Story at a glance:

- Converting offices to residential buildings now has federal support, with incentives detailed in a White House Guidebook released in late 2023.

- Some of the features that make office buildings undesirable are seen as luxurious in multifamily housing.

- Architects say the US is 7.5 million homes short. Gensler developed an algorithm to quickly assess the viability for converting office buildings into housing.

Bad offices may be just what the housing market needs. Leaders at Gensler have been studying struggling office properties to understand how some can be converted into housing.

As of March 2024 Gensler has assessed more than 1,300 buildings in more than 125 cities. “It’s a really good mix of different building types, sizes, and locations,” says Steven Paynter, principal and global practice area leader at Gensler based in Toronto.

Gensler’s comprehensive assessment of commercial buildings’ viability for housing has found that some unpleasant office features are actually seen as luxurious amenities in apartment buildings.

Take, for example, the 12-foot floor-to-floor height typical of a Class C building. These are often lowered to 8 feet in the finished office, making the space feel cramped and gloomy after ducts, cabling, and lights are installed. When all of those extras for the office are removed, you can have a soaring ceiling—highly desirable in a residential building, Paynter says.

Conversions: How We Got Here

Gensler transformed an older office asset, the Rivermark Centre South tower in Baton Rouge, into luxury rental apartments. Photo by Ryan Gobuty

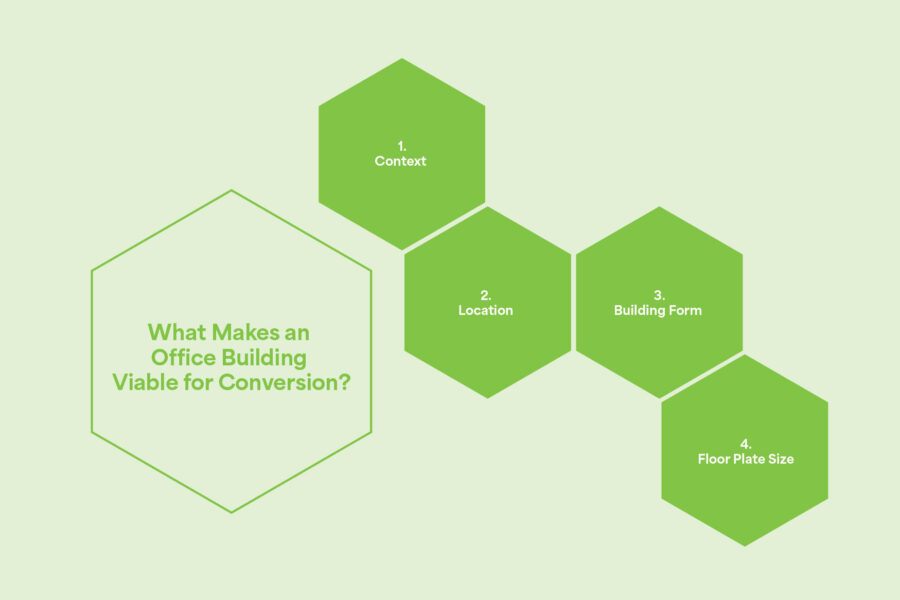

The work to understand conversions began in early 2020, when Paynter and the Gensler team developed an algorithm to quickly assess whether an office building was suited for conversion into housing. What would have taken three or four months they could now do in hours. Context, building form, location, and floor plate size are among the crucial factors in assessing a building’s aptness for conversion. “The process allows you to find the ones that work and the ones that don’t, and then you spend your time on the ones that really do work,” he says.

Before the pandemic Paynter says many in the industry began to worry about a looming recession and its effect on the real estate industry. Gensler started asking clients about their biggest concerns. “We started looking at conversions because our clients were saying they were worried about B and C Class office buildings,” Paynter says. “If you look back through the data, a lot of them have been struggling since 2015. So we started looking at what you would do with those buildings. Do you add amenities? Do you upgrade them or convert them?”

Office markets started to soften in 2015, Paynter says, as many new buildings came online with new top of market amenities. “In some cities this coincided with the drop in energy prices that really decimated downtowns in places like Calgary and Houston, where the market is tied to energy.”

He says the same trend hit other cities later, starting in early 2019 in New York, for example. “It was happening pre-Covid, just not as quickly.”

The idea of converting office to residential was exciting because it worked from a code perspective, a building perspective, and a demand perspective. “Many of the clients we talked to said they’d already spent a substantial amount of money and time studying it, only to find that it didn’t pencil out for them. At the same time we had projects we were doing that were successful that were actually getting built and occupied,” Paynter says.

