Story at a glance:

- Completed in 2020, Schoonschip Amsterdam is a self-sustaining floating neighborhood with 100-plus residents.

- The circular and sustainable community features 500 solar panels, 30 heat pumps, and water treatment technologies.

- As an urban ecosystem embedded within the fabric of Amsterdam, Schoonschip creates a new model for circular and resilient city design.

In 2008 TV Director Marjan de Blok had an ambitious idea: Build a sustainable floating neighborhood. After filming a documentary about a floating home, she fell in love with the concept of living on water and wanted to push the boundaries of traditional houseboats and resilient city design. She reached out to a few friends and the project was born, but the idea quickly outgrew its smaller roots.

“The project grew and grew and the sustainable possibilities developed, so we just grew along and here we are with 46 households living in this sustainable neighborhood, inspiring people worldwide,” de Blok says.

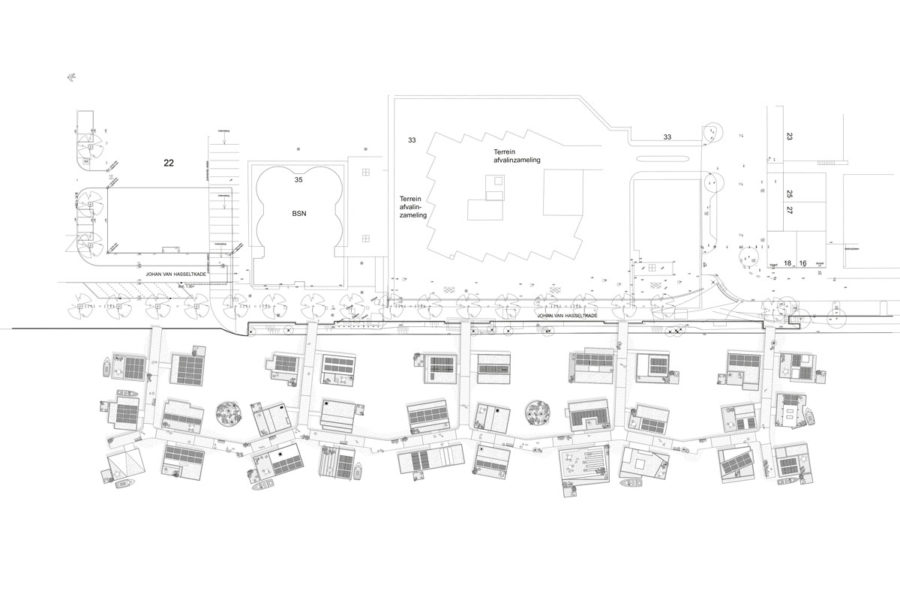

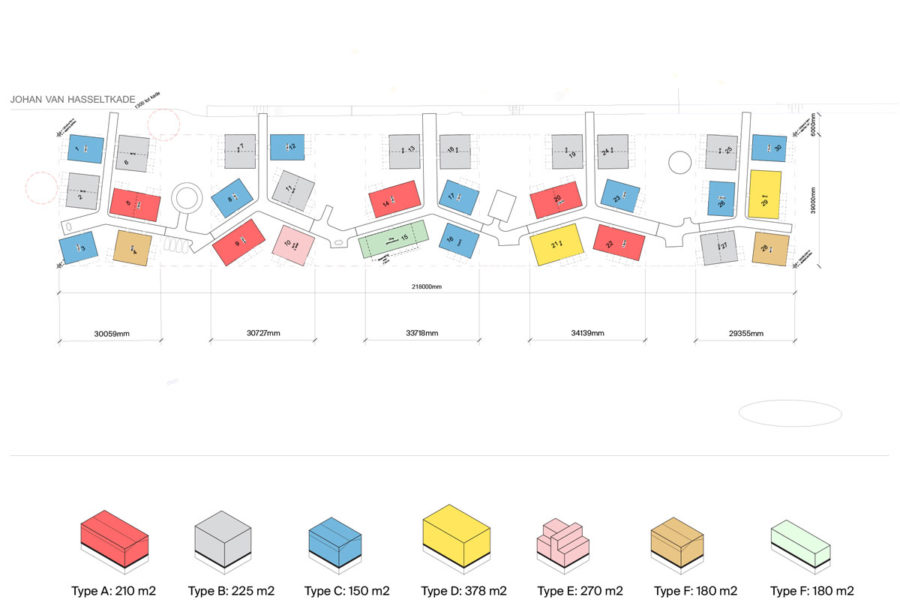

Completed in 2020, Schoonschip Amsterdam is a circular and self-sustaining floating neighborhood in Buiksloterham, a rapidly growing area with a strong industrial past in Amsterdam-Noord. Over 100 people live on 30 water plots on the Johan van Hasselt Canal. Half of the plots are divided into two households to increase accessibility, amounting to 46 homes in total.

