Built between 1907 and 1913, Blackhawk Generating Station—a 120,000-square-foot coal-burning power plant—served the community of Beloit for more than a century before it was decommissioned in 2010 as a result of reduced demand for power. The plant would sit abandoned until, on one of his routine runs around campus, Beloit College’s President Scott Bierman had the idea of converting it into a new rec center.

Designed by Studio Gang, The Powerhouse is the realization of Bierman’s vision. Because of the sheer scale and size of the station itself, the interior layout had to be completely reimagined in order to create a welcoming environment for students. Fortunately, the inherent strength of the structure’s steel frame allowed for innovative design opportunities, such as suspending an entire running track from the ceiling. “It’s using architecture to create that transformation on a spatial level in order to make it this environment you actually want to be in that doesn’t feel too overwhelming or too cold,” Juliane Wolf, partner and design principal at Studio Gang, previously told gb&d.

Diagram courtesy of Studio Gang

Despite these changes to the floor plan, the plant’s industrial history still shines through, with exposed brickwork and steel visible throughout the building. Other features were integrated in more creative ways, including a truss discovered mid-way through the project that now sports a glass facade, creating a sightline between the pool and running track.

The building’s exterior was largely left untouched and the brick cladding left exposed, with the only changes being upgrades to the envelope, new windows, and installation of wall insulations that met the historic preservation standard. Even the plant’s original smokestack was kept and converted into a skylight. Studio Gang also added a 17,000-square-foot field house to the building’s northern face, constructed from translucent polycarbonate walls and steel framing.

8. The Industrialist Hotel, Pittsburgh

The Industrialist Hotel’s historic facade holds rich architectural details, including a Cornice crown with howling masks and a brick and terra-cotta–striped facade on a granite base. The design team completed significant restoration work at the building’s cornice, repairing and replacing structural steel that had been compromised by water infiltration. Photo by Digital Love Studios

In Pittsburgh the Industrialist Hotel is at home inside an 18-story skyscraper built in 1902 and designed by architect Frederick Osterling. The building once served as the headquarters for James Arrott’s American Standard bathtub company.

Because the Arrott Building and several other nearby financial buildings are recognized as contributing property to the National Register’s Fourth Avenue Historic District, it qualified for the Federal Historic Tax Credit program, which helps incentivize owners to rehabilitate historic buildings. This, in addition to the building’s charm and favorable location, influenced HRI Properties and Marriott International’s decision to purchase the skyscraper and convert it into the Industrialist Hotel, the latest location in Marriott’s Autograph Collection.

“The greenest building is the one that already exists,” Kirsten Vaselaar, senior vice president of real estate and development at HRI Properties, told gb&d in a previous article. “By giving the building a new use, bringing it up to code, upgrading all of the building systems, repairing the exterior envelope as needed, and installing a new roof, the project has helped ensure that this building can continue to perform, serve an economic purpose, and contribute to the community for many years to come.”

Stonehill Taylor gave the 124-room hotel its stunning new interior design, blending old and new across three floors of public spaces as well as guestrooms and suites. Historic finishes and features stand out on the first and second floors, as they were preserved and highlighted in the finished project. Photo courtesy of The Industrialist

Retaining the original arched windows, brick and terra-cotta-striped facade, and intricate Cornice crown complete with howling masks, the Industrialist’s exterior is rich in history and architectural detail, setting the stage for what to expect upon entry to the luxury hotel. Stepping inside puts one in the main lobby, left largely untouched and filled with the original Italian marble, brass accents, and intricate plaster work. The only major changes made to the lobby were the addition of new sculptural chandeliers, LED light fixtures, and openings to the adjacent Rebel Room bar/restaurant and bathroom corridor.

The rest of the interior—designed by Desmone Architects and Stonehill Taylor—is noticeably modernized with references to its industrial history throughout. Smoke-like abstract artworks compliment the guest-rooms’ monochromatic color palettes, while each bathroom features dark granite tile juxtaposed against fire-colored wallcoverings and brass fixtures. Avant-garde furnishings and mid-century finishes in the hotel’s ground-floor bar and restaurant, second-floor salon and library, and third-floor event space and fitness center further serve to reinforce the Industrialist’s timeless design and cement its place in Pittsburgh’s industrial past.

9. Black Diamond, Huntington, WV

WXY and Edward Tucker Architects are designing a major adaptive reuse project along with SB Friedman for the community-based group Coalfield Development. Rendering courtesy of WXY architecture + urban design

In 2021 WXY architects + urban design and Edward Tucker Architects were commissioned by Coalfield Development to develop an adaptive reuse plan for a former World War I glider factory in Huntington, West Virginia as part of the region’s efforts to bolster the economy through revitalization of existing brownfield sites and abandoned coal fields. WXY’s proposed strategy will allow the repurposed building—referred to as Black Diamond—to serve two tenants: Solar Holler, a full-service solar panel developer and installer, and ReUse Corridor, a consortium of local collectors, up-cyclers, and material generators.

