Story at a glance:

- Architect Jason McLennan shares his experience designing a deep green house on Bainbridge Island.

- All of the materials in the house were vetted for Red List compliance to ensure a healthy interior.

- The house also used FSC wood and rammed earth construction.

Nestled within a beautiful forest glade on Bainbridge Island, Washington (an island a short ferry ride from Seattle) sits Silver Rock—a modest, humble, poetically enchanting home dedicated to a family’s personal values of peace, serenity, and environmental stewardship.

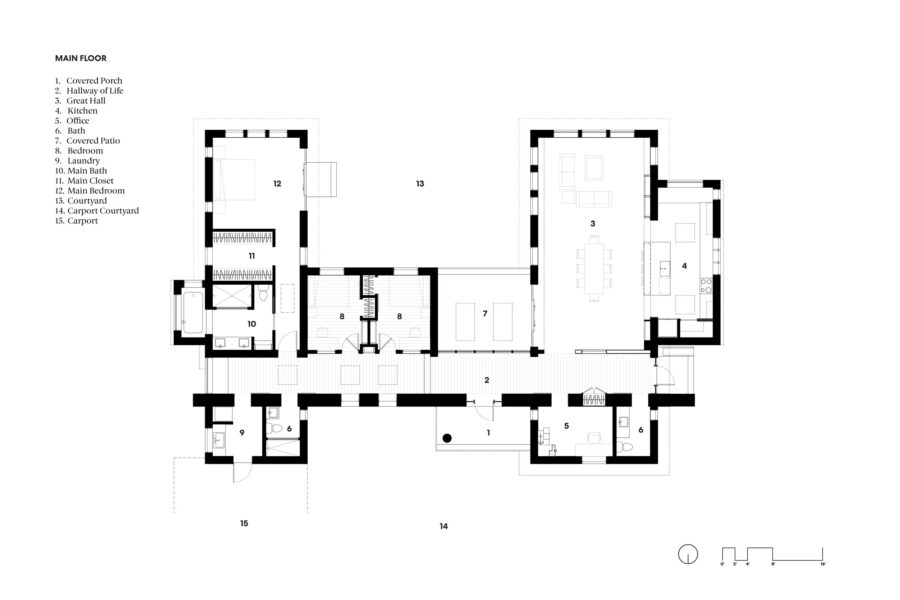

I designed the house for a family of four—two working professionals and their two young children—who value their privacy and wanted a homesite that would connect them to nature and all that it provides. The three-bedroom home is simple in its conception, located in the far northeast corner of their property to have the best solar exposure and to preserve as many large, mature trees on the site. All of the major spaces look out to the south for warmth and views, and the home was designed to frame two courtyards—an entry courtyard for vehicles on the north side of the home and a garden courtyard on the south side of the home.

Inside the home an east-west corridor organizes all of the spaces and was affectionately nicknamed “the Hallway of Life” during the design process—so called because every major space enters off of this singular wide and gracious hall. On either side of the hallway spaces are organized into primary rooms that have double-height pitched roofs—notably the family great room and the master bedroom suite or secondary spaces that have flat roofs/green roofs like the children’s bedrooms, home office spaces, and garage. The house interior feels connected to the gardens and outdoors, as all primary spaces have windows and views on at least three sides. No matter where you stand inside there is at least one view out to nature. Biophilia was an important consideration to create a home that feels connected to place and life itself.

From Earth

The Silver Rock design invited its owners to live more simply. Photo by Emily Hagopian

The home was built with a palette of natural materials—in many cases literally from the site itself. A major organizing principle within the design—the hallway of life—features a massive two-foot thick rammed earth wall made from soil from the site and nearby quarries. The rammed earth wall utilized SIREWALL technology that features insulation in between two steel-reinforced wall sections, creating an energy-efficient and durable construction that is beautiful and creates a feeling of solidity and permanence.

Complementing the rammed earth construction was the use of extensive wood inside and out from responsibly sourced FSC forests or salvaged sources—including some giant salvaged columns that were repurposed. Even trees from the site that were cut down for the project were milled and used in a variety of ways, including for all of the exterior siding (cedar) and some interior wood (Douglas fir). The effort created a “localist construction” with considerably reduced embodied carbon and habitat impacts compared to most new homes.

The outside of the home features charred shou sugi ban cedar siding to ensure longevity without the use of chemicals, paints, and stains. The house feels natural and part of the landscape as a result of its materials and color palette.

