Story at a glance:

- Inclusive design is an approach to design that takes into account the full range of human diversity in order to create products, services, and environments that are as accessible and as usable as possible.

- Inclusive design is closely related to accessible design and universal design but places a higher emphasis on diversity and the creation of one-size-fits-one solutions.

- The Bergami Center for Science, Technology, and Innovation at the University of New Haven demonstrates how inclusive design may be implemented in the AEC Sector.

In an age where thoughtfulness seems largely absent from the technologies, products, and environments we interact with on a daily basis, inclusive design provides a breath of fresh air for everyone involved.

In this article we’ll cover the basics of inclusive design—including what it is, its importance, and how it can be applied in various contexts—as well as take a look at a few examples of how inclusive design can be implemented in the built environment.

What is Inclusive Design?

The Winthrop Public Library was designed using inclusive design principles. Photo by Benjamin Drummond

Inclusive design is a design methodology that takes into account the full range of human diversity with regard to age, gender, language, ability, culture, race, and other identities or forms of human difference. The British Standards Institute defines inclusive design as “the design of mainstream products and/or services that are accessible to, and usable by, as many people as reasonably possible.”

Inclusive design recognizes that it is not always appropriate—and often isn’t possible—to design a single product, service, or environment that addresses the needs of the entire population, thus emphasizing the need for multiple solutions for different groups of people. The Inclusive Design Research Center considers the following three dimensions as being integral to inclusive design:

- Recognize diversity and uniqueness. Inclusive design must keep the diversity and uniqueness of each individual in mind as opposed to smoothing over differences or attempting to enforce a uniform, mass solution; suggests that the best method for achieving inclusive design is to integrate flexible one-size-fits-one configurations that allow for personalization and self-determination.

- Inclusive process and tools. Recognizes that inclusive design teams should be as diverse as possible and include those persons the product, service, or environment is being designed for to facilitate equitable participation; effective inclusive design also necessitates that design and development tools be as usable and accessible as possible.

- Broader beneficial impact. Inclusive designers have a responsibility to be aware of the context and broader impact of their designs and strive to achieve a beneficial impact beyond the intended beneficiaries of the design; requires inclusive design be integrated into design in general.

In practice inclusive design is most often applied to technologies and user interfaces—i.e. things that can be easily adapted and updated over time to reflect the ever-changing spectrum of human experiences—but can in theory be applied across a range of contexts, with architecture being one of them.

Inclusive vs. Accessible vs. Universal Design

Park Avenue Green is fully accessible; 5% of the units are handicap accessible, and the rest are adaptable. Photo by John Bartlestone Photography

Inclusive design is often used interchangeably with accessible and universal design, two other design philosophies that aim to break down barriers between humans and technology. Despite their common goals, however, each ultimately represents a distinct approach to design:

- Inclusive design. Looks to create products, services, and environments that understand and enable people of all demographic backgrounds and abilities.

- Accessible design. Is concerned exclusively with making buildings, interfaces, and other technologies usable to people with disabilities (including physical, visual, auditory, and cognitive disabilities); accessible design has a narrower scope than inclusive design as it is focused on ensuring specific accommodations are met.

- Universal design. Aims to create a single design solution that may be accessed and used by as many people as possible, without need for adaptations or specialized design strategies; universal design has its origins in architecture and is best suited to buildings and other tangible or environmental contexts.

All three types of design can, and often do, overlap with one another, especially when it comes to inclusive and universal design in the built environment. From a technical standpoint, however, each type of design should be regarded as fundamentally separate from the others.

Applications for Inclusive Design

Inclusive design can be implemented in the creation of digital interfaces, consumer products, and built environments. Photo by Peter Aaron/OTTO

Inclusive design can be implemented across a range of contexts, with the most common being technology/interfaces, consumer products/services, and architecture/environments.

Technology & Interfaces

Inclusive design is often easiest to implement when designing or adapting technologies and user interfaces (UI), as the inherently digital nature of these things makes them incredibly adaptable and customizable.

