Story at a glance:

- Universal design aims to create spaces that are usable by all people without the aid of specialized designs or adaptations.

- Universal design is governed by seven core principles: equitable use, flexible use, simple/intuitive use, perceptible information, tolerance for error, low physical effort, and size/space for approach and use.

- Curb cuts, ramps, automatic doors, and curbless showers are a few common examples of universal design solutions.

More than 1 in 4 adults in the US has some type of disability, and it’s never been more apparent that everyone has their own needs and abilities that will change throughout their lives.

Universal design principles can and should be implemented in everything we design in an attempt to accommodate as wide a demographic as possible.

This article provides an introductory overview of universal design and its principles, including a few examples of universal design in the built environment.

What is Universal Design?

Architect Ronald Mace is known for coining the term universal design in 1985 as well as for his work advocating for people with disabilities.

Mace originally defined universal design as “design that’s usable by all people, to the greatest extent possible, without the need for adaptation or specialized design.” This definition is still used by the Center for Universal Design today.

True universal design is constantly evolving in response to advancements in our own understanding of the diversity of human experiences. This sentiment is expressed in Jordana L. Maisel and Molly Ranahan’s Beyond Accessibility to Universal Design, in which they write that “universal Design should therefore be considered a process rather than an end state. There is never any end to the quest for improved usability, health or social participation.”

In the years following its introduction universal design has been embraced throughout the industry. This can be seen at trade associations like the National Association of Home Builders, which offers a variety of accessibility certifications, as well as at newer organizations like the Living in Place Institute, a professional education leader that helps people design and build homes where they can safely, comfortably, and independently age in place.

Universal Design vs Accessible Design vs Inclusive Design

Universal design is often used interchangeably with accessible design and inclusive design, though all three terms are unique in their own way:

- Accessible design is concerned exclusively with making buildings, interfaces, and other technologies usable to people with disabilities (including physical, visual, auditory, and cognitive disabilities); accessible design has a narrower scope than inclusive design as it is focused on ensuring specific accommodations are met.

- Inclusive design looks to create products, services, and environments that understand and enable people of all demographic backgrounds and abilities; rather than take a one-size-fits-all approach, inclusive design recognizes that one-size-fits-one solutions are often necessary.

- Universal design aims to create a single design solution that may be accessed and used by as many people as possible, without need for adaptations or specialized design strategies; universal design has its origins in architecture and is best suited to buildings and other tangible or environmental contexts.

All three types of design can, and often do, overlap—especially when it comes to inclusive and universal design in the built environment. From a technical standpoint, each type of design should be regarded as fundamentally separate from the others.

The 7 Principles of Universal Design

Universal design is defined by seven principles: equitable use, flexible use, simple and intuitive use, perceptible information, tolerance for error, low physical effort, and size/space for approach and use. Photo courtesy of Excel Dryer

In 1997 the Center for Universal Design at North Carolina State University identified seven core principles as being foundational to successful universal design: equitable use, flexibility in use, simple and intuitive use, perceptible information, tolerance for error, low physical effort, and size and space for approach and use.

1. Equitable Use

Universal design should be both useful and marketable to people with diverse abilities in a way that does not stigmatize or segregate users. An emphasis is placed on providing all users with an identical experience whenever possible and an equivalent one if necessary, which in turn helps ensure the experience remains appealing to all users.

2. Flexibility in Use

Successful universal design is capable of accommodating a wide range of individual abilities and preferences—that is, it provides flexibility of use. In practice this means providing users with choices in the method of use, adaptability to the user’s pace, accommodations for both left- and right-handed access/use, and features that ensure user precision and accuracy.

3. Simple & Intuitive Use

If a design cannot be understood by everyone who uses it, it isn’t universally accommodating. That’s why successful universal design solutions are characterized by their relative simplicity and ease of understanding, qualities that facilitate intuitive use regardless of the user’s knowledge, experience, language skills, or concentration level. This typically involves arranging information by importance, providing effective prompting/feedback during and after tasks, and remaining consistent in user expectations across language and literacy levels.

4. Perceptible Information

In the same vein, it’s important to ensure all necessary information associated with a design is effectively communicated to the user, regardless of their own sensory abilities. Perceptible information may be achieved by maximizing legibility and through the use of multiple different modes (e.g. verbal, tactile, pictorial) for redundant expression of crucial information. To further facilitate simplicity of use and perception—especially in the built environment—it can also be beneficial to clearly differentiate certain elements so as to make giving and following directions easy for any user.

5. Tolerance for Error

As perhaps the most important principle, tolerance for error refers to a design’s ability to minimize hazards and any adverse consequences of unintended or accidental actions. This often looks like providing legible and easily understood warnings of errors and hazards, inclusion of fail safe features, discouraging unconscious actions in tasks that require focus and vigilance, and taking measures to ensure that all hazards are shielded, isolated, or eliminated altogether.

6. Low Physical Effort

Something that has been designed for universal use may be used efficiently, effectively, and comfortably without requiring strenuous effort on the user’s part, regardless of their physical ability. This typically means ensuring the design only requires reasonable force to operate and allows the user to maintain a neutral body while at the same time minimizing the need for repetitive actions and sustained physical effort.