He says Gensler wanted to understand why sometimes conversion worked, and sometimes it didn’t. What made some buildings successful? “Assuming that all of the clients and all of the designers were as sophisticated as each other, it must be something to do with those existing assets.”

Interest in this research only grew during the pandemic, as people became increasingly invested in working from home and buildings sat vacant. In 2022 prices for those former office buildings began to plummet, and Paynter says incentive programs began to pop up from cities and federal governments to make it attractive to convert those spaces into housing.

What are the Incentives for Converting Office to Residential?

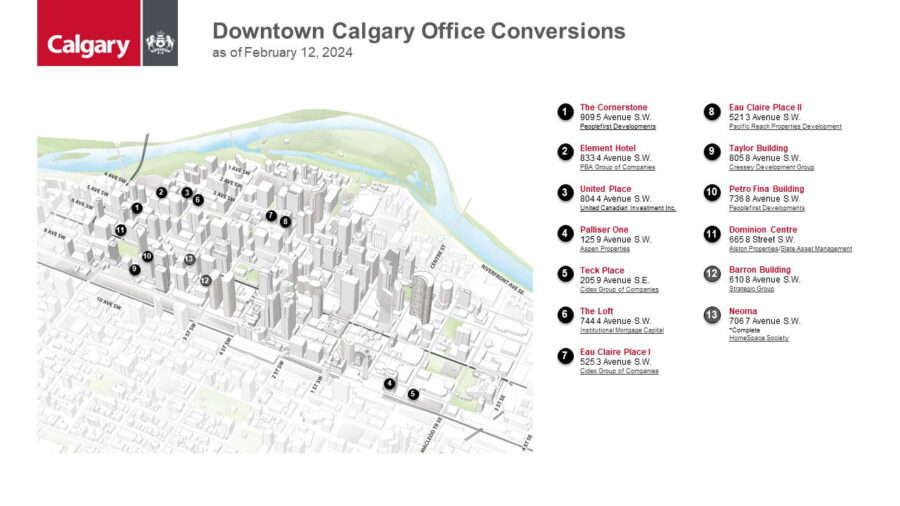

Drawing courtesy of the City of Calgary

Paynter says the need for housing is huge—with 7.5 million homes needed in the US and 3.6 million in Canada as the widely accepted industry numbers, according to Gensler. High interest rates combined with the low inventory are contributing to this issue, as is the growing number of millennials, who are looking for larger homes to raise families, according to the US Government Accountability Office.

In Calgary the oil industry downturn in 2014 ultimately resulted in a downtown vacancy rate of almost 34%, or more than 14 million square feet of empty office space, according to CBRE. The city quickly got to work to implement a simple incentive program for building conversion, and that simplicity is partly why the city is seeing success, Paynter says.

The Canadian city of 1.3 million people has 17 conversions approved as of March 2024 across a mix of office buildings. The 1970s-era buildings would have needed a lot of maintenance to remain office, Paynter says. Converting properties will remove 6 million square feet of vacant office space—a goal Calgary aims to meet by 2031—and provide more than 2,300 new homes possible for Calgarians in downtown.

- The Cornerstone is Calgary’s first completed project from the downtown office conversion incentive program. Photo courtesy of the City of Calgary

- Inside a suite at The Cornerstone in Calgary. Photo courtesy of the City of Calgary

Calgary is providing $2 million in incentives to developers who initiate residential projects in the downtown core to offset any required Plus 15 Fund contribution, up to $1 million per project. Residential development in the downtown core often includes the requirement to contribute to the city’s Plus 15 Fund, which supports construction, operation, and maintenance of downtown’s Plus 15 system (the world’s most extensive pedestrian skywalk system, with 10 miles and 86 bridges connecting 130 buildings). This removes a potential barrier for new residential development as well as any additions to existing buildings to accommodate new residential use, according to the city. Projects must be completed within a designated time period to receive the incentive.

The Cornerstone is the City of Calgary’s first completed building from their residential conversion program. Rendering courtesy of Astra

“Calgary has the best approvals and incentive programs anywhere in North America,” Paynter says. “They didn’t include an affordability requirement at the start, but most of the projects now also include affordable housing or workforce housing—partly because of the incentives and partly because of the market and the lending requirements of Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation. It is allowing them to create these relatively low-cost projects and be super successful.”

White House Guidebook to Conversions in the US

Inside Gensler’s Baton Rouge Rivermark office to residential conversion. Photo by Ryan Gobuty

Cities like Boston and Washington, D.C. also have incentive programs, and more conversions could be on their way, thanks to the recent release of a White House guidebook, directing what Paynter calls serious funds for creating housing.