Microsoft’s approach to inclusive design, for example, is based on three basic principles:

- Recognize exclusion. Accept that all persons have their own internal biases and recognize that designing without confronting these biases often results in exclusion of certain groups; user research and testing can be valuable tools when it comes to revealing potential points of exclusion.

- Learn from diversity. Place people at the center of the inclusive design process and involve as many different perspectives as possible to ensure a diversity of ideas, experiences, and concerns.

- Solve for one, extend to many. Each person has their own unique set of abilities and limitations, but designing products for people with chronic or permanent disabilities ultimately creates solutions that benefit all users.

One of the more common examples of inclusive interface design is the addition of a “dark mode” option to websites and apps, in which white or light-colored backgrounds are changed to black and black text becomes white. Such an option is extremely beneficial for seniors and other persons who may have difficulty processing light-colored interfaces—either due to cataracts, light sensitivity, or other vision issues—but many other users find the feature useful in relieving eye strain or for browsing during low-light conditions as well.

Consumer Products

When it comes to consumer products, inclusive design overlaps considerably with accessible design. Rather than develop one-size-fits-all products, the Inclusive Design Toolkit suggests using inclusive design to:

- Create families of products and product derivatives to provide solutions to the best possible coverage of the population.

- Ensure that all products have clear and distinct target users.

- Reduce the level of ability required to use each product so as to improve the user experience for a varied range of customers, across a broad array of situations.

One such example of inclusive design in non-digital consumer products is Singaporean clothing brand Will & Well’s Adaptable collection of clothes featuring alternatives to buttons, back zips, hook-and-eye closures, armholes, and other traditional clothing elements. Though it is designed to make it easier for people with disabilities or restricted mobility to dress themselves, the Adaptable collection is not marketed as a disability-only clothing line, as everyone can benefit from ease in dressing.

Architecture & the Built Environment

While universal design is often the more practical approach when designing buildings and other spaces in the built environment, inclusive design still has its place in the AEC sector. In 2006 the UK Design Council’s Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment (CABE) developed the following set of inclusive design principles:

- Encourage Involvement. The best way to create an inclusive built environment is to involve people from all walks of life in the planning and design phases in order to ensure that the end product is truly representative of the people using it.

- Acknowledge Diversity. Inclusive design recognizes, acknowledges, and celebrates the diversity of people to a greater extent than either accessible or universal design. It is this recognition of diversity that makes inclusive design successful, as it helps uncover different perspectives and reduces the likelihood of any one bias or assumption influencing design decisions.

- Provide Choices. In situations where a single design solution is incapable of meeting the needs of all users, inclusive design provides choices—not as afterthoughts or small concessions, but as thoughtful, intentional options built into the fabric of the space itself.

- Incorporate Flexibility. Another key characteristic of inclusive spaces is flexibility—that is, they are designed to be capable of adapting to changing uses, needs, and demands over time; by designing for flexibility at the outset, inclusive buildings are also more likely to remain operational following changes in ownership, demographics, or functionality rather than succumb to obsolescence.

- Design for Convenience. Finally, inclusive design isn’t just about designing spaces that everyone can use or navigate, but creating spaces that are also convenient and enjoyable for everyone to use and navigate.

How to Implement Inclusive Design in the Built Environment

While there is no single way to effectively implement inclusive design in the built environment, the USGBC’s LEED green building rating system does outline a few key strategies in its Inclusive Design pilot credit.

Inclusive Design Process

During the early planning stages for the new Winthrop Library, Johnston Architects worked with the Friends of Winthrop Library to collect hundreds of comments, suggestions, and concerns from the community. Photo by Benjamin Drummond

One of the most effective ways of implementing inclusive design in any project is to involve the target community or future occupants in the pre-planning and planning stages from the start. In this manner inclusive design becomes a participatory affair, one that requires listening to the wants, needs, and concerns of those who’ll actually be using the space. Gail Shillingford, principal of planning and landscape at B+H Architects, expands on this notion.