Using plentiful natural materials, some from the site itself, made the construction process the most meaningful in construction lead Brant Moore’s career. “The home has a good soul,” he says.

Living Building Challenge

Trees from the site that were cut down for the project were milled and used in a variety of ways, including for all of the exterior siding (cedar) and some interior wood (Douglas fir). Photo by Emily Hagopian

The home was designed around the principles of the Living Building Challenge and, as such, all of the materials in the house were vetted for Red List compliance to ensure a healthy interior in addition to the use of FSC wood and rammed earth construction.

The home features energy-efficient windows, high levels of insulation, and airtight construction and utilized a heat pump and radiant heating in floors to provide internal comfort with a heat recovery ventilation system. As an all-electric home, no combustion means cooking with induction cooktops and avoiding the traditional family hearth. The project demonstrates that you can have a deep green outcome and prioritize beauty and functionality at the same time.

Solving a Major Site Challenge

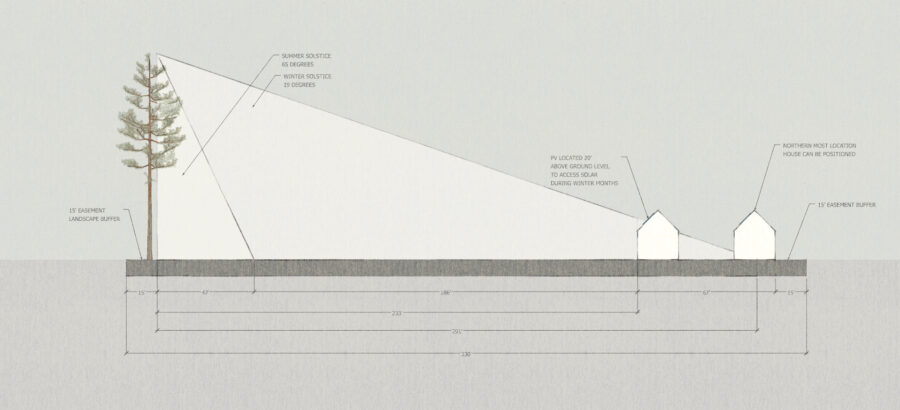

Perhaps the most challenging part of the design process was figuring out where to site the home to meet the project’s many goals—including a balance between solar access for daylight, passive solar gain, energy production, and site preservation.

The project site had an abundance of second growth trees (all of Bainbridge Island had been previously logged at the turn of the previous century), and the tall trees would make having a solar home impossible without proper consideration. As a result the team did extensive solar shading analysis to determine hours of solar exposure at various places on the site to understand year-round availability. The team also looked at the health and age of site trees as well as their suitability for possible reuse for construction materials. The following solutions emerged from the initial site challenges:

Preserve the majority of the site as a nature preserve by locating the house in the corner of the property and creating a future land trust designated area to protect habitat.

Create a small clearing to the south of the home site itself—size determined only by what is needed to ensure solar access or the removal of hazard trees—then use all of the suitable trees from this clearing for building material (reducing off-site habitat impacts).

Orient all major spaces internally and externally to the sun to help during the long, dark Pacific Northwest winters.

Put solar on the garage—the most northeastern portion of the property that gets the most hours of sun year-round.

A Place of Refuge

Photo by Emily Hagopian

Our goal was to design a place of deep beauty and environmental stewardship, but the best judge of that are the clients themselves: “Our house feels like it’s part of the woods around us. The big windows and natural light create a sense of connection to the meadow and the woods. Every time I look at our cabinets, floorboards, or baseboards I remember which trees were cut down to mill those boards … Everything feels deeply connected to the land and the woods here.”

They also told us, “The house has invited us to live more simply. Keeping our furnishings simple, relaxed, and relatable really bolsters that connection to the outdoors—for us and our visitors. It keeps the focus on the ecosystem we live in. Our visitors often say that they don’t want to leave when it’s time to go. ‘It feels so peaceful here’ is a typical refrain.”

As an architect nothing could make me more pleased by the places we strive to create than a testament like this.

Floor 1 of the Silver Rock residence. Drawing courtesy of McLennan Design

Solar shading section diagram. Drawing courtesy of McLennan Design

Project Details

Project: Silver Rock

Location: Bainbridge Island, WA

Size: 3,234 square feet

Architect: McLennan Design

Contractor: Brant Moore with B&L

Photo by Emily Hagopian

Photo by Emily Hagopian