The guidebook details available federal resources to support commercial to residential conversions through a wide array of federal programs, loans, grants, guarantees, and tax incentives. The Department of Transportation (DOT) is offering new low-cost financing opportunities for conversions and affordable housing that increase housing supply near transportation, and new climate-focused financial resources from the Inflation Reduction Act can make commercial to residential conversions more financially viable while also bringing these buildings to zero emissions.

Some of the programs spelled out in the White House guidebook have been used in conversion projects already; case studies in the guide illustrate how funding from the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) is being combined with Rehabilitation (Historic Preservation) Credits as well as state and local funding to convert and rehabilitate commercial buildings all over the US.

Franklin Tower in Philadelphia, designed by Gensler with PMC Property Group, includes a new two-story rooftop penthouse. Photo by Robert Deitchler

“With the guidebook there are a lot of programs that HUD and other agencies offer that can be used to build new supply or to rehab or convert old supply. Sometimes not all of those potential uses are well known to developers,” says Aaron M. Shroyer, former senior advisor at the Office of Policy Development & Research at HUD. “The goal of the guidebook is to spell out for developers and local governments to create a resource they can turn to explore these different funding sources. Not all sources will work for all projects. Not all might make sense for developers to pursue, but I’m willing to bet that just by virtue of them all being in one place and in a common format that details the program parameters, it’ll be useful for developers to learn more about these resources.”

Shroyer hopes the guidebook educates developers and local governments alike to learn more about these resources. “I think what HUD and the rest of the administration is trying to do is where we have great programs and funds and loans that can be used for conversion, really make that known and make it easier for those funds and loans to be to be used for for conversion for the developers and folks who would like to pursue those pathways.”

Right now he says federal agencies are in the process of hosting various webinars for developers and local governments to go more in-depth, sharing the tools now available. Cities like Memphis and Detroit are already actively looking more at conversions, Shroyer says.

“There’s a lot of work local governments can do to facilitate conversions. For example, sometimes local governments will require that there’s a certain ratio of parking spots for residential development. So there are times when an office building might be right for converting, but the office doesn’t have its own parking, and, by the letter of the local zoning law, to convert the office to housing they would need to find 100 parking spots, which basically makes this private project impossible to make work. Instead, what a local government could do is pass an ordinance that waives requirements for conversion projects.”

Those ones that have been held up by financing, by not being able to get a loan or the loan being too expensive, it should clear that roadblock.

Paynter and colleagues at Gensler worked directly with the White House to develop the guidebook, which included input from architecture, leasing, lending, and Silverstein Properties. “It really solves three things at once,” he says. “It will help to solve the vacancy problem, help to solve the housing crisis, and reusing buildings is the most sustainable way of creating new housing, so it helps with the climate crisis.”

As part of the federal program, the Departments of Energy and Transportation are allowed to lend their current program rates, which is essentially a treasury bond rate plus a small markup, Paynter says. “We’ve heard recently that it’s going to be a treasury bond rate plus .375%—a tiny amount extra. That puts the cost of borrowing somewhere around 4.9 to 5% in early 2024, depending on how long you borrow for. That is probably 60% less than the cost of borrowing for construction right now. That makes a huge difference.”

Paynter and colleagues expect the new federal incentives to be a massive game changer to get projects moving. “Those ones that have been held up by financing, by not being able to get a loan or the loan being too expensive, it should clear that roadblock.”

What Makes an Office Building Worth Converting Into Housing?

Pearl House sky terrace. Rendering courtesy of Williams New York

In their study of more than 1,300 buildings Gensler found that about 30% made physical sense for conversion and were located somewhere people wanted to live. This knowledge can help teams choose buildings more thoughtfully, pursuing projects that actually have a shot, Paynter says.

“Lots of people seem concerned that the number is as low as 30%, but vacancy across the US is only 20%, so that’s good,” he says. “If we can convert even half of those buildings that are a good option then we’ve solved the vacancy crisis that’s happening and made a massive dent in the residential housing. If we hit 15% of the existing building stock, we’d easily create more than a million homes in the US alone. That has a very big impact.”

Context, building form, location, and floor plate size are among the crucial factors in assessing a building’s aptness for conversion.

Gensler’s analysis considered 150 data points for each building, including grading buildings for factors like the viability of their building floor plate and whether it’d be really expensive to change a building’s shape or add a courtyard. When a building was considered to be in a great location, where people would pay a premium to live, that pushed the score up even more. “The major things are really the floor plate and layout. It’s sometimes as simple as a building doesn’t have windows on all sides. A surprising number of offices don’t. You can’t really put residential units if there are no windows,” Paynter says.