“It’s about telling our stories,” Shillingford told gb&d in a previous interview. “I’ve had the pleasure of working with many Indigenous people throughout my career, and one of the things many of them have strongly believed in is that the only way you can create an inclusive environment is to engage and to listen to others’ stories so you can gain an understanding. Without that we are designing for clients, or our egos, but not people.”

Physical Access

LEED also emphasizes the need for maximizing the physical accessibility of a space, encouraging architects to go beyond Federal, state, and local regulatory requirements for both exterior and interior accessibility.

Exterior inclusive design features that help promote physical access include:

- Open sight lines to and from entries as well as public access points

- Easily accessible bike racks, drinking fountains, and assistance animal areas

- Routes, walkways, and paths that are at least 43 inches in width

- Resting areas that include seating options of different heights

- Ramps and curb cuts

- Tactile pavement

Interiors, on the other hand, can be made more accessible by:

- Installing lit screens and monitors with no-glare surfaces

- Equipping elevators with clearly-identifiable, manual features to delay door closing

- Increasing the size of turning spaces to at least 72 inches in diameter

- Providing circulation paths that are at least 20% wider than required

- Installing 36-inch wide doors at minimum, in all occupied spaces

Wayfinding

The stainless steel roof of this airport forms stretch over column-free structures to create dramatic, expansive interior spaces that form a rationalized programmatic layout of passenger circulation and amenities in order to improve wayfinding and level of service. Photo by Nick Merrick

Of course, it’s not enough for a space to just be accessible. Visitors must also be able to navigate a space, regardless of their physical, cognitive, or language ability. For that reason adding a variety of easily-understood wayfinding features is integral to the creation of an inclusive built environment.

Possible wayfinding features include:

- Audio and tactile maps to guide blind/low-vision people

- Continuous linear path indicators

- Color blocking and patterns to identify key public access spaces

- Directional signage that use symbols or other non-text diagrams, Braille, and active audio/visual signaling on dynamic signs

Assistive Technology

To ensure that a building’s intended functions can be used by all visitors, it may be necessary to include assistive technology, or technology that is designed to maintain, increase, or otherwise improve functionality for children, the elderly, those with disabilities, or neurodiverse persons. Some of the more common examples of assistive technology include height-adjustable desks and counters, touch-screen or voice operated controls, handles and doorknobs that do not require grasping or twisting, assistive keyboards, magnifiers, eye tracking, and more.

Emotional Health

RiverSouth in Austin features a green roof that both keeps the building cool and gives people a place to escape. Photo by Casey Dunn

As global rates of depression, anxiety, and other mental health conditions continue to rise, it’s important for buildings to positively impact the psyche and nurture occupants’ emotional health. This facet of inclusive design is heavily linked to biophilic design—or design that fosters a connection between people and the natural world—as features like plants, views of nature, natural sunlight, running water, passive ventilation, and nature-inspired art are all known to help improve mood and reduce feelings of stress.

Inclusive Spaces

Another hallmark of inclusive design in the built environment is the addition of spaces designed with a certain demographic or demographics in mind. Some examples of inclusive spaces—like quiet/meditation/prayer rooms and public restrooms—have become relatively commonplace in recent years, whereas spaces like lactation rooms for new mothers, all-gender restrooms, and accessible fitness areas are still considered novel additions.

Employee Training

Lastly, LEED stresses the importance of providing inclusive design training for all building operations and management employees or developing an operations and management guidebook that is applicable to all visitors and occupants. Suggested topics include:

- Guidance for welcoming visitors/customers and working with staff with sensory, accessibility, or cognitive challenges

- List of Federal and state/local protected classes

- Nondiscrimination policies and procedures

- Overview of any and all applicable laws, codes, and organizational non-discrimination/labor equality policies

3 Examples of Inclusive Design in Architecture

Now that we’ve a better understanding of inclusive design and its principles, let’s take a look at a few architectural projects that have consciously incorporated inclusivity into their designs.

