Story at a glance:

- A leading architect at Krueck Sexton Partners shares why net zero is no longer enough.

- Incorporating a regenerative design framework allows the design team to explore the best solutions for humans and the natural world across multiple decision points.

- Outdated building codes and zoning laws established in an era of fragmented thinking need to be rebuilt on the grounds of a regenerative design framework.

By 2080 the United Nations estimates that the world population will grow to 10.4 billion people. Correspondingly, we will see a significant increase in buildings to house those people or provide them with a place of employment and services. The scale of this estimated 2.6 trillion square feet in new buildings to accommodate the world’s growing population is comparable to adding another New York City every month for the next 40 years. Even if every one of these buildings was designed to be net zero energy, they would still draw from the electric grid during peak nighttime demand.

We have the opportunity to rethink our design process and ask the necessary questions: Can these buildings generate more energy than they consume? Can the land where we site these buildings be repaired back to the natural ecosystem? What is best for human health and the local communities that occupy these buildings?

A Regenerative Design Framework Approach

A common misconception of sustainability is the idea that nature comes first—and at the expense of human needs or comfort. This mindset of isolating ourselves from nature and doing less needs restructuring so we act as stewards who equally contribute. Historically our best-in-class sustainable design has been focused on doing less harm to the environment, or, at best, reaching zero. Nature is abundant and regenerative; it sustains life. If nature functioned at a net zero model it would not continue to exist. We need to better understand nature’s systems that operate in a net positive way and use that as a guide in our own design process to sustain ourselves, the people who rely on healthy air, water, and nutrients.

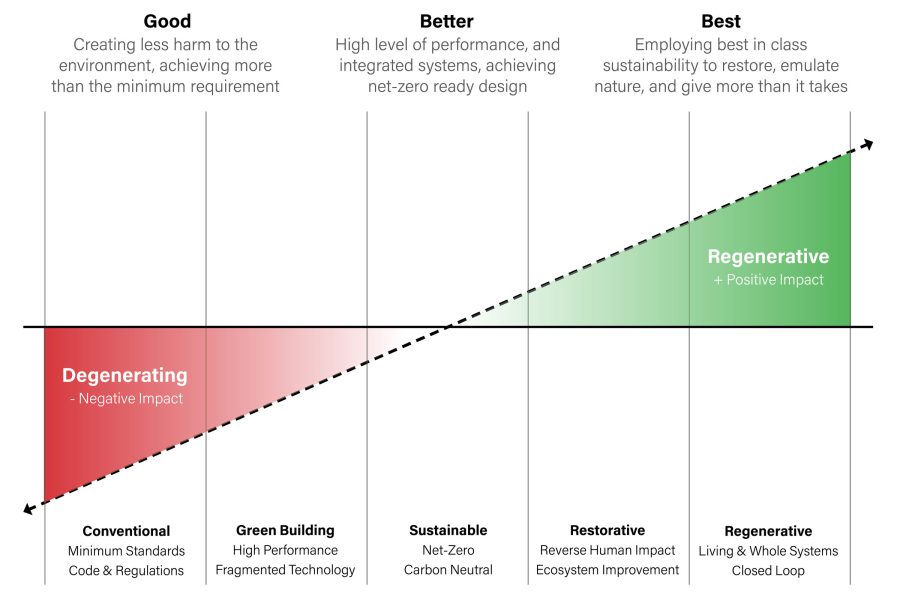

This practice of emulating nature’s genius in design or whole systems thinking is known as regenerative design. The graphic above represents a regenerative design scale similar to the range of sustainability approaches developed by Bill Reed, founding principal at Regenesis Group. The middle of this scale is net zero energy and net zero carbon. As we move past zero or causing no harm to nature, the design solutions become more integrated, emulating what nature is already doing in abundance. Most buildings—even LEED Gold and Platinum—still operate on the left side of this scale, focused on doing less harm.

Setting the Scale Past Zero

Chart courtesy of Krueck Sexton Partners

How do we work with building owners to set a more ambitious project goal? Many large companies and leading institutions have allowed their sustainability targets to remain stagnant. A common goal witnessed across universities, for example, is LEED Silver certification. Today this level of certification is nearly the equivalent to a code minimum building due to updated energy requirements.

This slow pace of code advancements—and continued acceptance of minimum compliance—is not going to position us for a sustainable future. Positively, there are cities, municipalities, and states leading by adopting stretch codes to raise design standards within a “better” category of performance. Convincing building owners to do more than the minimum is not a simple task, but a regenerative design framework opens the conversation to illustrate what design goals beyond net zero can look like.

