Story at a glance:

- At the onset of World War II in 1939, the Bata family fled Czechoslovakia and founded the Bata Shoe Factory in Batawa, Canada in Ontario.

- The adaptive reuse project transformed the former manufacturing facility into a mixed-use residential, commercial, and community building.

- Sustainable features include thermal windows, eco-friendly building materials, geothermal energy, and near zero carbon dioxide emissions.

In the quiet town of Batawa, Canada, located around 100 miles east of Toronto, the Bata Shoe Factory’s adaptive reuse is more than just a renovation. Designed by BDP Quadrangle in collaboration with Dubbeldam Architecture + Design, the award-winning, mixed-use building embraces the town’s history and upholds the founders’ vision for sustainable development.

Batawa was founded in 1939 when Tomáš Bata uprooted the Bata shoe empire from Czechoslovakia to Canada. More than 100 workers and their families relocated with the company, including Bata’s future wife, Sonja. By 1989 the factory employed nearly 1,500 people and rejuvenated the local community with its in-house schools, churches, and sports facilities.

The factory was sold to a plastics company in 2000, but Sonja Bata repurchased the 1,500-acre site in 2008 with plans to repurpose it as a model for social and environmental sustainability. Sonja Bata passed away shortly before the project’s completion in 2019, but the revitalized Bata Shoe Factory is the result of her ambitious vision.

“Mrs. Sonja Bata was a visionary with a passion for architecture and design,” says Dev Mehta, senior associate at BDP Quadrangle. “We worked very closely with Mrs. Bata on every aspect of the design, poring over details, and often spending several consecutive meetings discussing them. It was such an energetic and passionate process where every design decision was questioned in the pursuit of design excellence.”

Mixed-Use Design

Bata Shoe Factory’s 47 residential units include 12-foot high ceilings and ample natural light. Photo by Nanne Springer

The modern five-story building features 47 residential units on the upper three floors. The units vary in size and layout to provide affordable and flexible options to individuals and families.

The new building retains its original concrete waffle slab structure—an innovation that the Batas brought with them from Europe—which allows for spacious residential units with 12-foot high ceilings and abundant natural light.

Similar to the former factory’s community-based design philosophy, the renovated mixed-use building acts as a community hub for residents and non-residents alike. The ground and second floors provide ample retail, commercial, and community spaces. These amenities include a children’s daycare with an outdoor playground, educational incubators, leasable spaces for local businesses, and a rooftop terrace with panoramic views.

Dynamic Exterior Facade

The five-story building features 47 residential units on the upper three floors with retail, commercial, and community amenities below. Photo by Scott Norsworthy

The building’s exterior facade features repeated structural bays with glazing and brick cladding that resemble the factory’s original appearance. Cantilevered balconies extend past the facade, which significantly reduces thermal bridging, Mehta says.

The wood cladding on the soffits and balcony walls softens the industrial appearance and creates harmony with its surroundings. Below the projecting center volume is a wide entrance canopy with dramatic LED lighting and the same wood paneling used throughout the building.

Industrial Modernist Interiors

In the lobby, a geometric, sculptural steel staircase wraps around an original concrete column from the former manufacturing factory. Photo by Scott Norsworthy

The industrial modernist design works in tandem with the building’s historic roots to create sleek and refined interior spaces. In the lobby, speckled white terrazzo floors contrast the rich wood panels. Above the sitting area, a large light fixture is a focal piece of the airy, welcoming environment.

A geometric, sculptural steel staircase wraps around an exposed concrete column; a nod to the factory’s original foundation. These columns are one of many restored features from the former manufacturing facility.

Green Energy

The large entrance canopy welcomes guests with dramatic LED lights and sophisticated wood paneling. Photo by Scott Norsworthy

In alignment with Sonja Bata’s vision to advance sustainable architecture, the facility also preserved its overall concrete structure and saved much of the building’s embodied carbon footprint in the process.

“Approximately 80% of a building’s embodied carbon can be found in its structural components, and we estimated that the retention of the building’s slabs, beams, and columns represented a savings of approximately 2 million kg of carbon dioxide emissions and roughly 900 cement truck deliveries,” says Heather Dubbeldam, principal of Dubbeldam Architecture + Design.

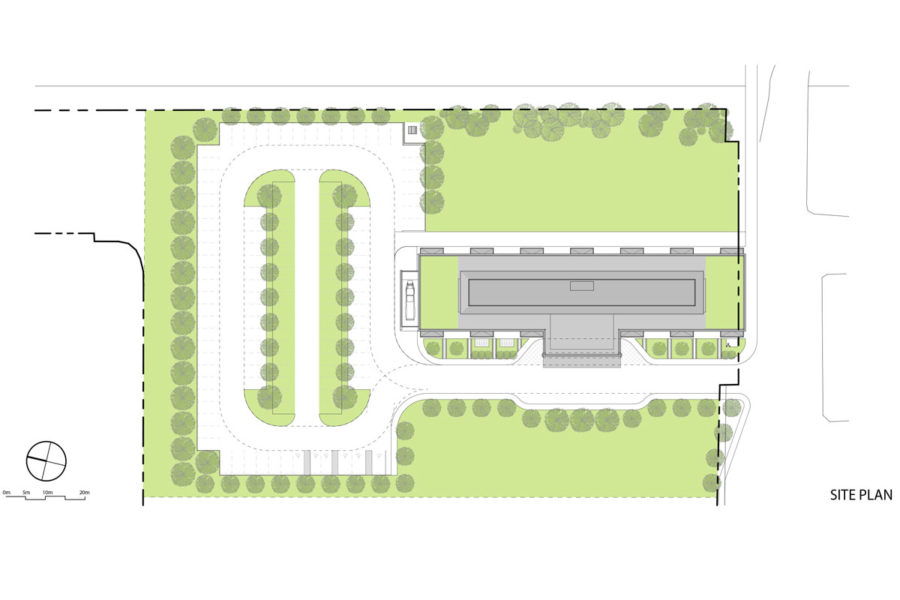

Since no natural gas is used in the building, the project’s operating carbon dioxide emissions are near zero. Geothermal energy—produced from a field of 63 boreholes below the parking lot—supplies 100% of the building’s HVAC needs.

Sustainable Building Materials

The project’s new sustainable materials like brick masonry, steel, glass, and warm wood accents fuse the building’s modernist heritage with contemporary design. Photo by Scott Norsworthy

From eco-friendly building materials to geothermal energy, sustainability is integral to the project. The interior and exterior building materials were carefully chosen for their durability and sustainable characteristics. The use of new materials like brick masonry, steel, glass, and warm wood accents fuses the building’s modernist heritage with contemporary design.

The Parklex panels used for the interior and exterior wood finishes are EPD- and FSC-certified, and the energy Parklex uses to fabricate the panels comes from a 100% renewable source. Also, the carpet tiles were made from recycled fishing nets, and the “millwork for the kitchens and bathrooms have low formaldehyde materials to ensure better air quality and occupant health,” says Dubbeldam.

To seamlessly blend the project’s key characteristics—history, sustainability, and community—every design decision required extensive consideration. The architectural team 3D-printed custom handrail profiles for the balcony guards to understand how it would feel in one’s hands. Even the palette of selected materials has a symbolic meaning: a direct reference to the building’s modernist roots tracing back to the Czech factory town of Zlin.

“The design process was not straightforward or simple, nor should it have been given the complexity of what we were trying to achieve. However, a successful project should make it appear like it was—and we believe this was ultimately achieved,” Mehta says.

Courtesy of BDP Quadrangle and Dubbeldam Architecture + Design

Courtesy of BDP Quadrangle and Dubbeldam Architecture + Design