1. Schoenecker Center for STEAM Education, St. Paul, MN

The new Schoenecker Center for STEAM Education at the University of St. Thomas was designed by BWBR in collaboration with Robert A.M. Stern Architects (RAMSA) with inclusivity as one of its guiding principles. Rendering courtesy of BWBR and RAMSA

Designed by BWBR in collaboration with Robert A.M. Stern Architects for the University of St. Thomas, the Schoenecker Center for STEAM Education is a masterclass in how inclusive design may be implemented in higher education settings.

During the early phases of the planning process, BWBR—with help from the university’s office of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion—met with stakeholder focus groups composed of students, alumni, and other members of the university community to field ideas and discuss potential points of concern for the new building. Using the information gathered during these meetings and the LEED Inclusive Design pilot credits, the team set out to design a space that was welcoming and representative of all.

“To accomplish this we prioritized creating inclusive spaces like all-gender restrooms, lactation rooms, public education areas, and spaces that encourage frequent, casual interaction to reduce the probability of social isolation,” Stephanie McDaniel, president and CEO of BWBR, told gb&d in a previous interview. “We also incorporated assistive technology like accessible height service counters and height adjustable furniture, as well as wayfinding tools like non-text diagrams, braille, and patterns and color-blocking to identify key public spaces.”

Encompassing 130,000 square feet, the completed Schoenecker Center for STEAM Education includes flexible and collaborative workspaces; a two-story engineering bay; labs for biology, chemistry, physics, and robotics; a music rehearsal space; art gallery, atrium, cafeteria, and emerging media program complete with studios and newsrooms.

2. Winthrop Public Library, Winthrop, WA

Johnston Architects and Prentiss Balance Wickline Architects involved the community in the planning stages of the Winthrop Public Library to ensure it was representative of their needs. Photo by Benjamin Drummond

Having long been underserved by a small library with poor access to essential services and multimedia resources, Winthrop—a small town in the heart of Washington’s Methow Valley—was in dire need of a library capable of meeting the community’s education, entertainment, and general enrichment needs.

With help from Prentiss Balance Wickline Architects and Friends of the Winthrop Library, Johnston Architects was able to come up with a solution. Hundreds of comments and requests were collected as a part of the firm’s Hopes & Dreams charrette process and used to design a library that fulfilled the community’s goals and addressed those aspects that simply weren’t working.

“We designed the building with an open floor plan to be flexible and continuously adapt its space layout to the evolving needs for programmed activity,” Harmony Cooper, former project architect at Johnston Architects, told gb&d in a previous interview. “Spaces range from intimate reading window seats and quiet study areas to more active teen and children’s areas, flexible meeting halls that can be subdivided, a main stack space where larger events can also happen, and a maker space that is fit for 3D printing and digital fabrication.”

The completed Winthrop Public Library is capable of holding a collection of more than 20,000 materials and houses a large community room available after hours for events, meetings, and other programming.

3. Bergami Center, West Haven, CT

Stakeholder groups consisting of deans, professors, administration faculty, and other university representatives were consulted during the early planning stages of the Bergami Center. Photo by Peter Aaron/OTTO

When the University of New Haven (UNH) concluded in 2018 that a new academic building was needed to support campus growth, they weren’t entirely sure what kind of building would be most beneficial—so UNH, with the help of New Haven-based architectural firm Svigals + Partners, turned to the university’s stakeholder community for ideas.

“We had a stakeholder group composed of the deans of each of the schools, professors, administration, the design team—a little bit of everyone from campus,” Katelyn Chapin, associate at Svigals + Partners, told gb&d in a previous interview. “We brainstormed what types of spaces would be required for their campus. Being a community-oriented person, this was my favorite part of the process.”

The end result was the Bergami Center for Science, Technology, and Innovation, an interdisciplinary hub dedicated to learning, co-creation, and the betterment of society. Intended as a space where students of all majors could come to learn, create, and collaborate, the Bergami Center encompasses science classrooms, technology-supported “smart” classrooms, multimedia production studios, a makerspace, as well as an atrium and café.