If we can convert even half of those buildings that are a good option then we’ve solved the vacancy crisis.

The assessment considered many other factors, too, like does it have the right amount of parking? What about elevators? Are the exit stairs conveniently located? “We’re really able to answer, ’Is this going to work, or is it just going to be really expensive?” Paynter says. “You see a lot of projects where people start with the wrong building, and they’re like, ’Oh, it’s too expensive to do this.’ If you start in the wrong building, it’s definitely prohibitively expensive. Find the right one, and it’s great.”

Not all cities are created equally; some, like New York City, have high residential value. Gensler is currently working on a Lower Manhattan project, 160 Water Street (Pearl House). The building required significant work to convert it, but Paynter says that’s OK because the value in that area is high. “In cities like New York, Boston, or Toronto it’s super viable to do these projects.”

Areas with poor office markets or places considered single industry cities, like Detroit, are also viable for conversion, according to Paynter, who points to the vacancies left when car manufacturing widely disappeared from the Motor City.

Conversion in Action: NYC

The team behind 55 Broad Street said the building’s design allowed for essentially two floors to be added on the roof. Rendering courtesy of CetraRuddy Architects

Developers say 55 Broad Street—a 420,000-square-foot Class B office building in NYC that was built in the ’60s—is destined to be a commercial to residential success. The building in the Financial District is a dream conversation, according to David Marks, head of acquisitions for Silverstein Properties, the developer of the project. The location, the floor plate, the condition of the windows, the column spacing, the ceiling height, natural light, and the ability to convert mechanical floors to residential space—these are just some of the features he says make the CetraRuddy-designed project worthy.

“The mechanical program we designated for the building allowed us to eliminate 95% of the building-wide mechanical systems. We gained a lot of square footage from those mechanical spaces,” Marks says. When all is said and done 55 Broad Street will be an all-electric, zero emission, carbon neutral building.

Overall the project required no “structural acrobatics,” like drilling light wells through the building, like Marks has seen in other projects and considers a drawback. “We didn’t need to reskin the building. We were just replacing the existing windows with new windows, which was a great feature. We could remap the mechanical deductions and add essentially two floors on the roof. We’re adding one floor within the parapet wall, and then we’re adding a steel structure floor on top of that floor. So we’re really adding six floors to an existing 30-story building.”

The building also has 14-foot ceilings in the basement, which allowed the team to house most of the amenities in the basement without compromising any residential square footage within the vertical density for the amenities. “It’s super-efficient in that sense,” Marks says.

Four of the 10 elevators will become trash chutes or more residential space. “Again, that allows us to squeeze a bit more efficiency out of the building.”

A residential unit inside 55 Broad Street. The building is expected to open to residential tenants in 2025 and will pursue LEED. Rendering courtesy of CetraRuddy Architects

Marks says the project, now under construction with first move-ins anticipated in January 2025, is unique, and he would know; he and his team have considered many conversion candidates. “In this market, because of interest rates and cap rates, things are a bit more challenging now, but we are continuing to look for similar opportunities in New York and other markets.”

That said, it won’t be easy to find another building like this, he says. “I don’t think this will be easy to replicate, with the physical features of the building configuration and the site plan. Those are all great features in one building. I’m sure there are others out there, but not many.”

Still, Marks says major metropolitan areas like New York are oversupplied with Class B and under-supplied on residential. He says the cost to convert can deter developers, but if the floor plates can be converted to residential and you can establish more rental square footage as a result as compared to other buildings, that’s a plus.

“If you need to start cutting through the building or creating blind shafts or setbacks, those all cost a lot of money if you need to add a lot of square footage vertically. If you can do that without bracing, great.”

The Challenges of Conversion

A coworking space as imagined inside the 55 Broad Street office to residential conversion project in New York City. Rendering courtesy of CetraRuddy Architects

Paynter says the next step is to work out the application process for federal funding and help departments that aren’t used to working with housing—the Department of Transit and the Department of Energy. “They don’t build housing supply. So we’re working through that process with them now to try to streamline it to get the money flowing,” he says. “It’s been very positive.”

DOT released guidance to states, localities, and developers on how the Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act and Railroad Rehabilitation & Improvement Financing programs—which combined have more than $35 billion in available lending capacity for transit-oriented development projects at below market interest rates—can be used to finance housing development near transportation, including conversion projects.

HUD also released an updated notice on how the Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) fund, $10 billion of which has been allocated during this Administration, can be used to boost housing supply—including the acquisition, rehabilitation, and conversion of commercial properties to residential uses and mixed-use development.