7. Size & Space for Approach & Use

Lastly, universal design provides appropriate size and space for approach, reach, manipulation, and general use regardless of the user’s posture, mobility, ability, or body size. When put into practice, this looks like designing spaces that can easily accommodate wheelchairs and other assistive devices, accommodating variations in hand/grip size, providing clear lines of sight to all important components for standing or seated users, and ensuring those components may be reached when standing or sitting.

The 8 Goals of Universal Design

There are 8 goals associated with successful universal design: body fit, comfort, awareness, understanding, wellness, social integration, personalization, and cultural appropriateness. Photo courtesy of Oatey

In an effort to build upon and clarify these principles, Edward Steinfeld and Jordana Maisel developed the eight goals of universal design in their 2012 book, Universal Design: Creating Inclusive Environments.

These eight goals of universal design are as follows:

- Body fit. Accommodates a diversity of body sizes and abilities.

- Comfort. Any and all demands associated with the design are kept within the desirable limits of bodily function.

- Awareness. All critical information associated with the design’s use is easily perceived.

- Understanding. The use, operation, or manipulation of the design is clear, intuitive, and unambiguous.

- Wellness. The design contributes to the promotion of health, prevention of injury, and avoidance of diseases.

- Social integration. All groups that use the design are treated with respect and dignity.

- Personalization. Opportunities for choice and personal preferences are incorporated into the design.

- Cultural appropriateness. The design reinforces and respects cultural values and the environmental, social, and economic context of the project as a whole.

There is considerable overlap between the goals and principles of universal design, with the goals serving primarily to update the principles by incorporating considerations for social participation, human performance, and health and wellness.

3 Examples of Universal Design in the Built Environment

Now that we’ve a better undersstanding of what universal design is, let’s take a look at a few product examples of how universal design may be implemented in the built environment.

Ramps & Curb Cuts

Industry professionals are increasingly turning to aluminum, as they love the reusable, cost-effective nature of EZ-ACCESS ramps. Photo courtesy of EZ-ACCESS

As the quintessential example of universal design, ramps—and by extension, curb cuts—have long served as remedies to the inherent limitations posed by stairs in the built environment. Ramps are also one of the most common examples of accessible design, with the ADA requiring ramps and curb ramps be installed along all accessible routes spanning level changes greater than half-inch.

EZ-ACCESS is a leading provider of ramps and other access solutions for commercial, industrial, residential, and recreational spaces. EZ-ACCESS’ PATHWAY HD Code Compliant Modular Access System meets all ADA requirements as well as IBC, OSHA, and most local code guidelines. PATHWAY HD is constructed from high-quality corrosion-resistant aluminum and features slip-resistant Gecko Grip raised-rib tread to ensure safe use in all weather conditions.

“EZ-ACCESS Modular Access Systems have a permanent, slip-resistant surface and smooth, continuous handrails for safe traversing in all weather conditions,” Mike Johnson, national vice president of commercial and industrial sales at EZ-ACCESS, previously wrote for gb&d. “They provide maximum stability by utilizing their own base rather than being buried into the ground.”

And while wheelchair users are often cited as the main beneficiaries of ramps and curb cuts, those using walkers, canes, crutches, and other permanent/temporary mobility aids benefit as well, as does anyone maneuvering a stroller, hand trolley, or other wheeled device—or anyone who’s ever tripped over a step, for that matter.

Curbless Showers

QuickDrain ShowerLine linear shower drain is seen here in a beautiful curbless shower. Photo courtesy of Oatey

As the name suggests, curbless showers lack the raised threshold emblematic of traditional shower/tub systems, thereby eliminating the physical barrier that so often inhibits accessibility. Curbless walk-in showers are accommodating of wheelchairs and other mobility devices while also reducing the risk of falls in what is oftentimes a slippery space.

Another benefit of curbless showers is their support of linear drain systems. Conventional center-point shower drains require a four-directional slope that can be challenging to navigate for those with mobility issues, but linear drains are unobtrusive and only require a one-directional slope towards the drain.

“Linear drains are the ideal design solution for creating ADA-compliant showers and universally accessible wet spaces,” Marlee Gannon, director of wholesale product and channel at Oatey Co., previously wrote for gb&dPRO. “With no barrier to cross, the floor more easily accommodates a freestanding bench, wheelchair, or other mobility aids.” Oatey is a leading provider of high quality plumbing products and owns the QuickDrain brand.