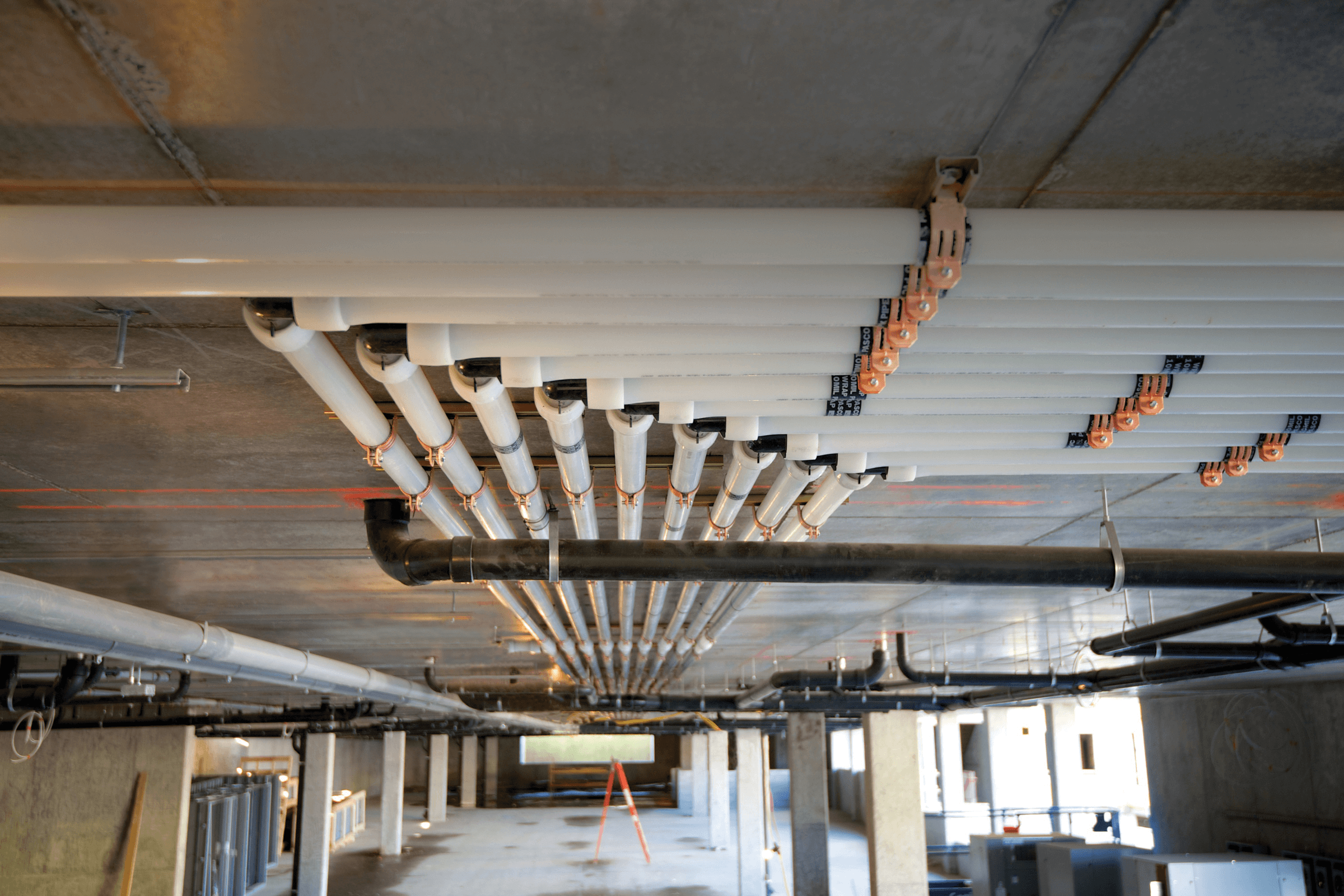

From a sustainability standpoint the center features copious daylighting strategies, low-flow fixtures, high-efficiency boilers and chillers, on-demand controlled ventilation, exterior sun shades, and was partially constructed from recycled materials—all of which helped it earn LEED Gold certification.