HUD is also increasing outreach efforts to support municipalities and developers seeking to use HUD tools to finance conversions. States and localities can access up to five times their annual CDBG allocation in low-cost loan guarantees to fund projects such as the conversion of properties to housing or mixed-use development. In addition, HUD will make awards through a research-related Notice of Funding Opportunity, which can be used to develop case studies that can serve as roadmaps for other localities interested in pursuing conversions.

Gensler has completed four conversion projects in North America and 35 more are ready for city approvals; 120 are in early stages.

Still, cost versus value can make it difficult to make projects happen, and approval timelines are a nightmare, Paynter says. “If I’m a developer, and I borrow money to buy a site or a building and I have to sit and wait two years for approvals, which is pretty common in a lot of cities, I’m paying interest for two years. Pre-Covid that didn’t really matter; it was half a percent. Now it’s five-and-a-half, six, or higher. I’m wasting that money for two years paying interest on a large loan to buy the site or the building. No one benefits from that. It just disappears that money, and it gets put onto the price of rent or the price of the condo at the end of the day,” he says. “It’s not like when you spend more money on construction and people benefit from it. It’s just spending more money and wasting time. Cities need to take that more seriously and get the approval timelines down to something much more reasonable.”

Gensler has completed four conversion projects in North America and 35 more are ready for city approvals; 120 are in early stages. “The main thing preventing more being completed is the tight construction lending market,” Paynter says.

Rising interest rates that remain high make construction projects more difficult to pencil. “A lot of cities are still burying their heads in the sand to some degree and still putting development charges up and land tax up, which just makes it almost impossible to make any of this stuff happen,” Paynter says.

The Benefits of Conversion

The rooftop floor at 55 Broad Street will open up to beautiful views and a pool. Rendering courtesy of CetraRuddy Architects

Beyond meeting a need for housing and filling sometimes depressing, vacant buildings, converting an underutilized office building into residential is good for the environment. You’re not tearing down, rebuilding, or building something new elsewhere, you’re adaptive and also reviving the community and any suffering economy surrounding it.

“There are social aspects of it,” says Marks, pointing to 55 Broad Street. “Half-vacant office buildings mean foot traffic in the immediate area is significantly down. That affects retail and overall economic activity in the neighborhood. Small businesses are shutting down because there isn’t enough foot traffic and activity.”

He says no one likes vacant retail storefronts, and vacant, dark retail storefronts bring homelessness and an overall lower sense of safety in communities. “It affects the city’s income tax and real estate taxes.”

Turnstile data when Silverstein closed on 55 Broad Street showed less than 200 people entering the building every day. “Replacing this with 571 apartments is expected to house over 1,100 residents in the building,” Marks says. “That’s 1,100 residents that most likely work in New York City, earn a decent income, and are going to spend it in the immediate vicinity.”

The effects will be felt very quickly for some—from an expected increase in NYC Transit ridership to more people spending money at local restaurants and bars as well as utilizing services like the dry cleaners and stores. “That’s a huge social aspect, and it brings safety. It brings life to the neighborhoods in the area.”

That’s double what the building currently generates.

The current building generates roughly $3.5 million in real estate taxes today and is expected to stabilize in approximately eight years at north of $10 million, when the transitional phase is over and real estate taxes are fully phased in, Marks says. “That’s double what the building currently generates,” he says. “You did good by the environment, you did good by the community, and you did good by the municipality. We and Metroloft as the developers created tremendous value because this office building in today’s market would probably trade in the mid $100 millions. When we are done this residential building we think will be somewhere in the mid 500 millions. By creating all that value I think we’re doing good, not only financially, but we’re doing good as a responsible developers.”

The location, he says, speaks for itself. “It’s very tough for tenants in New York City at the moment. Since (partial tax exemption for new multiple dwellings) 421-a expired the inventory has dried up dramatically.” He says continued demand is fueling a rise in city rents, breaking records month after month.

“You bring the inventory, you somewhat help that problem. Tenants in the Financial District are predominantly young professionals, young families, and couples. These are people who want to live south of 23rd Street. If you take a building like 55 Broad, with the amenities, the finishes, the experience, and the management, if you take the exact same product and put it in the desired neighborhoods of the West Village or SoHo or Greenwich Village, the rents in those neighborhoods will probably be, I’d conservatively say 20% higher. You’re really offering tenants a value proposition to live within a 15-minute city bike ride or a walkable distance to SoHo and West Village and all those desired neighborhoods, and you’re paying 20 to 25% less. Those value proposition alternatives are necessary in such a supply constrained market.”