Constructed primarily from brick and steel, the existing buildings were chosen for their high ceilings and open floor plans, of which can readily accommodate the in-and-out movement of shipment vehicles and blur the line between interior and exterior spaces. Repurposing the existing factory also allows the design team to reuse certain parts of the site in innovative ways.

“We’re able to play with some pieces of gantry cranes and older industrial architecture to make something,” David Vega-Barachowitz, an associate principal at WXY architecture + urban design, told gb&d in a previous interview. “It’s an important message not only for the reuse program that’s on site but also in reflecting back on this economic engine and community center they’re trying to create in this area.” Black Diamond is slated to open in 2026.

10. Two Doughboy Square, Pittsburgh

In the Lawrenceville neighborhood of Pittsburgh, Two Doughboy Square designed by Desmone Architects mixes contemporary and historical design elements. Photo by Ed Massery

In Pittsburgh’s historic Lawrenceville neighborhood, Desmone Architects’ main office—known now as Two Doughboy Square—resides inside the former Pennsylvania National Bank Building, an 8,200-square foot structure originally built in 1902 and designed by the Beezer Brothers architectural firm.

Constructed in the Beaux-Arts style, the one-story brick and terra-cotta bank building was saved from demolition in 1993 when Desmone Architects decided to expand their operations and set up shop in Pittsburgh, selecting the building for its historical significance, optimal location, and impressive arched entryway complete with frieze and ornamental detailing.

Desmone Architects nominated the old bank for City of Pittsburgh Historic Designation, which it received in 2020. Photo by Ed Massery. Photo by Ed Massery

Skilled design and sound construction meant that the bank’s exterior required little alteration, with the only major changes being the replacement of existing windows with energy-efficient alternatives and the addition of a nameplate above the doorway. All of the bank’s original brick and terra-cotta cladding was left exposed and in its weathered state, ranging in color from light brown to taupe. Inside, the bank’s defining features—the high ceilings, arched window cutouts, tall pilasters, and detailed window surrounds—were left intact, though the colors and furnishings were updated for a lighter, more modern feel.

After expanding their main office in 2019—something the Pennsylvania History and Museum Commission thought might detract from the bank’s contribution to Pittsburgh’s historic fabric—Desmone Architects nominated the building for City of Pittsburgh Historic Designation, which would require all changes and alterations be reviewed and approved by the city’s Historic Review Commission. Thanks to the firm’s efforts and the help of Preservation Pittsburgh, the bank received official designation in 2020.

The firm’s WELL Gold-certified 25,000-square-foot addition was constructed behind the main office and sits at a triangular intersection between a residential and commercial district. The south facade faces the residential district and was designed to compliment the bank through its use of Roman bricks and bay windows, whereas the north facade employs a YKK AP curtain wall with black mullions to create a modern look that fits with the commercial buildings it faces.

How to Become a Historic Preservation Architect

To become a historic preservation architect, one must first receive a professional degree in architecture, demonstrate knowledge of American architectural history and the Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for the Treatement of Historic Properties, gain experience through interning or apprenticing at a firm, and finally pass the ARE and apply for architectural licensure. Photo by Ed Massery

Historic preservation is a well-respected architectural practice—one that is always in need of new architects who are passionate about protecting the legacy of historically and culturally significant buildings. Anyone who wishes to become a historic preservation architect will need three things should they hope to turn their passion into a worthwhile career: education, experience, and a valid license to practice architecture.

Education

To become a historic preservation architect, a person must first receive a professional degree in architecture from a school or program accredited by the National Architecture Accrediting Board. Exact degree requirements vary, but many firms prioritize prospective candidates who have completed a Master of Architecture program with a focus on or specialization in historic preservation. Some firms, on the other hand, may accept applicants who have completed a Bachelor of Architecture program, provided they have prior experience in historic preservation.

Prospective historic preservation architects must also need to have a strong understanding of architectural design, building materials, construction techniques, and structural systems, as well as demonstrated knowledge of American architectural history and the Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for the Treatment of Historic Properties. The ability to use computer-aided design software and create detailed drawings and blueprints is also necessary.

Experience

After receiving a relevant degree in architecture, a prospective historic preservation architect must gain practical experience through an internship or apprenticeship program with a firm. Minimum experience requirements—measured in hours—vary from state to state.

Licensing

Finally, anyone who wishes to call themselves an architect—historic preservation or otherwise—will also need to pass an Architect Registration Exam (ARE), as administered by the National Council of Architectural Registration Boards.

After passing the ARE, one must then apply for licensure with their respective state’s Board of Architecture and pass a state-specific exam that showcases knowledge of local zoning laws, environmental regulations, building codes, and permits pertaining to architecture.