Schoonschip functions as an urban ecosystem with shared services like mobility, energy, water, and waste. As sea levels rise and cities search for new housing accommodations, this sustainable floating community provides an innovative solution to global climate change.

“Schoonschip is transformed into thriving neighborhoods based on regenerating existing nature and ensuring social, ecological, and financial value remains with the community. This ensures a network of stewardship and care, which will keep the neighborhoods operating in a circular way for perpetuity,” says Sascha Glasl, cofounder of architectural firm Space&Matter.

Initiated and developed by the residents themselves, Schoonschip reimagines how sustainable cities are designed—and who designs them.

Sustainable Building Materials

A resident commissioned i29 Architects to design this modern and angular three-story home with eco-friendly materials. Photo by Ewout Huibers, courtesy of i29 Architects

From wood cladding to modern asymmetric roofs, Schoonschip’s floating homes feature a wide variety of architectural styles and creative finishings. To minimize the project’s environmental impact, the residents strived to use natural resources that fit within a circular economy. They commissioned Space&Matter to develop the project’s urban plan and building envelope, and each resident worked with an architect of their choice to design their home.

Many of the residents chose to construct their homes with timber and FSC-certified wood. Bio-composite materials—such as wood fiber, burlap, or in one particular home, straw—were commonly used for insulation.

Circular Ecosystem and Energy Efficiency

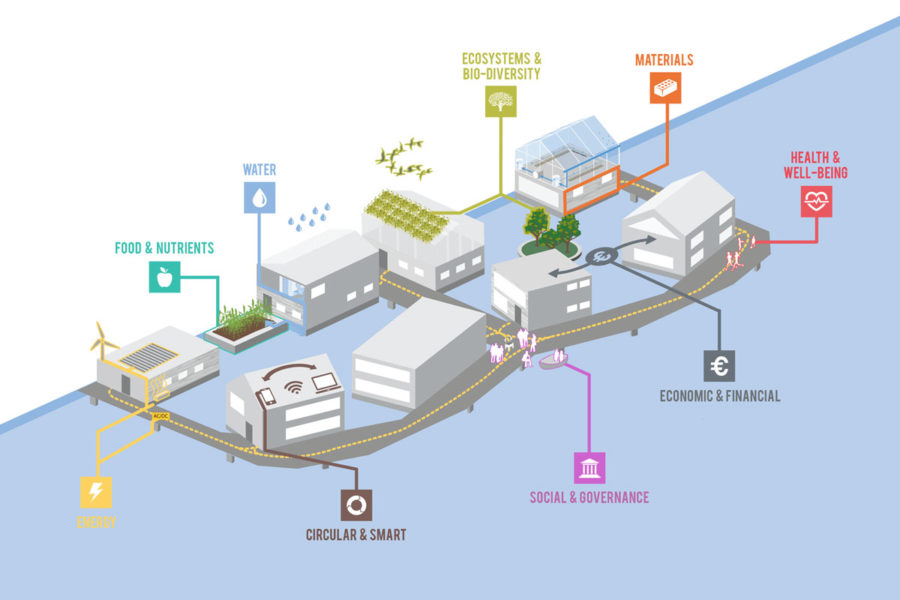

In partnership with Space&Matter, Metabolic developed a cutting-edge sustainability plan for the floating neighborhood. Courtesy of Metabolic

Designing to create a circular ecosystem was among the project’s biggest challenges. Metabolic helped to draw up the project’s sustainability plan, and Grid-Friends and Spectral Utilities developed an advanced smart grid to connect all the homes to one municipal electricity grid. Using 500 solar panels and blockchain technology, Schoonschip residences can produce electricity and exchange energy among households.

Yvonne van Sark, a Schoonschip resident and chair of the community board, says the neighborhood essentially creates its own energy cooperative. “If I’m at home and I generate electricity, and my neighbor is putting on the washing machine and doesn’t have electricity at the time, it’s all interconnected in a smart grid,” she says.

Each household includes a green roof, covering at least one-third of the roof area, where residents can grow food and plants. When combined with the solar panels, the green roofs provide natural cooling and increase the panels’ efficiency.

Schoonschip also uses innovative water treatment technologies to recollect energy and nutrients from wastewater. The wastewater is separated into two categories: “gray water” for kitchen drainage, shower, washing machines, and dishwashers and “black water” for human waste. Through a pilot program with regional water supplier Waternet, the black water will be fermented and converted into energy at a biorefinery.