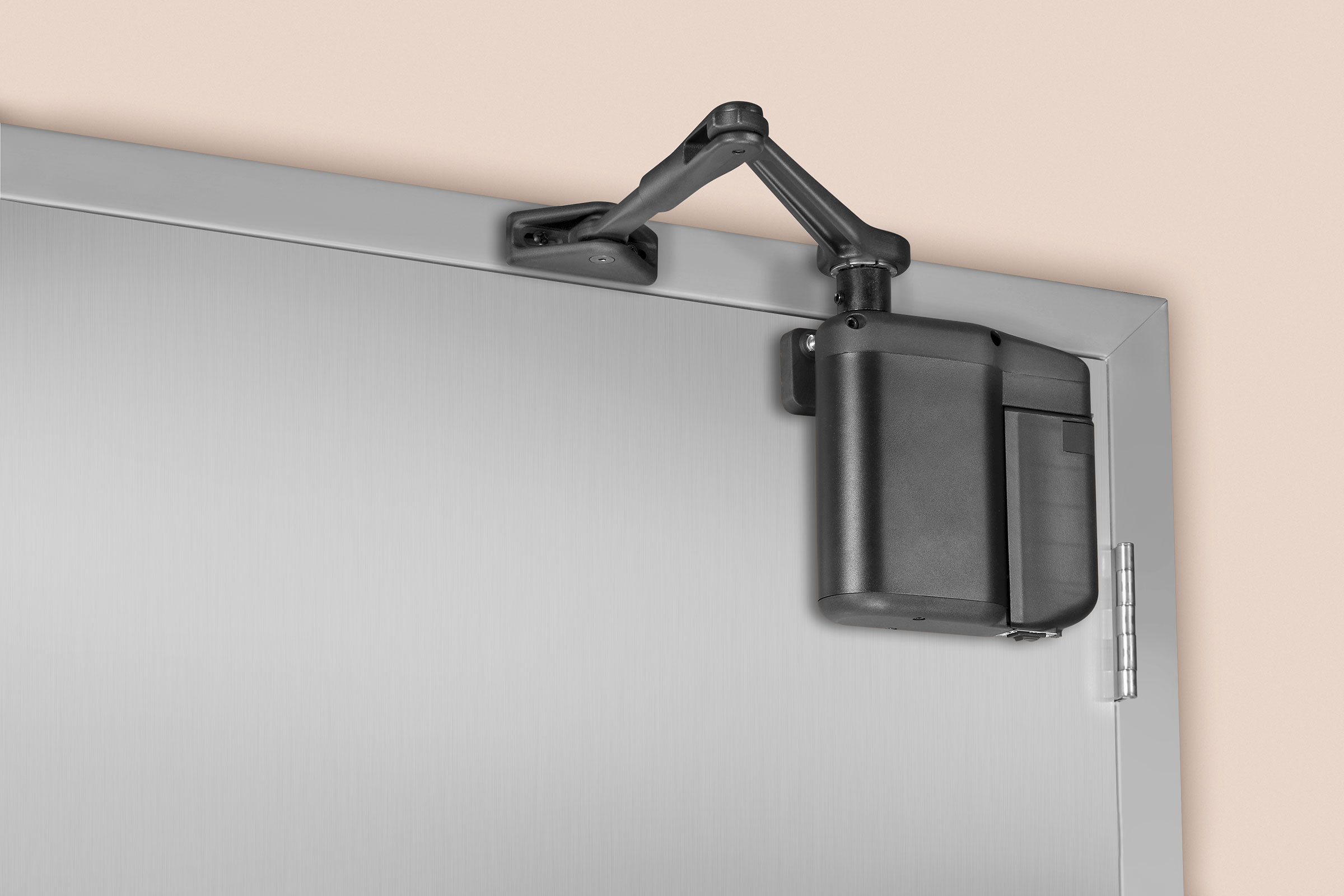

Automatic Doors & Door Operators

Push side mounting with electrical power. Photo courtesy of ASSA ABLOY.

After stairs, traditional pull-handle and turn-knob doors are the second-most common barriers to achieving universal access in the built environment. Not only do these pose an inconvenience to persons with wheelchairs, walkers, and other mobility devices, but also people with strollers or hand trucks, individuals who are carrying something in both hands, persons with limited mobility in their hands/wrists/arms, et cetera.

In recent years many of these doors—at least in public spaces—have been replaced with automatic sliding doors that open when their sensors detect movement, greatly improving overall accessibility and ease of building use.

Of course, it isn’t feasible, possible, or practical to replace every single door with automatic sliding doors, especially when it comes to retrofits, renovations, and preservation projects—or even most residential projects, for that matter. In these instances it often makes more sense to install an automatic door operator, a device that opens a swing-door at the press of a push-plate, holds it, and then closes it after a set amount of time has passed.

ASSA ABLOY is a global leader in both mechanical and digital access solutions, including low-energy automatic door operators like the 5800 Series ADAEZ model. Designed to be easily installed on most types of swing-doors, the ADAEZ supports both push- and pull-side mounting and features a regenerative drive battery that captures power created by manual operation of the door (though the company does offer models that can be plugged into a wall transformer).

“When a person arrives at the door and requires the use of a push-button to open it automatically, the required electricity comes from that onboard battery instead of from the grid,” ASSA ABLOY’s Amy Musanti told gb&d in a previous article. “That push button can either be wired or, for even easier installation, triggered by radio frequency.”

In keeping with the philosophy of universal access, ASSA ABLOY intentionally designed the ADAEZ to be an affordable solution “Many of the customers who need this type of solution don’t have the most generous budgets,” writes Musanti. “We need to get away from this idea that a responsible building should cost more. The ADAEZ is meant to be an accessible and sustainable solution.”