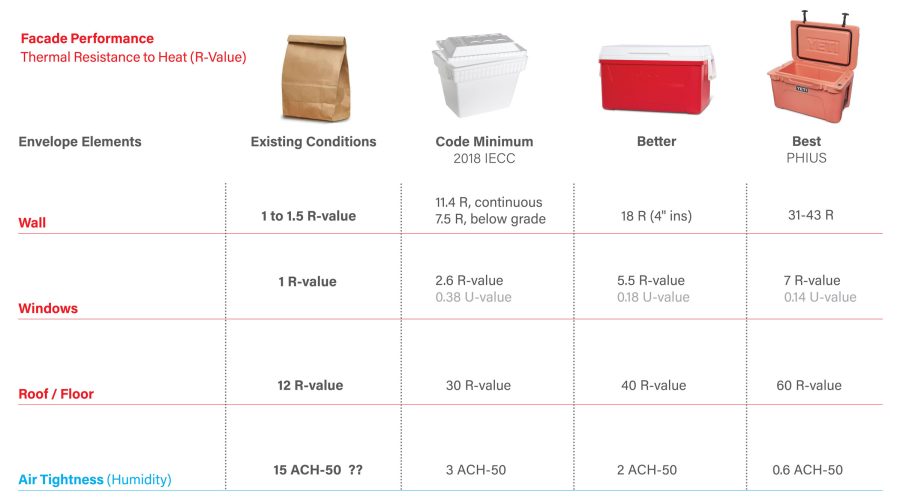

Incorporating a regenerative design framework into the design process allows the holistic design team to explore the best solutions for humans and the natural world across multiple decision points. I find value in representing design approaches with owners in a simplified “good, better, best” method and giving relationship to known things. For example, take a simple project decision like: How much thermal insulation is right for the building’s climate zone? The graph above outlines a decision process with an owner where the “best” category illustrates the required insulation for the building to be a net positive energy producer, or on the regenerative side of the graph. Extend this thinking further by discussing material ingredients of the insulation. A bio-based material that decomposes or recycles easily represents a regenerative material compared to an artificial chemical-based insulation. This process allows us to re-ask those big idea questions from the beginning of the article habitually throughout the decision points of a project.

Regenerative Design in Practice

- Florida Everglades ecosystem. Photo courtesy of Krueck Sexton Partners

- Site before Grogan, existing conditions. Photo courtesy of Krueck Sexton Partners

To understand the best solution or approach to a project with a regenerative framework we typically need a wider perspective. What does nature need to thrive in order to support a healthy ecosystem for us? This was the approach for a 20-acre site in south Florida. Krueck Sexton Partners, the owner, and design team for the Grogan | Dove Federal Building started by asking the right question: What does the site want to be? A clear idea emerged by zooming out to understand how the site fits within a whole system; “Restore the Everglades.” The original site was a paved over vacant lot. Greyfield sites like these often disrupt microclimates with heat islands, requiring costly remediation of contaminated soils, and obstruct hydrology.

After completion of the project, 59% of the site was restored back to its original ecological wetland condition. Wildlife returned with abundant nesting, foraging, and perching available for native species to make home. The project achieved LEED Platinum Core + Shell, Sites certification and is designed to be net zero by 2030.

Yet, when analyzing this project on a regenerative design framework, the building lands in the center of the scale. It is the site restoration story of the project that surpasses net zero into a regenerative level of design by repairing what was previously done. The owner and design team coalesced around an essential element in regenerative design—the importance of connection to place.

After completion of the Grogan | Dove FBI Federal Building, 59% of the site was restored back to its original ecological wetland condition. Photo by Nick Merrick, Hedrich Blessing; courtesy of Krueck Sexton Partners

Image courtesy of Krueck Sexton Partners

Looking Forward

Fortunately, for those of us who will take part in the largest growth of buildings in our world’s history over the next 40 years, we already have every technology and known design strategy available today. We know how to build beyond net zero to repair paved-over sites and restore dilapidated buildings, better connecting us with the natural world.

I often look to resources and leaders like the International Living Future Institute, which has more than 30 certified living buildings as case studies of leading examples in regenerative design. Yet, even these paradigms of regenerative building fall short due to exemptions and regulatory agencies requiring the status quo for construction. In Illinois, for instance, a rainwater cistern to collect water for reuse is not permitted in the plumbing code, requiring special approval. Similarly, a constructed wetland to absorb nutrients and purify our wastewater is not allowed in Chicago.

These building codes and zoning laws that govern our practice were established in an era of fragmented thinking and need to be rebuilt on the grounds of a regenerative design framework. For the building owners, who will step up and ask that we do more than less harm? For the designers, think of each project as an opportunity to challenge code officials and civic leaders, proving we can design as abundantly as nature does. The persistence of integrated teams pushing forward-thinking design solutions will eventually unify enough fragmented parts to comprise a whole.