The neighborhood’s tap water is heated with solar boilers and heat pumps, and many residents installed water-efficient showers to recirculate water through a closed circuit. These showers save nearly 90% of water and reduce energy consumption by approximately 80%, according to Schoonschip.

Dual-Purpose Jetty

The jetty creates a social meeting space for residents, while also supplying the community’s energy, water, and waste systems underneath. Photo by Isabel Nabuurs

On the surface, a jetty creates a social pathway and meeting space for residents. The jetty connects the dwellings like a highway then separates into “streets” of around six houses to form an even smaller, close-knit community.

For the jetty’s social components, the inhabitants asked Space&Matter to create a space where people can easily interact and children can meet and play, says Space&Matter’s PR and Communications Manager Justine Kontou. Over the past year residents have decorated the jetty with plants, greenery, and floating gardens to form a welcoming and vibrant environment.

Underneath the surface, a functional and sustainable connector attaches the energy, waste, and water lines to each household. In essence, the jetty forms the basis for Schoonschip’s smart energy grid.

“The main idea is that instead of all arranging as a household, your own connections to the water, energy, waste streams, it’s important to start acting as a neighborhood and doing it all together,” Kontou says. “That’s really simple, but in the end that’s also the most important thing.”

The jetty’s infrastructure can be replicated in towers, buildings, or streets, Kontou says, which can provide a model for future smart and resilient city design.

Social Sustainability

- The jetty provides a common space for kids to meet and play. Photo by Alan Jensen

- In the summer, everyone is swimming and playing kids rule the jetty, de Blok says. Photo by Alan Jensen

Schoonschip is not only sustainable in an ecological sense, but socially, too: The residents work together to realize the plans for the neighborhood and area. Aligning with the city of Amsterdam’s ambition to reduce vehicle usage, Schoonschip residents formed a shared mobility hub with electric cars and scooters.

After the neighborhood board viewed several presentations on mobility startups, they chose a company they felt suited their community best. Now the residents use an app to reserve an electric car from the shared parking lot, and neighbors outside of Schoonschip are joining in on it, too.

“Now they are also in connection with some of the neighbors who are living all around and also want to integrate into the mobility hub, so it’s getting bigger and bigger,” Kontou says. “They are inspiring the other new neighbors in the area and they are copying the same behavior.”

Simply by looking around, one can see the neighborhood’s ample social sustainability efforts. Floating gardens decorate the jetty, amplifying wildlife and adding color to the neighborhood. A resident suggested making compost, so a batch of land was designated for it. Through working groups—where community members meet and discuss future projects—residents transform their ideas into actionable solutions to improve the neighborhood and the environment, van Sark says.

Some of these working groups align with sustainability, such as the gardens, mobility hubs, or compost, but some are simply for fun. People can create groups for knitting or handwork, and one of the houses features a clubhouse where residents can eat and spend time together. The clubhouse currently isn’t usable due to COVID-19, but that hasn’t stopped the Schoonschip residents from finding creative ways to foster community.

To celebrate Valentine’s Day, 10 households split into groups of five to deliver dinner to each other’s homes. Last fall, when a neighbor messaged their WhatsApp group to share that a friend’s restaurant was struggling, the community pitched in on an order together. Since many people are isolated due to the pandemic, it’s small things like this that really make a difference, van Sark says.

The Future of Resilient City Design

As an urban ecosystem embedded within the city, Schoonschip Amsterdam provides a new model for sustainable living and resilient city design. Photo by Alan Jensen

Developing this circular, sustainable, and social community is the first step, but transforming the future of resilient city design is next. Social sustainability is also about access to information, van Sark says, and the Schoonschip residents hope to spread this knowledge beyond their close-knit community.

“The residents of Schoonschip feel responsible to share all their learnings and all the knowledge they collected in the last years with everyone to stimulate this kind of circular neighborhoods in Holland but also abroad,” Kontou says. Community members meet with a variety of professionals, scientists, and architects to share their perspectives as inhabitants. They are also participating in a European research project and founded a nonprofit to cooperate with more partners.

Kontou credits some of this drive to the foundation of the project itself. Since de Blok and the residents initiated and developed the project, many of the inhabitants feel strongly connected to the neighborhood and what it stands for. By centering future residents in what Kontou calls a “bottom-up” participatory process, people will feel more connected to their communities.

“We believe that this kind of looking at city- and neighborhood-making can really make a difference, because from the beginning you get to learn your neighbors together. You’re involved in creating ideas and then co-creating your neighborhood, your own home,” Kontou says. “We believe that if we want to create nicer neighborhoods that are healthier, more inclusive, but also circular and sustainable, that it really starts by this kind of process.”

Courtesy of Space&Matter

Courtesy of Space&Matter

Courtesy of Space&Matter