Story at a glance:

- Farrow Partners’ Tye Farrow defines salutogenic design and the connection between built environment and health.

- Salutogenesis is a health theory that looks to understand the origins of health and well-being.

Tye Farrow is always learning, always sharing something new and fascinating with anyone who will listen. His career, he says, has been a “real journey of discovery.” As senior partner at Farrow Partners, his current work focuses largely on how the built environment can give or cause health.

Farrow is the first Canadian architect to earn a master’s in Neuroscience Applied to Architecture and Design from the University of Venice. He has been internationally recognized for creating seminal places where people can thrive, and he continues to push the industry to think differently, to open their minds about the possibilities of built environments.

In March 2025 the Toronto-based architect shared his thoughts on the issues as part of a Biophilic Leadership Summit at Serenbe, just outside of Atlanta. “Our physical environments actually change the wiring of our brains, change our bodies, change our physiology, sometimes positive and sometimes negative, as a result of the environments,” he told a packed room of sustainability-minded people.

I caught up with him this summer to learn more about what this meant.

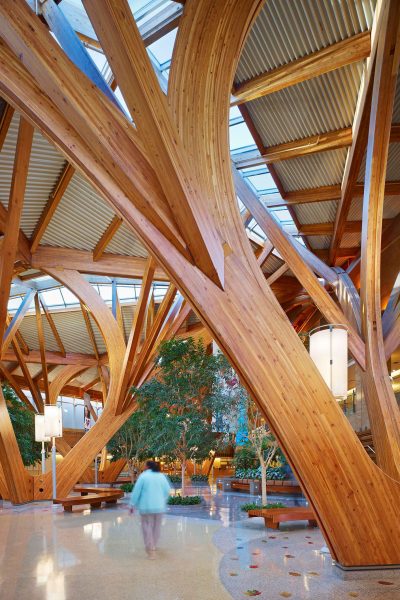

- Credit Valley Hospital in Mississauga, Ontario, includes a new entrance that takes the form of an internal courtyard-like space. Curved wood benches allow you to sit near and under towering wood columns, causing a feeling of familiarity, relaxation, security, and protection. Photo by Tom Arban, courtesy of Farrow Partners

- Architect Tye Farrow speaks at the 2025 Biophilic Leadership Summit at Serenbe. Photo by Foster branding, courtesy of Biophilic Leadership Summit

“It’s not what architecture is but what it does and its ability to act as a non-invasive therapeutic treatment,” he says. “Space can be a nutrient; it can feed you in the same way that our bodies need good quality air, water, food, exercise, social relationships, and sleep.”

What he’s talking about is called salutogenesis—defined in part by Merriam-Webster dictionary as “an approach to human health that examines the factors contributing to the promotion and maintenance of physical and mental well-being rather than disease.”

Coined in the 1970s by Israeli-American professor of medical anthropology Aaron Antonovsky, salutogenesis is, at its core, a health theory that looks to understand the origins of health and well-being.

“How can we actively infuse and use placemaking as an asset-based view as opposed to a deficit-based view?” Farrow asks.

He says those working in and around the built environment need to find a new path forward—one where placemaking is thought of as a health-generating system with the ability to improve well-being as a result of choices made. “We need to start looking at placemaking in architecture not by what it is but fundamentally by what it does,” he says.

Farrow says most people know now how “environmental determinants of health”—air, water, soil—affect us, dating back to the phrase coined in the 1970s. Next, he says, came the idea of “social determinants of health,” looking at social relationships and communities and their impact on health. Then came the idea of economic determinants of health, he says, meaning that if you had a bad job that could cause bad health, too.

Rising 21 feet, feature arches inside the Lauremont School Bayview Campus provide an opportunity for direct contact to the materiality of the structure. Photo by Tom Arban, courtesy of Farrow Partners

“Curiously a lot of those are focused for the most part on stopping bad things from happening. They all touch a little bit on placemaking and the built environment, but what we’re working on right now is something we’ve called the architectural determinants of health.”

Using a salutogenic lens, Farrow and other experts are exploring how the built environment can truly be a nutrient for our health and well-being.

Projects like Credit Valley Hospital in Mississauga, Ontario, were designed to give a sense both of discovery and possibility as well as familiarity and security. Curved wood benches invite you to sit near and under the large wood columns, while other areas are more open and expanding. As beams expand upwards, Farrow Architects describe the design as appearing to push the solid portions of the ceiling upward, giving the sensation that the structure is naturally growing and pushing up, expanding, splitting the roof and exposing the sky beyond. Hopeful sunlight creates patterns on the columns and floor.

At Lauremont School Bayview Campus in Richmond Hill, Ontario, Farrow Partners designed a large addition with glue-laminated timber arches along the arc of a semicircular plan. A skylight and triangular windows punching through the south facade allow light to stream into the space all day, while shadows cast by the timber structure provide interest and change throughout the day, filling the space with life.

“If there’s only one thing you remember, there is no such thing as neutral space,” Farrow says. “There’s no space that doesn’t have an effect on our biology, physiology, and psychology.”

Farrow’s book Constructing Health: How the Built Environment Enhances Your Mind’s Health, published in 2024, dives deeper into the gap in knowledge between the therapeutic medical world and the design community to reveal how the intentional shaping of our environment can support physical and neurological well-being.